Chivalry and the Perfect Prince

Habent sua fata libelli

S IXTEENTH C ENTURY E SSAYS & S TUDIES S ERIES

G ENERAL E DITOR

M ICHAEL W OLFE

St. Johns University

E DITORIAL B OARD OF S IXTEENTH C ENTURY E SSAYS & S TUDIES

C HRISTOPHER C ELENZA

Johns Hopkins University

M IRIAM U . C HRISMAN

University of Massachusetts, Emerita

B ARBARA B . D IEFENDORF

Boston University

P AULA F INDLEN

Stanford University

S COTT H . H ENDRIX

Princeton Theological Seminary

J ANE C AMPBELL H UTCHISON

University of WisconsinMadison

R OBERT M . K INGDON

University of Wisconsin, Emeritus

R ONALD L OVE

University of West Georgia

M ARY B . M C K INLEY

University of Virginia

R AYMOND A . M ENTZER

University of Iowa

H ELEN N ADER

University of Arizona

C HARLES G . N AUERT

University of Missouri, Emeritus

M AX R EINHART

University of Georgia

S HERYL E . R EISS

Cornell University

R OBERT V . S CHNUCKER

Truman State University, Emeritus

N ICHOLAS T ERPSTRA

University of Toronto

M ARGO T ODD

University of Pennsylvania

J AMES T RACY

University of Minnesota

M ERRY W IESNER- H ANKS

University of WisconsinMilwaukee

Copyright 2008 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri USA

All rights reserved

tsup.truman.edu

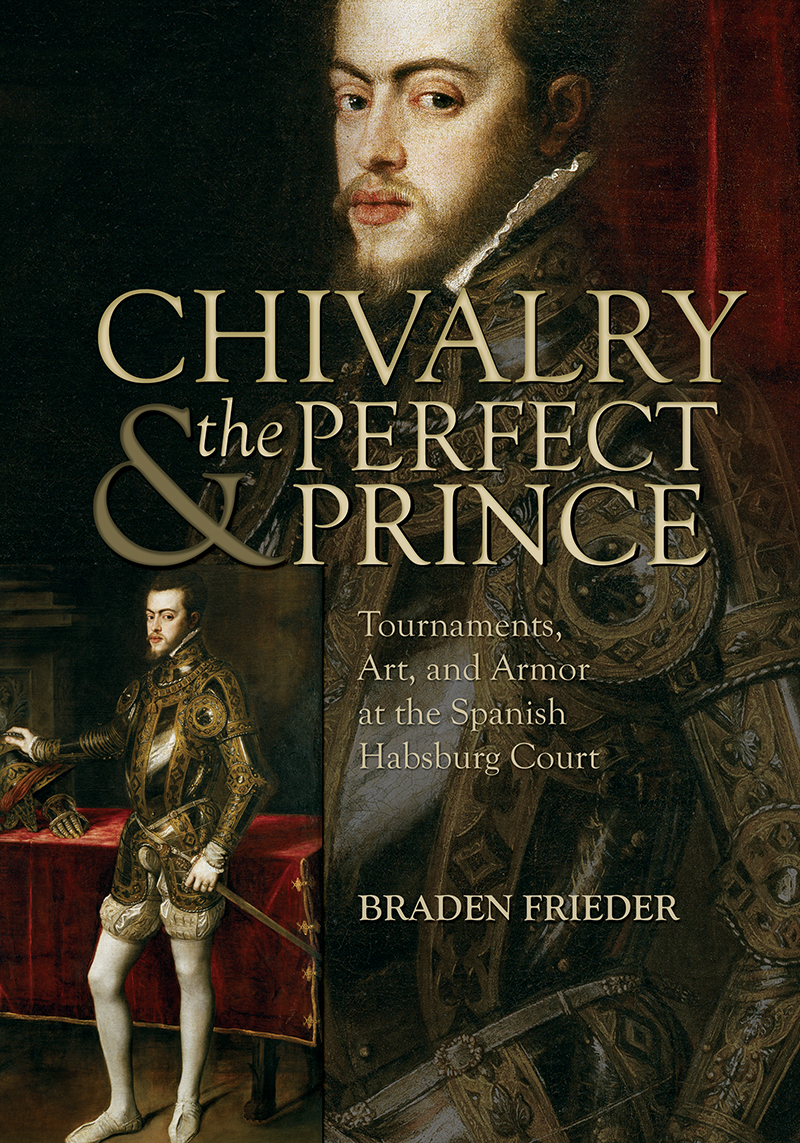

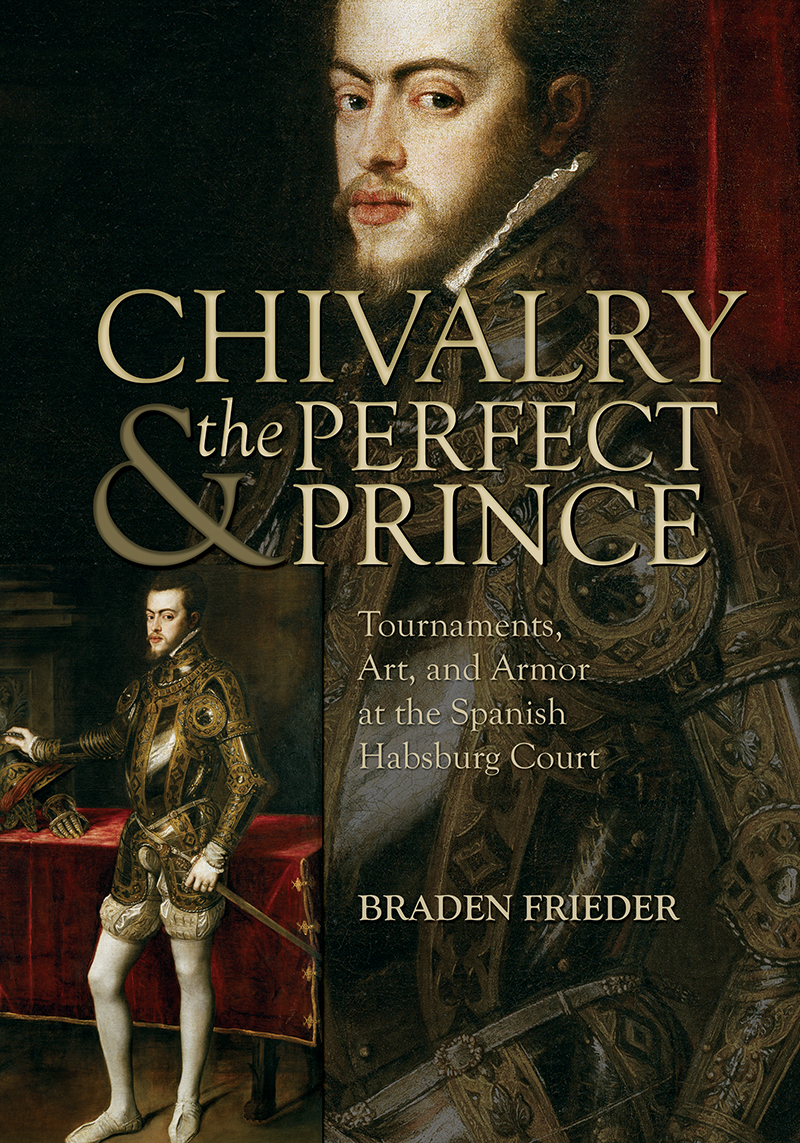

Cover art: Titian, Portrait of Philip II, 1549. Oil on canvas. Madrid, Museo del Prado (411). Used by permission.

Cover design: Teresa Wheeler

Type: Goudy Old Style, URW

Printed by: Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Frieder, Braden K.

Chivalry and the perfect prince : tournaments, art, and armor at the Spanish Habsburg court, 15041605 / Braden K. Frieder.

p. cm. (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 81)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-931112-69-7 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. Armor, RenaissanceSpain. 2. Tournaments, MedievalSpain. 3. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, 15001558. 4. Philip II, King of Spain, 15271598. 5. Knights and knighthood in art. 6. Kings and rulers in art. I. Title.

NK6662.A1F75 2008

394'.70946dc22

2008000748

No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher.

The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

NOTE: Sequential numbers in square brackets [] in the body of the text refer to page numbers of the print edition; citations appeared as footnotes in the print edition.

Note: Because of display limitations of e-readers, some special characters (e.g., Greek or Hebrew letters, cedillas, characters in Eastern European languages, accents or other diacritical marks) may ont display properly in the e-book version of this work.

To My Wife

Contents

The origin of this book was a visit to the Royal Armory in Madrid. As a young history student, I was attracted to the suits of decorated armor made for Emperor Charles V and his son, Philip II of Spain. Renaissance princes wore decorated armors not only for protection, but also as status symbols. I was intrigued by the idea that these suits of armor were really costumes for a kind of royal theater in which the ruler appeared to his people as the descendant of ancient gods and Christian heroes. The stages on which the prince acted out this role were the tournaments, state entries, and military campaigns of the Renaissance. The actors in these events commissioned armor and other artworks specifically for these occasions, their collective iconography expressing Renaissance ideas of the perfect prince. This common vocabulary of chivalric imagery was linked to historical events and to the unique problems faced by the Habsburg regime. By the middle of the sixteenth century, European monarchs rarely led their own troops into battle, though the worth of a ruler was still conceptualized in military terms. The ruling dynasty used the visual language of the tournament and martial display to symbolically affirm the legitimacy of their rule and the identity of the prince as a divinely appointed deliverer.

When I began my study, I found that, although there is a fair amount of literature on the connoisseurship of Renaissance armor, relatively little had been published on the context and meaning of these splendid artifacts. Shifting my research to courtly spectacle and festival art in the sixteenth century, I found that books and articles in recent years have tended to sideline the tournaments that accompanied the ceremonial entries of visiting princes. A closer examination of Renaissance spectacle shows that the tournament in the sixteenth century was not peripheral to the royal entry, but central to it. A search through the available literature on tournaments provided better hunting, but the main object of the chase still proved elusive. Compared to the large volume of material published on military history, only a handful of books were devoted to the tournament itself. For the most part, these studies focused on medieval tournaments, with the Renaissance tournament treated as a kind of denouement. This seems strange indeed, considering that the tournament as an art form reached its apogee in the Renaissance. The tournaments held at the courts of sixteenth-century European monarchs were unsurpassed in size and splendor, and were remembered in these terms by contemporary writers on the subject. Their descriptions proved to be the most fruitful primary sources for my study, and form the basis for this book.

As Malcolm Vale points out in War and Chivalry, the comparative lack of interest in later chivalry can probably be traced to the writings of the cultural historian Johan Huizinga (18721945). Echoing the German philosopher Hegel, Huizinga believed every age in history was pervaded by its own fundamental spirit that determined all forms of cultural life. In the late Middle Ages, when the tournament-as-spectacle took shape at the courts of Burgundy and Flanders, the spirit of the age, according to Huizinga, was one of decadence and decline. This view continues to inform much of the current scholarship on chivalry and tournaments. Modern historians have also emphasized the widening gap between chivalry and real life at the end of the Middle Ages. People living in the Renaissance, however, were unaware that chivalry was in decline. The Jouvencel, based on a fourteenth-century manual of knighthood, went through five printed editions between 1493 and 1529. The tournament was still alive and well at the courts of Queen Elizabeth and King James of Scotland at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Apart from religion, chivalry remained the strongest of all ethical considerations, particularly among the ruling classes. Contemporary views on the subject are suggested by a curious incident alleged to have taken place following the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Emperor Charles V, exasperated with Francis I for breaking an oath taken as a condition of his release from captivity after the battle, challenged the king to personal combat as a way of settling their differences. Knightly warfare may have been out of date, but chivalric values were not.