THE EMPERORS NEW ROAD

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2020 by Jonathan E. Hillman.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) is a bipartisan, nonprofit policy research organization dedicated to advancing practical ideas to address the worlds greatest challenges.

CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author.

Center for Strategic and International Studies

1616 Rhode Island Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20036

202.887.0200 | www.csis.org

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020933559

ISBN 978-0-300-24458-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

T RAPPED IN NO MANS land, somewhere between China and Kyrgyzstan, I had time to think. Border guards at checkpoint five of seven had just started their lunch break, and I had to wait for their return. A few days earlier, I had attended the first Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, a massive and tightly choreographed celebration of Xi Jinpings signature foreign-policy vision for connecting China and the world. But on Chinas border, things were moving slowly, if at all. As minutes stretched into hours, the idea for this book was born.

In Washington, DC, and other Western capitals, policy makers heard about the forum in Beijing. They read about dozens of foreign leaders showing up, over sixty countries signing onto Chinas effort, ancient trade routes being revived, and other grand claims, often the same ones that Chinese state media tout. They saw maps of new economic corridors running outward from China. All these details add to an image of China as cunning, strategic, and marching in lockstep toward midcentury.

They missed the lunch breaks and border delays. From afar, the challenges standing in the way of Chinas global ambitions, including actual mountains, look smaller. Ironically, given an abundance of suspicion, relatively little has been done to check whether actions on the ground are advancing these ambitions. Quite understandably, most people cannot spend time crossing Chinas borders by car, foot, and boat or climbing onto its trains and docks in other countries, as I have done while writing this book. These pages share those glimpses of ground truth.

When the border guards returned several hours later and waved my vehicle through, arriving in Kyrgyzstan was something of a homecoming. In 2009, I lived in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstans capital, as a Fulbright scholar. I was fascinated by how Central Asia reflected and balanced outside influences. I was greeted by Asians who prayed to Allah, drank vodka, spoke Russian, ate Turkish food, listened to American music, and traded Chinese goods. I came to appreciate how the worlds crossroads provide a checkup of the global order.

Kyrgyzstan is different a decade later. Gone is the U.S. military base that served as a hub for troops and supplies going to Afghanistan. Chinas presence has poured out of the bazaars and into new roads, fiber-optic cables, and power projects. Xinhua, the Chinese state-media outlet, has opened a cultural center in Bishkek that sells copies of Xi Jinpings writing. Yet the Kyrgyz people are hardly sold. Rather than warming to Xis call for a community of common destiny, many are wary of Chinas influence and appalled by its internment of ethnic minorities.

This landscape, as I have tried to show it, has much in common with the past, but it is more complex than any Great Game or imperial contest. While the United States mostly complains these days, China is forging ahead. But it is not doing so alone or uncontested. Japan, India, Russia, and many others have their own designs. Far from being pawns, smaller countries are often the most pivotal players. Many of them have far more recent experience dealing with outside powers than China has acting as one. The road is theirs, as I hope it will remain for years to come.

PART I

Empire Strikes Back

Chinas Belt and Road Initiative

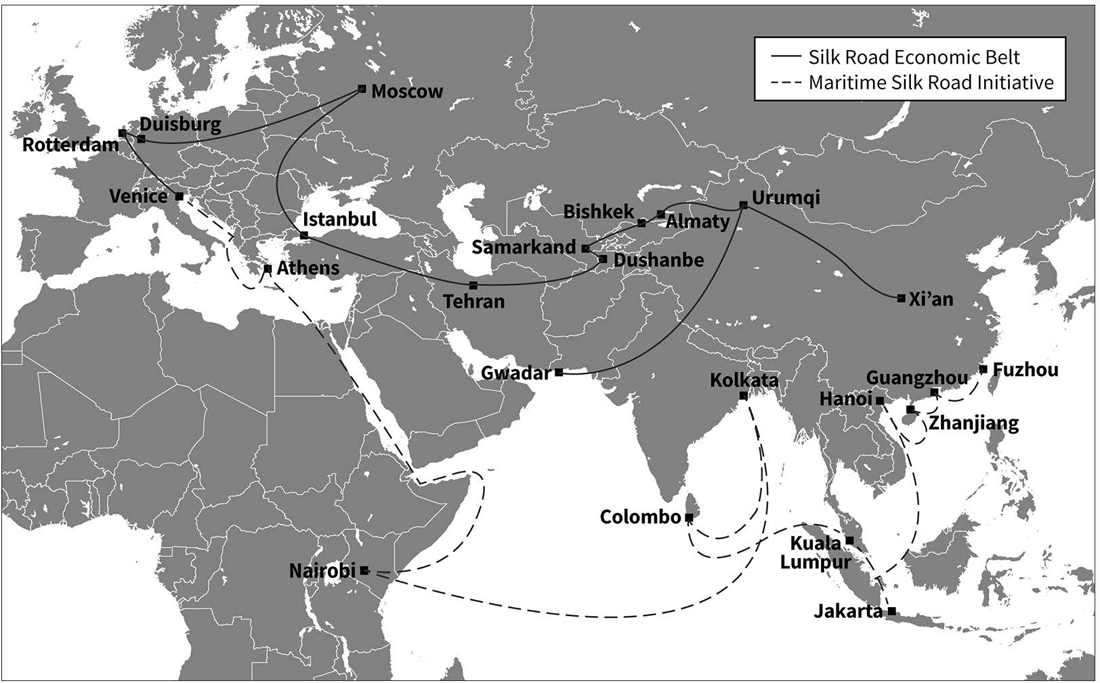

Center for Strategic and International Studies, Reconnecting Asia Project; Xinhua

CHAPTER ONE

Project of the Century

T HE ORCHESTRA STRUCK UP as the Peoples Leader entered the cavernous hall. As he strode down the red carpet, entourage at his back, his hundreds of distinguished guests stood and applauded. They fell silent when he took the dais.

Dear friends, he said, looking out at the sea of visitors. This is indeed a gathering of great minds.

In flattering them, he flattered himself. His friends numbered royalty, presidents, merchants, and intellectuals and were a Noahs ark of nationalities: Asians, Arabs, Africans, Europeans, Persians, and Russians. From all corners of the world, they had trekked to his court. Some came to pay tribute. Some came to trade. Others, like me, came out of curiosity.

It was a scene that Marco Polo might have recognized from his travels during the thirteenth century, but it was May 14, 2017, at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. President Xi Jinping stood before nearly thirty heads of state and delegates from over 130 countries. In the coming two days, he explained, we will contribute to pursuing... a project of the century.

But that was an understatement. Chinas Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), pursued to its end, stands to become the project of the century. Its size and reach are staggering. China has promised to

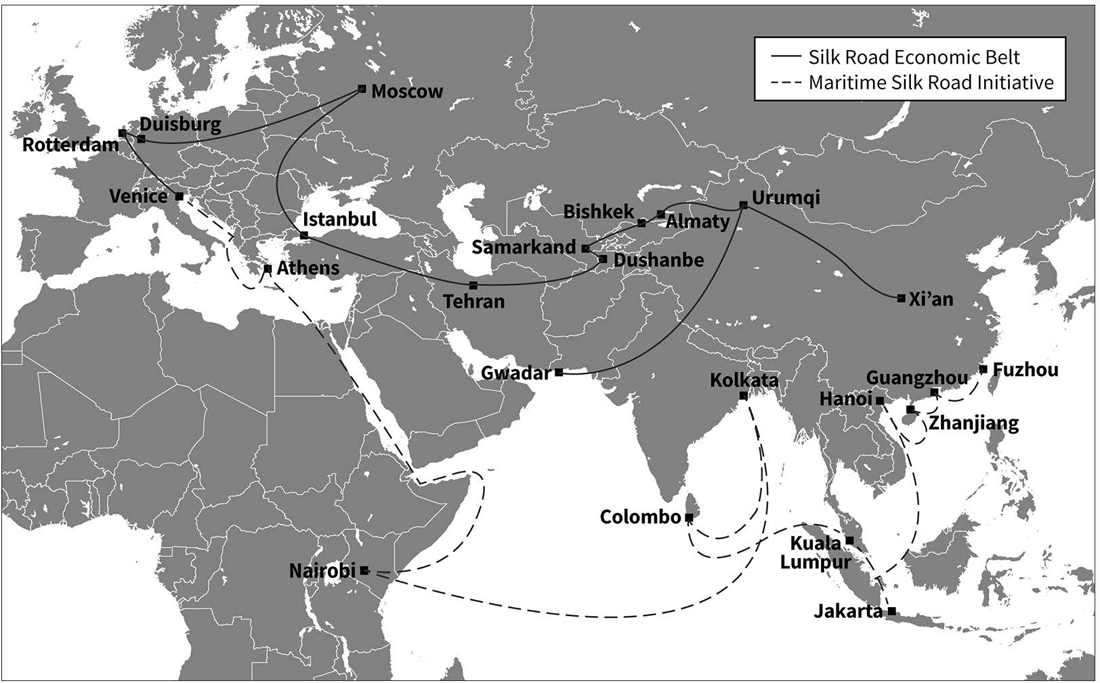

It is impossible to fathom the BRI without a map. When Xi announced the BRI in 2013, it had two key aspects: an overland belt across the Eurasian supercontinent and, somewhat confusingly, a maritime road across the Indian Ocean and up to Europe via the Suez Canal. Originally called One Belt, One Road, its purported aims are to deepen trade, investment, policy coordination, and even cultural ties. These new connections all have one thing in common: they lead to China.

Xis vision is constrained by neither geography nor even gravity. Since its announcement, the BRI has stretched into the Arctic, cyberspace, and outer space. The list of participants has grown to exceed 130 nations and includes not only Chinas neighbors but also most African countries and even countries in Latin America.

The same forces that powered Chinas meteoric rise are now being channeled through the BRI and beyond its borders. Over just a decade, China went from having no high-speed railways to having more than the rest of the world combined. Increasingly, Chinese companies challenge those from Japan, Europe, and other advanced economies for projects in world markets.

The BRI also provides a runway for Chinas bloated state-owned companies to take off and parachute into new markets. Between 2011 and 2013, China used more cement than the United States required during the entire twentieth century, and its ability to build now outstrips its domestic needs. The BRI is their safety net.

Next page