Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

to Pierre Vincent: priest, organist,

friend, and son of Rouergue

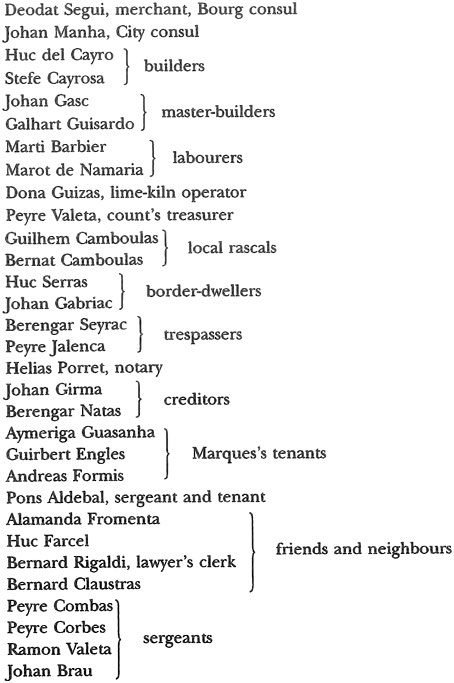

THE MARQUES FAMILY

Peyre Marques, cloth-seller

Alumbors Marques (formerly Rostanh), his wife

Johan, his son

Guilhema, his daughter

Gerald Canac, his son-in-law

Bartelemi Marques, his uncle

Huc Rostanh, his brother-in-law, cathedral canon

Ramon Griffe, priest, his minder

BUILDERS, NEIGHBOURS, CREDITORS, FRIENDS

The principal system of currency in Rodez was livres, sous and deniers. As in the old British money, 12 deniers made one sou, and 20 sous made one livre. Rodez added a complication: these coins were sometimes weak local issue minted by the count (livres, sous and deniers rodanes ), and sometimes livres, sous and deniers tournois, a stronger and more centralised currency which was also the official currency of account. Unless otherwise specified, the tournois currency is the one used here. The denier was also worth two obols, or halfpennies.

Readers will also encounter florins, francs, marks and other foreign coins. These were interlopers, but in time of war any coin was acceptable if its pure-metal content was high enough. Rates of exchange were too variable to mention.

THIS BOOK IS about a divided town, with a political frontier running through it. We know such frontiers well in the late twentieth century. We know that they can run through villages, houses, even kitchens; and that they can divide people of the same race, the same language, the same religion, the same family. Racial and tribal frontiers, the sort that produce ghettoes in cities, are of another kind; they may often be natural or voluntary. Political frontiers are always imposed by the authorities for reasons of power, rivalry or convenience of rule; and men have then to decide whether to live with these artificial constraints, or find a way round them.

The story focuses on the strange case of Peyre Marques, a merchant who forgets where he has buried his gold. When, in 1370, two workmen discover a hoard of coins while unblocking a drain, Marquess pathetic situation becomes for us the centre of a detailed canvas that takes in the history of the town and lights it up against a background of compassion and brutality, cruel justice and individual acts of kindness, shadowed by the ever-present threat of attack.

Peyre Marques, the chief character in this book, is the man I have singled out to tell this tale of partition. He is the thread that runs through the whole fabric: together with his wife, his son-in-law, his neighbours, his tenants, his brother-in-law and his creditors. These people lived with partition every day, and partition in turn worked on them; they were its victims and in some ways, also, its perpetrators. They are the guides we need.

The story of Marques was preserved quite accidentally. We know about him only because a pitcher of gold was found buried in the floor of his shop. His son-in-law took it away, and ownership of the money was disputed in court. The result was a full-scale inquiry detailed character references, anecdotes, gossip about a man who was perfectly ordinary: just a middling businessman trying to support his family, stay solvent, keep his wife happy, keep his wits together. For that reason alone, this case is precious. History keeps memorials of the great, the saintly or the vicious, but we may pine for the chance to hear about men and women more like ourselves: common folk. Marques was preserved, in effect, in the tittle-tattle of his neighbours. Reading the documents about the jug of gold, we hear the ancient equivalent of lace curtains being moved aside.

To the modern eye, Marques with his confusions and obsessions, his steady loss of business acumen, his sharp long-term memory and vagueness about the present seems likely to be one of the earlier recorded sufferers from mental illness, possibly Alzheimers Disease. That may provide another reason, together with political partition, for twentieth-century readers to involve themselves in such a distant story. But we shall never know for sure what Marques suffered from. All we can say is that his case is like an archaeological section that allows us, by concentrating on a tiny area, to go down deep through the layers of medieval life and the peculiar pressures of a partitioned place.

The background to this story, beyond partition, is war: the Hundred Years War, fought for sovereignty and land between two powers which were both essentially foreign to Rodez, England and France. This war had been going on, in an intermittent succession of truces, pitched battles and wild skirmishes, since 1337. The Treaty of Brtigny, in 1360, gave King Edward III of England lordship over all the lands he had formerly held as a vassal of the King of France, including, at the furthest eastern edge, the City and castle of Rodez and the pays of Rouergue. This, and the broad area stretching westwards to the sandy Atlantic coast of Aquitaine, fell under the charge of the Black Prince, Edwards eldest son, who thus became the suzerain of Rodez. But in 1364 the new king of France, Charles V, re-opened hostilities; and the Count of Rodez, Jean I of Armagnac, who had always been opposed to the Black Prince for his own local reasons, began to gravitate to the French cause. By 1369, the town could be counted in the French camp but only just.

These grand strategies, however, hardly touched men like Marques. Two other problems bothered them more. The first was that the war had become an endless series of guerrilla eruptions, interrupting trade and travel, terrifyingly unpredictable. The people of Rodez, though physically almost untouched by fighting, were scared of it almost all the time. The town stockpiled food and weapons, and watch duties were organised to involve as many people as possible, even down to teenagers and friars. But the main effect of war, an indirect one, was crippling taxation. It could be said that Marques was ruined by the war between England and France as surely as any traveller who met with mercenaries on the road. And that, too, is part of the story.

* * *

The case of Peyre Marques is found in court registers which go into considerable detail. It is possible to hear him talking (in his own words), to hear his neighbours talk, and so to derive a great deal of information about him, his wife, his relations, and the main characters. It is possible to reconstruct dialogue and even to recover chance remarks, and I have tried to do this wherever possible: but only when the material allows it, and where no violence is done either to fact or to the integrity of the actors. History may need the zip of fiction, but any frisson it delivers must come from the fact that what is related really happened, or was really said. So if dialogue occurs in this book, it is as it was spoken then and recorded at the time, and it is not in any way invented; if incidents are recounted, that is because they took place, and I have added nothing to embroider them.