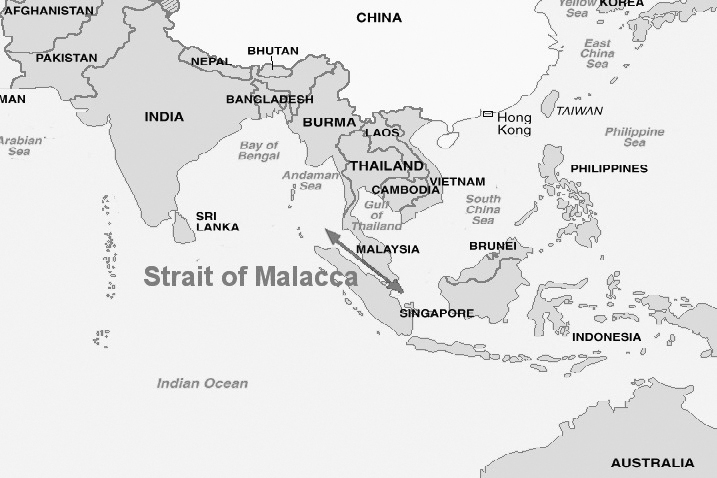

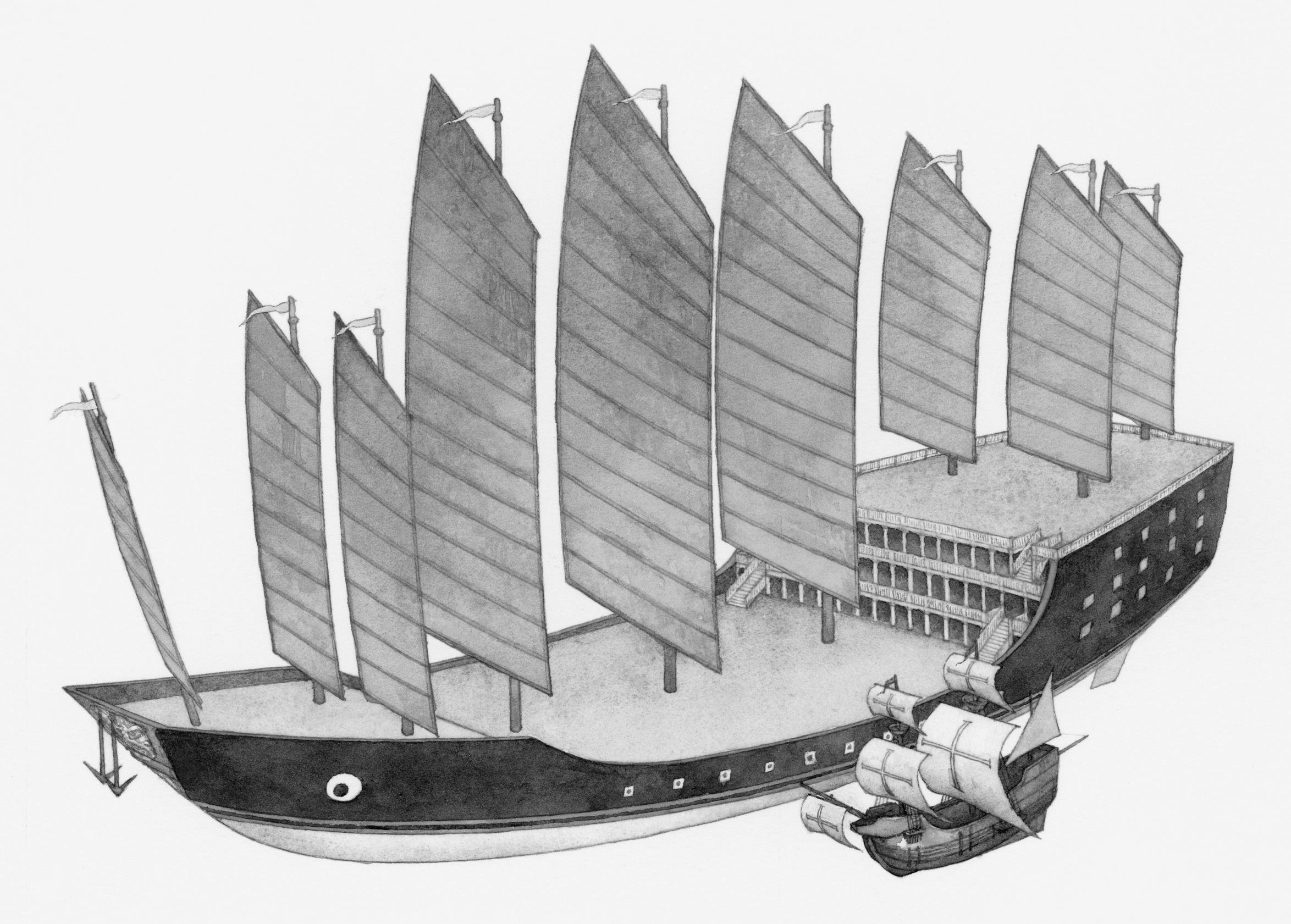

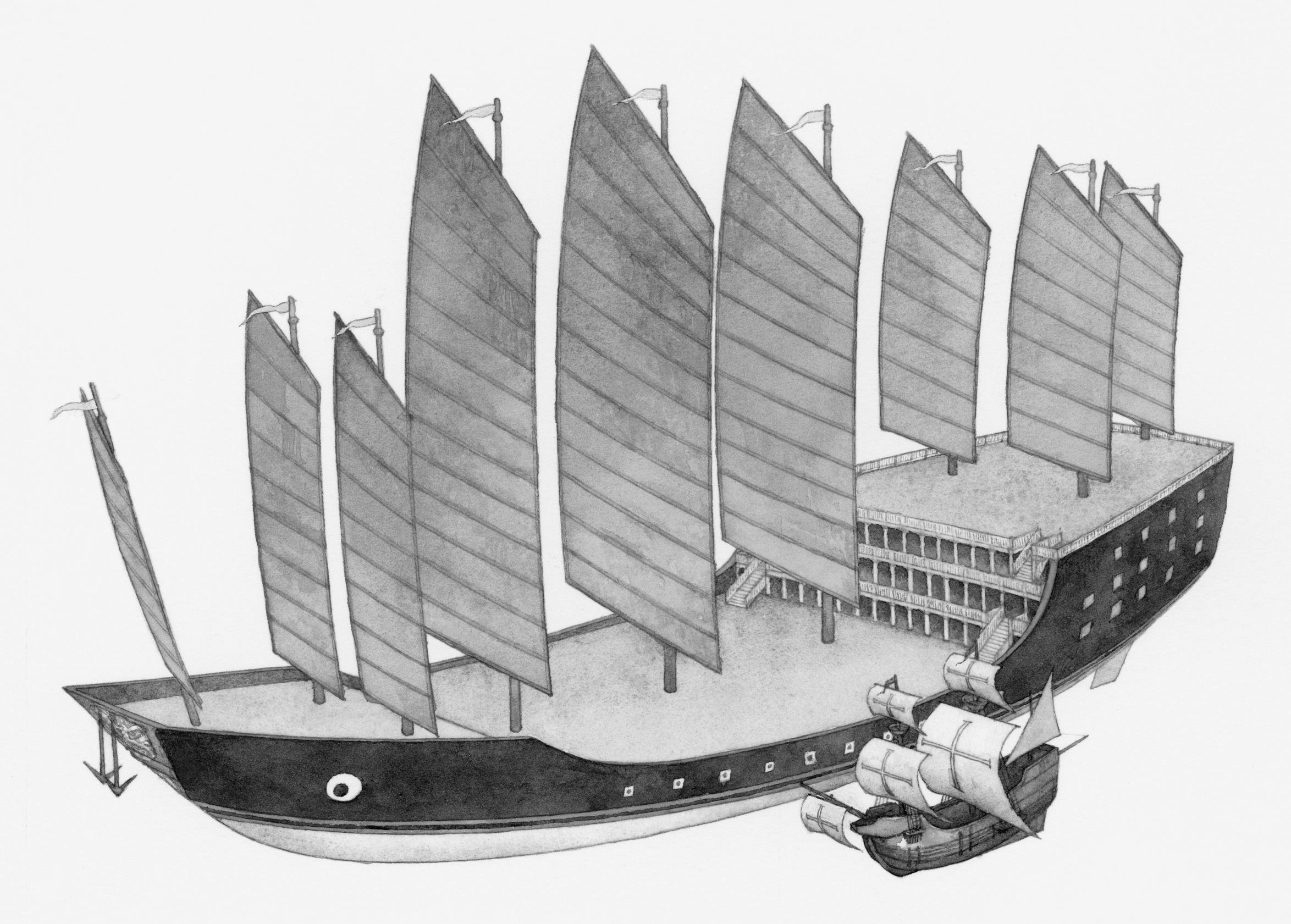

The routes of Chinas Treasure Fleet, 14051433. Side-by-side comparison of one of Zheng Hes treasure ships with a ship from the fleet of Vasco da Gama.

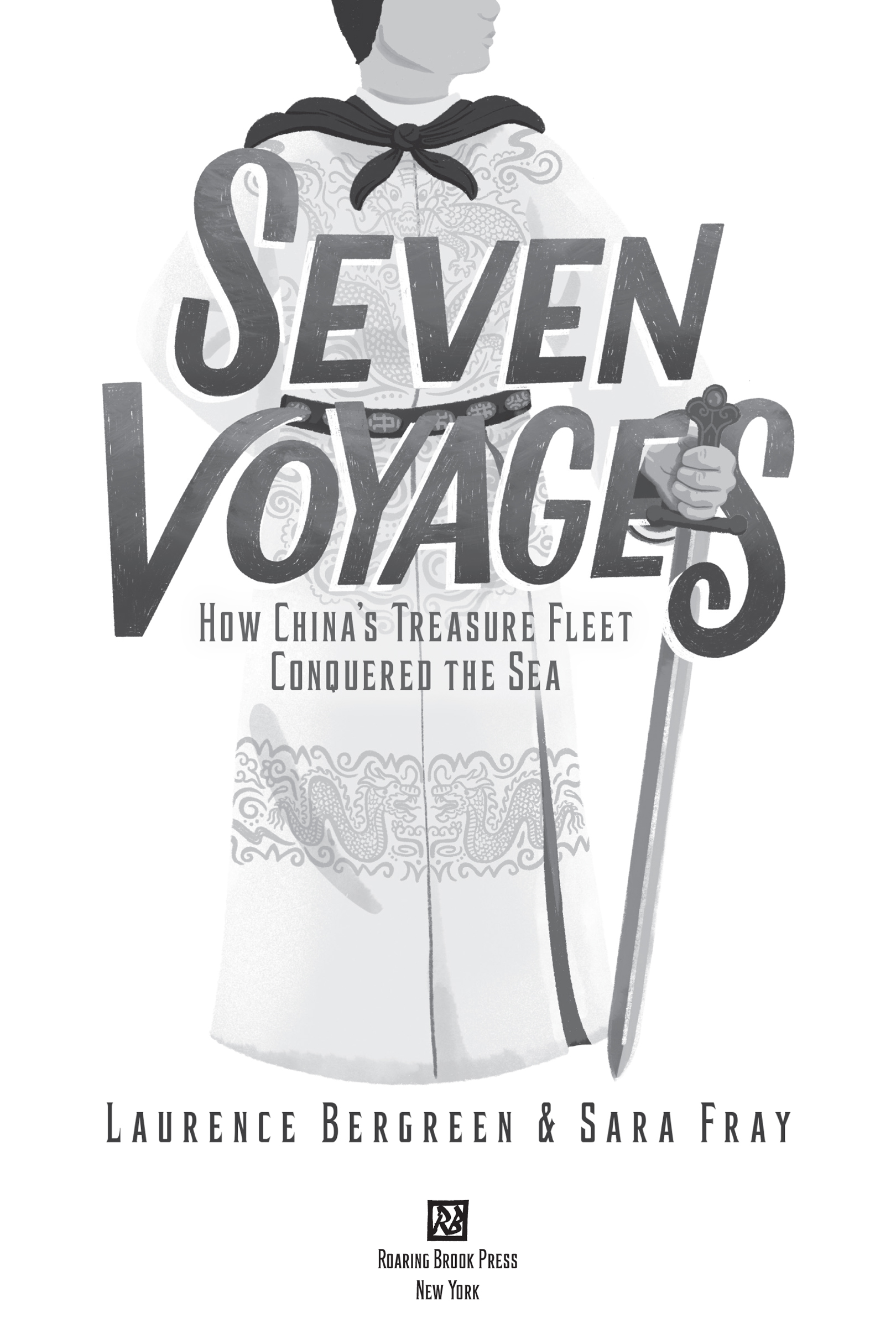

The Strait of Malacca was one of the most vital and hazardous shipping channels in the world. To the west lay the Indian Ocean, to the east, the Pacific, and between them were five hundred miles of dangerous waterway teeming with pirates skilled at pillaging ships carrying all the worlds goodsspices, gems, fragrances, and silk.

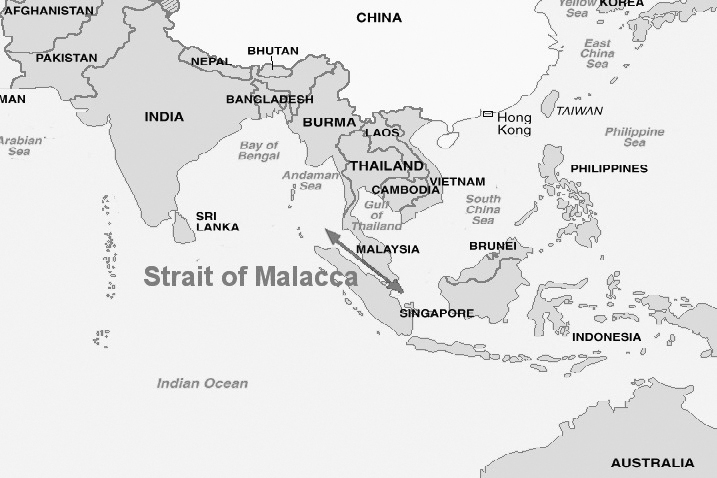

Map of the Strait of Malacca situated between the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra in Western Indonesia.

In the spring of 1407, deep within the dark watery maze of the Strait of Malacca lurked an army of pirates entirely unaware that their reign of tyranny, death, and destruction was about to end at the hands of the seven-foot-tall admiral of the Treasure Fleet, Zheng He.

The emperor of China, Zhu Di, had entrusted Zheng He, his most loyal soldier, with the monumental task of establishing China as the leader of global trade and the ultimate force at sea. Although the admiral preferred peaceful diplomacy to warfare, his fidelity to the emperor drove him to violence. Nothing could stop Zheng He from accomplishing his missionnot even the deadliest, most ruthless army of pirates in the Eastern Hemisphere.

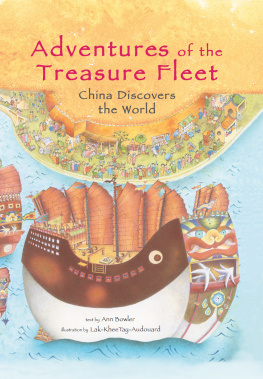

To prepare for battle, Zheng He ordered his fleet to invade the harbor of Palembang in Indonesias South Sumatra province. Three hundred and seventeen colossal wooden ships spreading massive red-silk sails cut through the murky brown waters of the Musi River. Among them, the smaller vessels, called junks, and the heavily armed combat ships began to swarm the shoreline. Behind them sailed sixty-two gigantic treasure ships adorned with menacing dragon eyes. Spectators at the docks, though accustomed to the usual flow of merchant vessels, had never before witnessed ships of such epic proportions and were awestruck and breathless.

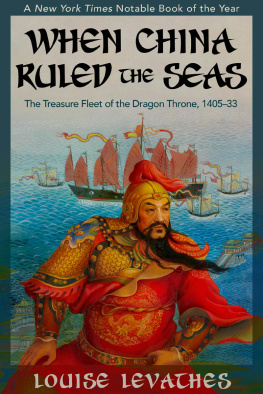

The largest sailboats in the fleet, called treasure ships, were more than 450 feet long, dwarfing anything European explorers would command a full century later. In fact, one treasure ship could fit four of Christopher Columbuss flagships inside it. They were the supertankers of their day and the largest vessels known to traverse the East China Sea or the Pacific Ocean until World War I.

Chinas Treasure Fleet was more than an armada; it was a well-organized, technologically advanced floating city. There were separate vessels for soldiers, giant tanks of drinking water, and a vegetable garden. Even the horses had their own boat. Protecting the fleet were thousands of heavily armed troops ready to pacify anyone in their way, including the most vicious group of pirates imaginable.

An imposing Ming treasure ship all but dwarfs a Portuguese ship.

To secure a future for Chinas trade route, Zheng He would have to overthrow the leader of the pirates. His mission was both imperative and incredibly risky because local pirates were known to plunder anything that passed through the Strait of Malacca. The pirates knew the best hiding spots in the winding waters of the river inlets, and they used their ambushed victims shock to easily board and overwhelm their ships.

The pirate chief, Chen Zuyi, lived like a king. He had amassed an enormous collection of stolen goods, built the largest army of pirates anywhere in the world, and forced the residents of Palembang to obey his violent authority. This created an especially difficult situation for merchants who relied on the citys port to trade for valuable commodities such as black pepper and cinnamon.

As the treasure ships glided toward the Palembang harbor, imperial troops perched at the tops of the soaring masts scanned the surrounding waterways for pirate activity. The harbor was eerily tranquil; there was no sign of Chen Zuyi or his army, only the steady movement of a small fishing vessel approaching the fleet. As luck would have it, the local Chinese merchant aboard that boat, Shi Jinqing, disembarked with a critical secret: Chen Zuyi and his pirates were hiding in nearby waterways, preparing to ambush the treasure ships. When Admiral Zheng He learned of the scheme, he was left with no choice but to prepare for war.

Wasting not a moment, Zheng He devised a foolproof battle plan and ordered his fleet into a strategic formation. The steady, ominous beating of drums on Zheng Hes ships grew louder as flags were raised to signal the ships launch. The largest ships, with their valuable loads of porcelain, silk, and gold, sailed away from the harbor to block all passages running out to the Java Sea. No one would be able to escape under the watchful gaze of the admiral.

Imperial troops in hundreds of smaller warships readied their swords, explosives, and flaming arrows for a brutal offensive. When all the necessary preparations were ready, Zheng He made the first move.

A small flotilla carrying a messenger traveled across the harbor to demand that the pirate chief surrender peacefully or face the consequences. Zheng He had been warned that Chen Zuyis surrender was a ploy, and he anticipated his opponent would feign cooperation.

After a brief delay, Chen Zuyi agreed to Zheng Hes terms and ordered his fleet of murderers, thousands deep, to gather in the harbor.

How small the pirate ships seemed in comparison to the behemoth treasure ships. Even the Ming Chinese combat ships loomed large over the pirate boats.

Finally, Zheng He gave the signal to attack.

Two centuries before the Treasure Fleet was launched, China was the most advanced and populous empire in the world. Major cities in China contained ten times as many people as major European capitals: 750,000 in Chinas cities compared to the typical 75,000 in cities in Europe.

Monumental statue of Zheng He at Zheng He Park, a prominent historical site in the city of Kunming, Yunnan, China.

China fielded the largest army and navy and maintained the largest trading network in the world, extending its influence across Asia, Indonesia, and India. Although Chinas wide reach encompassed half the globe, its maritime prowess was relatively unknown throughout Europe.