Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Joseph Borelli

All rights reserved

E-Book year 2020

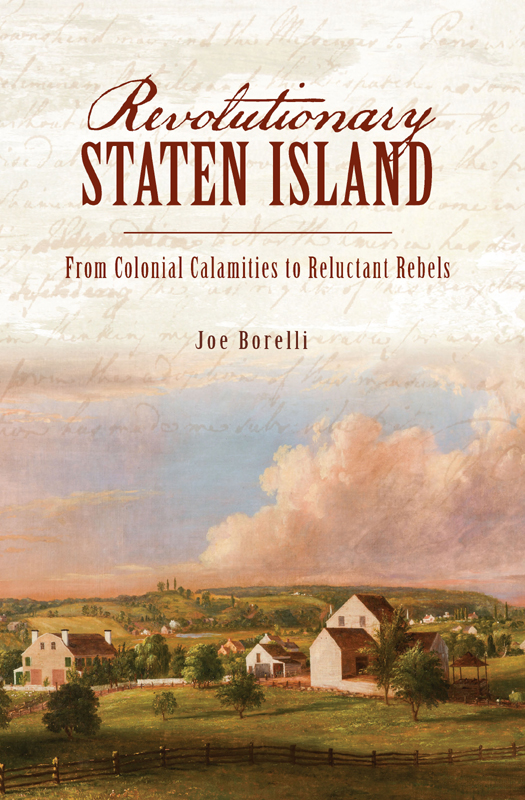

Front cover: Jasper Cropseys Cortelyou Farm gives a glimpse of what the South Shore looked like in early America. Staten Island Historical Society.

First published 2020

ISBN 978.1.4396.7104.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020938466

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.4671.4762.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

INTRODUCTION

Once upon a time there was an island of incomparable beauty called Aquahonga.

Nearly 125 years ago, as Richmond County stood on the precipice of its consolidation with the other four boroughs, an unknown author published a short article in the New York Sun titled Aquahonga, which is believed to be the Native American name for Staten Island. In the article, he described how the scenic and tranquil island would surely be lost, eventually to become the new Bowery of Greater New York. He ended with the line: It will be a very many long years before a historian can tell a story beginning with the words: Once upon a time there was an island of incomparable beauty called Aquahonga.

Today, his prophecy is realized, and like him, I hope this book helps paint a picture of what this county was before it joined in the experiment called the City of Greater New York. For centuries, it was independent and had a unique historical relevance in its own right. Although we have not yet become the Bowery, this is the story of an island of incomparable beauty when it was a unique part of Americas colonial experience and war for liberty.

Most islanders take for granted that it was the boroughs twentieth-century history that shaped its modern footing, and in large part theyre right. Politicians of that era are responsible for giving Staten Island its current building stock and suburban feel. Postwar Staten Island grew as New Yorks population swelled, automobiles became household commodities, public construction projects were in full swing and middle-class flight to the suburbs was the norm.

That chapter of Staten Islands history is not the focus of this book, nor is it the islands role as a borough of New York City. We look further back to a time when New York City, and the United States itself, did not exist as it does now. Of course, a history of early Richmond could not ignore that it has always been inherently linked to the island of Manhattan. However, for the majority of the countys history, as far back as its earliest settlers, it existed as a separate entity with its own municipalities, subdivisions and partially autonomous government. In fact, some New York historians, like CUNYs George J. Lankevich, have even suggested that modern Staten Islands unique perspective of its place in New York City is a holdover from the Dutch patroon system, when settlers first felt that they suffered under the alien customs of colonial governments in Manhattan.

STATEN ISLANDS HISTORY IS worth remembering. It was one of the first places that European explorers set their eyes on in modern America. It saw some of the earliest contacts with native peoples in 1524. It is one of the oldest settled counties in the country. Its colonial history predates that of the British at Philadelphia and the French in Louisiana. It was populated by successive waves of immigration, beginning in the 1700s with the Dutch and French and continued unbroken to the twentieth century. It was the site of war, misery, progress, prosperity, failure, fear and dense forests.

The first chronicle of the boroughs history was John Jay Clutes Annals of Staten Island, From Its Discovery to the Present Time. The author was a historian and genealogist and, like me, served in public office. He was a collector of antiquities and acquired, in his words, a large amount of interesting materials relating to the history of Staten Island.

Ten years later, another chronicle was published by Richard M. Bayles, titled A History of Richmond County, (Staten Island) New York, from Its Discovery to the Present Time, and in 1898, Ira K. Morris published Morriss History of Staten Island, New York. However, Charles Leng and William T. Davis completed the most comprehensive five-volume history of the county between 1929 and 1933. Staten Island and Its People, A History, 16091929 details the boroughs chronology and adds encyclopedic articles on prominent people, places and institutions. Leng and Davis are also noteworthy as founders of the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences and the Staten Island Historical Society, both still in existence. There is a wildlife sanctuary in Travis and school in St. George bearing Daviss name, and Willowbrook is home to the Charles W. Leng Middle School.

It was through reading Staten Island and Its People that I became interested in the countys past. After receiving my bachelors degree in history from Marist College, I took a part-time job at Casey Funeral Home on Slosson Avenue. One of my easier duties was to man the office late into the night and wait for inevitable phone calls from nursing homes or family members. In between those conversations were hours of quiet solitude as I struggled (often unsuccessfully) to stay awake. The Caseys had been in the business for generations, and luckily for me, they had the rare original prints of the book on a basement bookshelf. Had the iPhone been invented by 2004, I might have never turned the cover. Yet, one hundred pages or so in, I was hooked.

Now, as then, Staten Island deserves an examination of its history, not merely as a part of New York City but also on its own, as just about every scene of Americas story has played out on our shores. Hopefully, this tale of how Staten Island came to be is as interesting and relevant to readers today as it was when Leng and Davis put pen to paper in 1929.

THE COLLISION OF CONTINENTS

As the sun rose on a calm spring day in April 1524, those living on the island of Aquahonga Monocknong began their morning business as any other. At that time of year, the women were at work using shell and wooden hoes to plant beans and corn, while the men hunted throughout the islands wooded hills and set fishing nets along the muddy river that kept it divided from the mainland.

That morning, while peering through the dense trees of the high ridgeline that runs along the islands eastern shore, one of the natives must have noticed a sight never before seen and well beyond what could have ever been imagined. Look! he or she would have shouted in their Algonquian tongue to others in the community.

A boat, grander and more complex than any in their known world, grew larger among the waves as it slowly approached from the southeastern horizon. As it drew near, the natives may have originally mistaken it for a giant waterfowl or sea creature, but soon its vast white sails arrayed among its three masts might have resembled a thick fog amid trees. In all likelihood, the sheer size and intricacies of its wooden decks were larger than any man-made structure that had ever met their eyes.