Contents

Guide

Published by University of Buckingham Press,

an imprint of Legend Times Group

51 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HJ

www.unibuckinghampress.com

First published in French in 2018 by ditions Fayard

Jean-Michel Steg, 2018, 2022

Translation Ethan Rundell, 2018

The right of the above author and translator to be identified as the author and translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

ISBN (paperback): 9781915054685

ISBN (ebook): 9781915054692

Cover design: Ditte Lkkegaard

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

For E., R. and G.

I Have a Rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple blossoms fill the air

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

Alan Seeger (18881916)

CONTENTS

Early 1917: The State of the Conflict on the Eve of the United

States Entry into the War

The German Spring Offensive of 1918 and the American

Baptism of Fire

What Was the True Military Impact of the Battle of

Belleau Wood?

FOREWORD

THE ARRIVAL OF THE AMERICANS, 191718

There has been an avalanche of historical writing published during the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War. And yet there is still one major omission remaining to be filled with respect to every front and every theatre of military operations. In short, the year 1918 is in need of attention.

Surprisingly, we still have no major account as to how the great stalemate of 191417 was broken, and why the strategic advantages the Central Powers held in late 1917 vanished a year later. These are still open questions, in part because of the complexity and transnational reach of the war. It is clear that the reasons why one side won are different from the reasons the other side lost, but a measured account of both is still to be written.

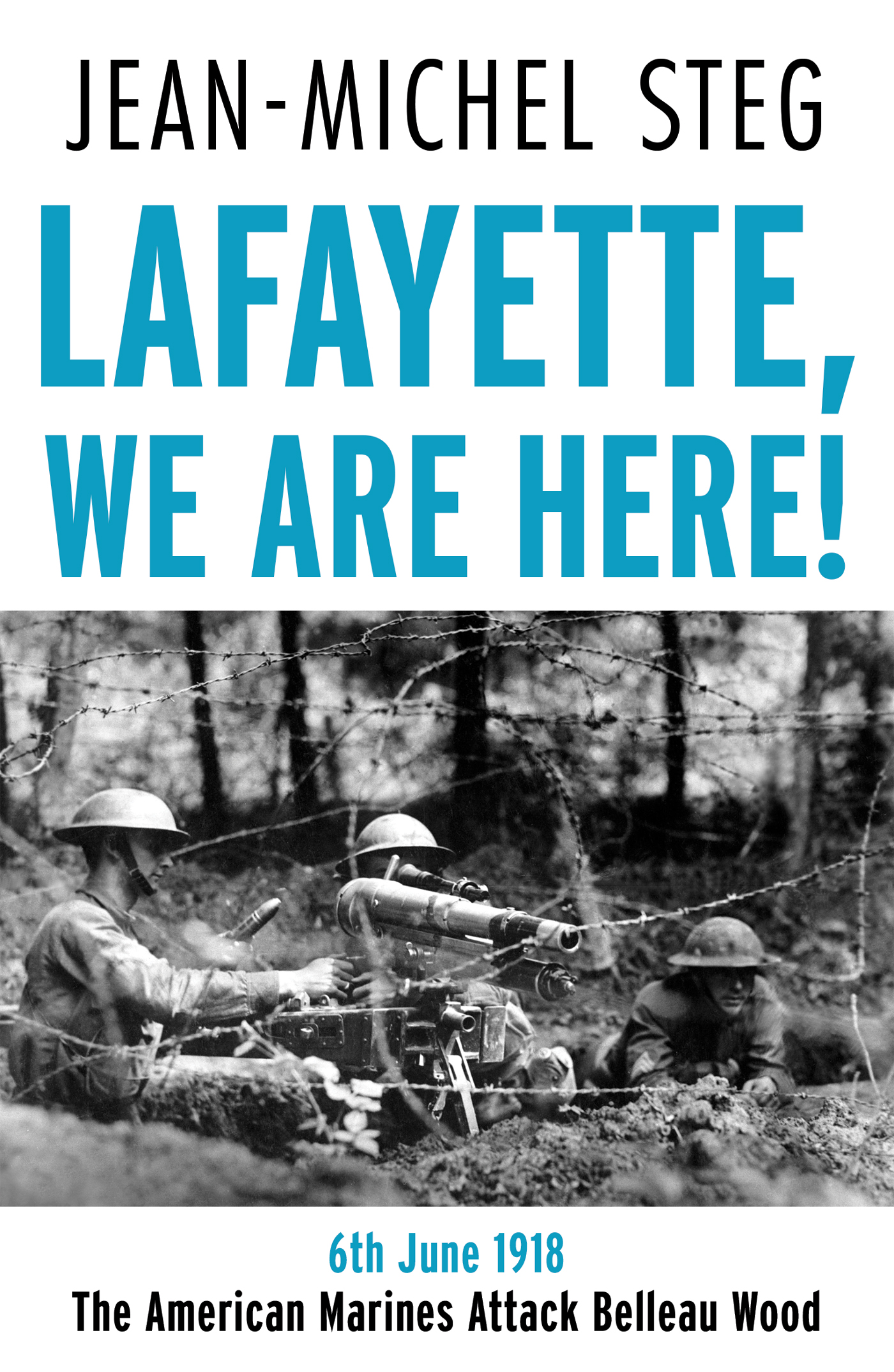

Jean-Michel Steg has provided a way forward in his multilevel account of the arrival of the Americans in the last year of the war. First, we see the war from the bottom up. Steg offers a splendid narrative of the taking of Belleau Wood by the US Marines in early June 1918. We see the confusion alongside the courage of the men on both sides and watch at eye level as the US Marine Corps breathes life into a legend which lasts to this day.

Secondly, we see the war from the top down and come to locate nasty encounters like Belleau Wood within the framework of the turning point of the war, separating the stalemate of 191417 from the war of movement and endgame of 1918.

Above all, Steg shows us that American entry into the Great War in April 1917 did not end it. What the United States did in 1917 was to prolong the war, at a time when Russia was in revolutionary turmoil and when Britain and France were stretched, almost to the breaking point, both in terms of manpower and financial power.

US help in stabilizing the Allied cause was of even greater significance in 1918. What the United States did was to present to the German army and government in 1918 a terrible prospect for the future. When the March 1918 offensive failed, what they could no longer ignore was the likelihood of facing 3 million more American troops in the very near future. Thus it was not American power on the Western Front in 1918 but the projection of American power into 1919 and 1920 that made the difference to both Allied and German thinking about which side would win and which side would not win the war. For the German high command, that recognition came late, in the summer of 1918, and not one second before. Their monumental arrogance is well known and so is their underestimation of the ability of the United States to project its power overseas. They made the same mistake twenty-five years later.

We see that the anticipation of future massive injections of American troops into the lines mattered to the Allies, too, since the longer the war went on, the more the United States would be able to dictate the terms of the peace. As an associated power rather than an Ally, Americas voice was strong but not dominant in 1917. By the autumn of 1918, British and French forces were exhausted, giving to the United States a greater and greater role both in the way the war was fought and in the way the peace would be drafted. For Britain and France, the time for an armistice had arrived in November 1918, before the Americans took over the war; General John J. Pershing, the American commander, thought otherwise and planned a thrust into Germany in late 1918 and early 1919. He was overruled by Marshal Ferdinand Foch, commander of all Allied forces, who thereby preserved a balance among the victorious powers, which lasted (just about) until the Peace Treaty was signed on 28 June 1919. This war among Americas allies about who would frame the peace is one we cannot neglect in our understanding of how and when the war ended.

Once again, Stegs account provides a fresh account of this crucial period in international history. He shows that the American army did not win the war. The performance of American forces on the field of battle was mixed. The open warfare ordained by the American approach to battle never happened, although American power mattered, especially in set encounters like Belleau Wood, and, even more importantly, in the MeuseArgonne offensive. The use of tanks was only marginally successful in the muddy and broken terrain of the Western Front, turning Pattons incipient Tank Corps into fixed artillery. In this way, Steg shows that the Americans were just as perplexed as their allies as to how to adjust their thinking about war to the novel conditions of the Western Front.

We see too that under French command, American forces including African American forces performed well in filling gaps in the line. Under American command, African American soldiers were treated like coolies, lest they get uppity and be ruined before their return to segregated America.

The bottom line is that, on the whole, US units operated just like French and British units in 191516. They had to undergo a learning curve, which wound up as a bleeding curve, especially in the last four months of the war. Then US forces were hit by the Spanish flu indeed, it is possible that they brought it with them. One of the centres of incubation and dissemination of the mutant virus was the major American army base at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. Doughboys died by the thousands even before they got their travel orders to sail across the Atlantic, but then millions of men on both sides of the lines joined the long list of victims of this mutant viral infection.

We owe Jean-Michel Steg a vote of gratitude for giving us his insights not only on the last phase of the Great War but also on the way the Great War left its mark on the American way of war. Many of the leading players in the Second World War MacArthur, Patton, Marshall, Truman had their baptism of fire in industrial warfare in 191718. What they learned informed what they did in their later careers. The long shadow of 191718 in France reaches well into the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. Its traces linger still.