Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

Claude Bryon Price

November 8, 1914August 2, 1972

Maggie Lucille Smith Price

February 6, 1913January 29, 1999

George Washington Hawkins

January 3, 1916August 7, 1980

Alma Marie Pierson Hawkins

October 8, 1920January 11, 2004

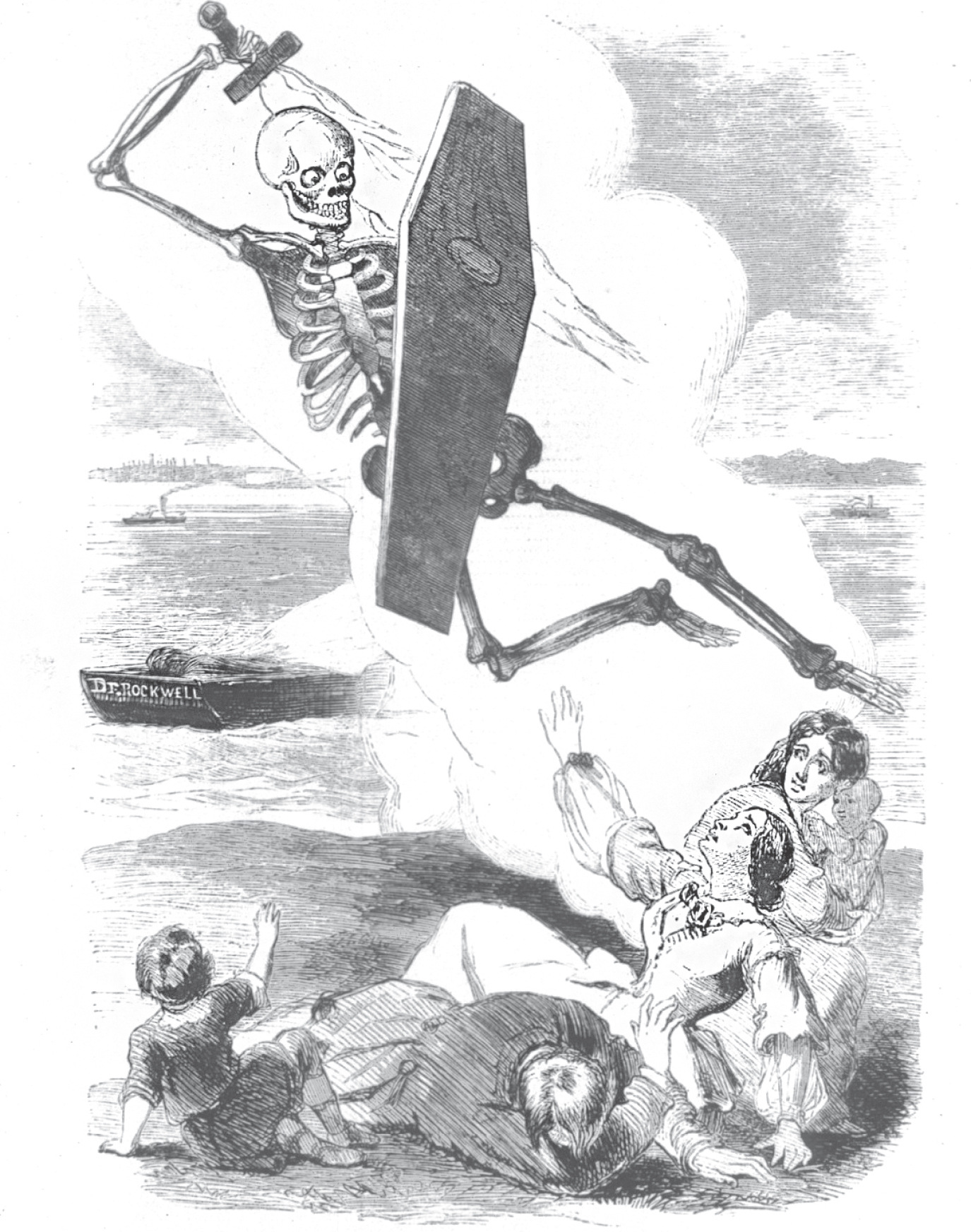

Death Rising from the Iron Scow and Scattering Pestilence Among the People, Harpers Weekly, October 2, 1858.

PREFACE

I n early January 2020, the Chinese government sealed off Wuhan, larger in population than New York City, from the rest of China and the world. Fearing the potential spread of a mysterious illness that had already taken seventeen lives and made more than six hundred other people ill, officials shut down public transportation and blocked highways. In the weeks to follow, the measures became more drastic still. The government extended the quarantine-style lockdown to include more than fifty million people living elsewhere in China. Officials ordered door-to-door checks in Wuhan to round up the infected for isolation, confining residents and visitors alike in an attempt to stop the spread of a new coronavirus that Americans would come to know as COVID-19.

As Americans viewed Chinas heavy-handed response, national news media asked whether the US government could take similar authoritarian measures, and over the next year I commented on legal matters ranging from lockdowns to face masks to vaccination mandates. Journalists wanted to know why state governors could impose wildly varying health measuresor none at all. I knew the weak points in Americas ability to respond to epidemicsthat the key issues were not really about COVID itself. I knew we could expect conflict and turmoil, even if I could not have foreseen just how poorly the US would fare compared to many other nations. I also served as an expert adviser to both the National Governors Association and the Uniform Law Commission, the nations oldest state governmental association, on legal issues related to the nations COVID-19 response. Yet despite my years of study and thinking about the ways our legal system governed epidemic emergencies in the past, I confess to many, many deer-in-the-headlights moments.

I had seen the fault lines before. During the 2014 Ebola crisis, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), just up the street from my office at Emory University, were on the front lines in West Africa and in the political hot seat for preventing the Ebola virus from spreading to the United States. Emory University Hospital treated the first American health workers evacuated from West Africa, over protests and bomb threats by some members of the public. Fear intensified after an Ebola victim died in Dallas and two nurses there developed the disease. Fortunately, there was no further spread of Ebola in the country.

But the response of government officials at all levels exposed the fault lines in our ability to control a future, fast-moving epidemic. An understandable but unwarranted public panic led to actions by political leaders that undermined confidence in the governments ability to protect us from deadly contagion. Several governors squabbled publicly with the federal government about who was in charge, about whether to close borders, and about who should be quarantined.

I knew the underlying reasons for what Americans were seeing in 2014, and again with COVID-19, because I have studied and written about Americas response to past epidemics for many years. History teaches us that effective disease control is a matter not just of containing (or better yet, killing) pathogens but also of implementing effective laws and governance. We rely on democratically chosen governments to fund research, distribute vaccines, pursue cures, and take other protective measures to control contagions. Our laws and legal system have sometimes aided the efforts of scientists to stop an outbreak and sometimes have proved a hindrance. But epidemics also create conflicts among citizens, sometimes exceedingly bitter ones, as yellow fever did in the late nineteenth century. Ultimately our political system and laws must address those.

We expect government to keep us safe from epidemics. But the United States has a spotty record of doing so, and this book helps explain why. Epidemic control in the US is unique and controversial because of our deep culture of individual rights and constitutional values. Epidemic control is also made more difficult because the US has one of the most decentralized and fragmented public health systems in the world.

Drawing from our past, I provide a legal history of epidemics that the United States has experiencedincluding smallpox, yellow fever, the Spanish influenza, polio, HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and, now, COVID-19. Choosing 1776 as a starting point to recount Americas past epidemics as I dorather than, say, 1492 or 1607 or 1620admittedly ignores more than two centuries of colonial government as well as centuries of customary measures to prevent the spread of diseases whose causes were little understood. But the establishment of a new nation on the shores of North America created a set of circumstances that would shape a law of epidemics in distinctive ways. The constitution of a federal government that also vested great authority in the individual (and very different) states that made up the nation led to the unusual history that unfolds in this book.

Laws concerning epidemics did not change much in Americas first century, after the colonists formed themselves first into independent states and then a nation. As it happens, we still operate with some of the same laws and governing structures that were put in place then to contain disease outbreaks. Those laws still work in many circumstances, as they did when small communities and rural living were the norm, travel was slow and cumbersome, and medical science had few of the tools that we now take for granted. But as the nation expanded and opened up to greater commerce and faster means of transportation after the Civil War, epidemics had a profound effect on the country and reshaped the government institutions and laws that helped meet those emergencies.

Most people do not think of government and legal issues when they think of epidemic disease, but health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic present a crisis not only for doctors and public health officials but also for lawyers and politicians. Medical experts may advise burdensome measures to halt the progress of a pandemic, but the lines of authority among local, state, tribal, and federal officials are often unclear and contested, as the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated. Public health becomes political, as constituents demand governmental responseor demand that it not respond in a particular way. These fault lines have been with us for a long time.

From Americas earliest epidemics, political leaders faced strikingly similar challenges and made strikingly similar decisions. In the years since, we have lacked the political will to strengthen the nations public health defense system. We have inherited and retained inadequate laws, have underfunded public health agencies, andmost to the pointcontinue to respond to pandemic threats in the United States not as one nation, but as fifty-five smaller nationsthe states, territories, and commonwealths that politically subdivide the country. Americas public health defense is further divided among nearly three thousand state and local public health departments. We rely on them to protect us from outbreaks of contagious disease in our communities. But jurisdictional boundaries are jealously guarded, in part because of a philosophical preference toward local control and in part to preserve limited budgets. With this setup, it is difficult, if not impossible, to have an effective national strategy against a pandemic.