First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd

First published in India by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2019

1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot No. 40, SP Infocity, Dr MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096

Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates.

Copyright Bertil Lintner

ISBN: 9789388689717

The views and opinions expressed in this work are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same.

All rights reserved

For sale only within the territories of India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Any circulation of this edition outside these countries is strictly prohibited and unauthorised.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

CONTENTS

A giant monument showing four figures wheeling a circular object between them, their determined faces pointing directly south, stands where the road on the wide, concrete bridge that spans the Ruili River leads into Jiegao, a tiny sliver of Chinese territory on the other side. The Chinese characters on the base of the monument spell out the phrase Unite, Blaze Paths, Forge Ahead!. Or, in more mundane terms: Southeast Asia, here we come!

What is striking about this monument is not so much where it can be found. Jiegao, a roughly hewn two-square-kilometre enclave completely surrounded by Myanmar, is a thriving commercial centre and the gateway to markets across the border and beyond. But the monument was placed there, with remarkable foresight, in 1993 when the bridge had only just been built and Jiegao consisted of little more than paddy fields with a few bamboo huts scattered between them. Today, 25 years later, there are high-rise buildings, luxury hotels, stores offering all kinds of wares, and a huge jade market where buyers from all over China shop for this precious stone, which is found in its imperial green form only in Hpakan, in northernmost Myanmar.

Every morning, caravans of trucks laden with Chinese consumer goods pass through the border post at Jiegao and into Muse on the Myanmar side. They are destined for Lashio, Mandalay, Yangon and other Myanmar cities and towns, and even places as far away as Tamu on Myanmars border with India. From Tamu, the goods are then brought into Moreh in India and from there on to Imphal, Dimapur, Kohima and Guwahati the key cities in Indias northeastern states. Not only Myanmar but also northeastern India is being flooded with cheap Chinese merchandise. For India, the road from Guwahati to Moreh is supposed to be its highway to Southeast Asia and part of what used to be called a Look East, and now designated an Act East, policy. But most of the convoys of lorries head in the opposite direction; it is China, not India, which benefits most from the opening of new trade routes through the state formerly known as Burma.

The trade imbalance is not quite as pronounced as at Jiegao, where huge amounts of jade are imported from Myanmar. But that barely registers compared with the volume of Chinese exports heading in the opposite direction, through the border post. Apart from jade, there is little more than amber, petrified wood, seafood and fruit coming from the Myanmar side. A once thriving timber trade has dwindled to almost nothing since China imposed restrictions and the forests of northern Myanmar are now almost depleted of trees.

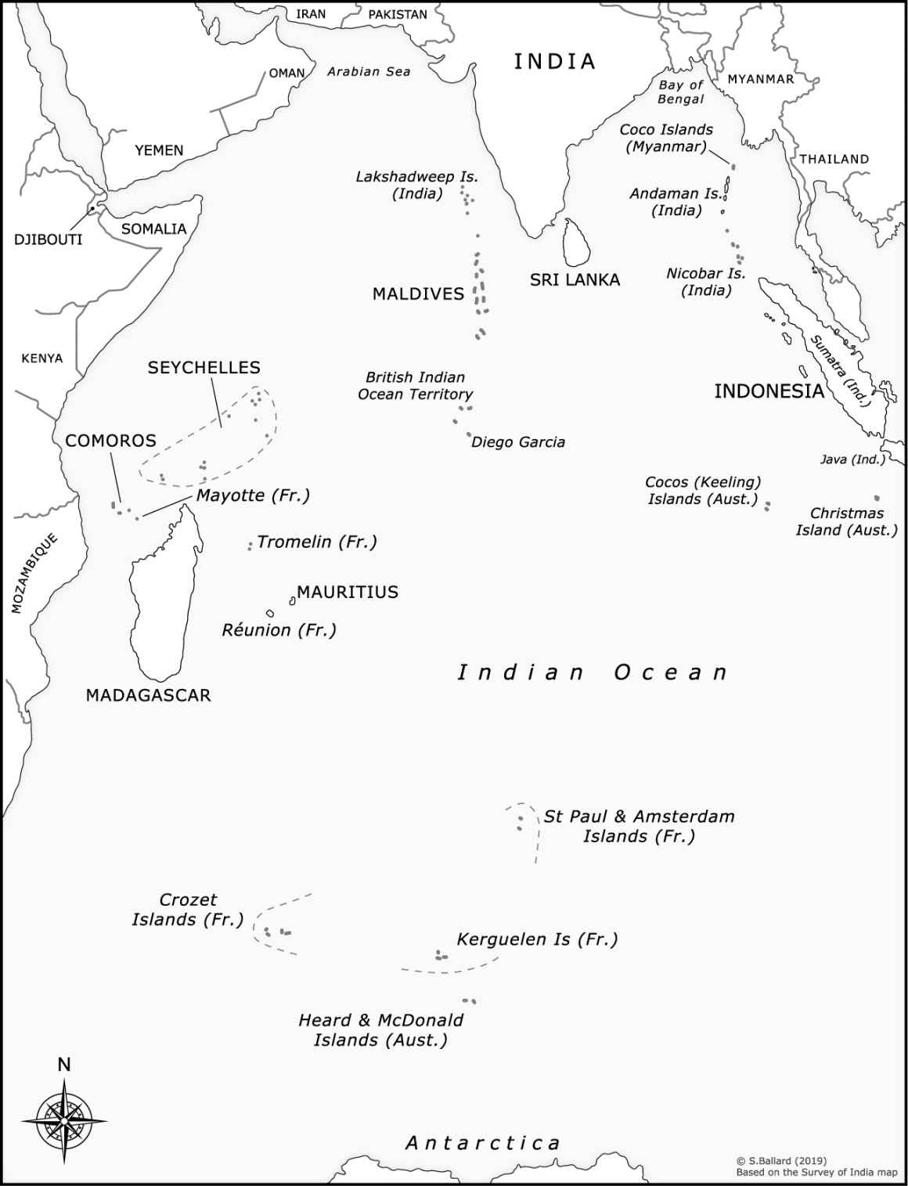

The Jiegao crossing is of utmost importance to the export-oriented economic growth of Chinas landlocked, southwestern provinces. But not far from Ruili are newly laid pipelines through which oil and gas are being transported from the Myanmar coast to Yunnan, bypassing the vulnerable geostrategic choke point of the Malacca Strait. On the coast where the pipelines originate lies the port of Kyaukpyu, the construction of which was announced in 2007 and which is still being expanded and upgraded with Chinese assistance.

Once massive cross-border trade developed following the construction of the bridge at Jiegao in the early 1990s, and the subsequent proclamation of the enclave as a free-trade zone, the vision of a trade corridor through Myanmar became reality. China finally reached the Indian Ocean. China also soon emerged as Myanmars largest trade partner, political ally and supplier of military hardware to the military junta that then ruled the country. At the same time, Chinese companies became involved in the construction of several hydroelectric power projects in Myanmar that were to supply Yunnan and other southwestern provinces with electricity.

Myanmar connects China with the markets of South and Southeast Asia; more importantly, it provides China with an outlet to the Indian Ocean, thus bolstering Beijings quest for geostrategic influence.

Chinas interest in the Indian Ocean was first articulated in an article written by Pan Qi, a former Vice Minister of Communications, for the 2 September 1985 issue of the official Chinese weekly Beijing Review, thus well before even the establishment of the free-trade zone at Jiegao. Pans argument was that China would have to find an outlet for trade for the landlocked southwestern provinces of Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou, with a combined population of 160 million people. He mentioned the railways from Myitkyina and Lashio in the north and northeast of Myanmar respectively, and the Irrawaddy River that flows through Myanmar down to the Indian Ocean, as possible conduits for Chinese exports.

Pan also mentioned in his visionary article that there was a road connecting western Yunnan with southeast and west Asia quite early in history: Zhang Qian, a Han dynasty diplomat who lived from 202 BC to 220 AD, helped open a southern Silk Road from Sichuan, and the artery was travelled for centuries. But his attempts to forge a route from Sichuan to India proved unsuccessful. No southern Silk Road ever existed. In the past, China paid only scant attention to maritime ventures and it had had no presence in the Indian Ocean since the fifteenth century, when an explorer and trader called Zheng He sailed with his fleets to South and Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arab peninsula, and even as far as the east coast of Africa.

Apart from Zheng Hes voyages 600 years ago, there is no historical precedent for Chinas BRI, which consists of what the Chinese authorities call a Silk Road Economic Belt and a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. Together, these are intended to connect China It is the most ambitious development strategy in world history when it comes to one state supporting projects beyond its boundaries, surpassing even Americas Marshall Plan, which helped Europe rebuild after World War II.

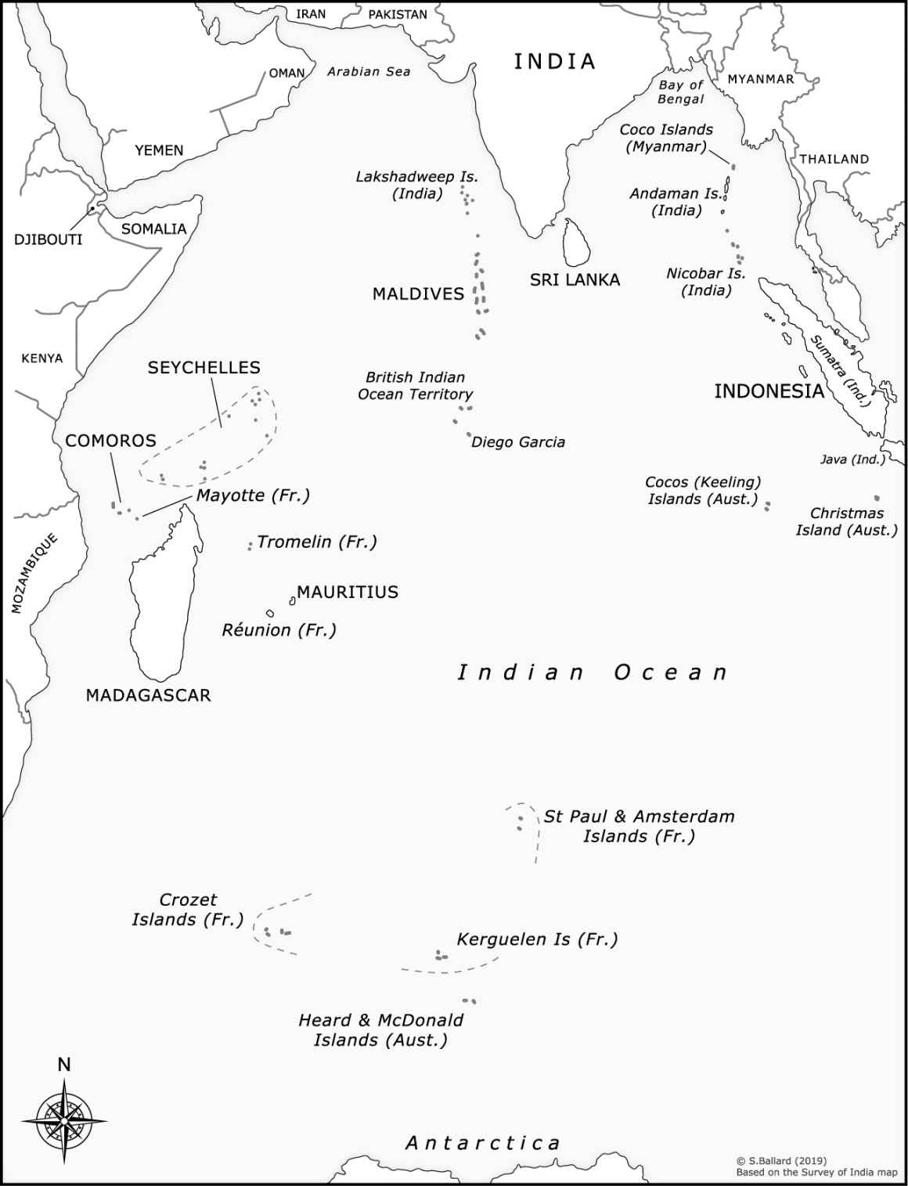

It is here that problems and potential conflicts become evident, as Chinas interests are bound to collide with those of existing Indian Ocean powers. Even other countries, which are dependent on Indian Ocean sea lanes connecting them with the rest of the world, have reason to be concerned about Chinas grandiose plans. Four-fifths of the container traffic between Asia and the rest of the world, and three-fifths of the worlds oil supplies, pass through the Indian Ocean. And now comes the BRI, which, if successfully implemented, may establish China as the dominant power in the Indian Ocean region.

Next page