SALVATION AND SUICIDE

Religion in North America

Catherine L. Albanese and Stephen J. Stein, Series Editors

SALVATION

AND

SUICIDE

JIM JONES, THE PEOPLES TEMPLE, AND JONESTOWN

REVISED EDITION

DAVID CHIDESTER

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47404-3797 USA

http://iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail

1988 and 2003 by David Chidester

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and

recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of

American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes

the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements

of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence

of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chidester, David.

Salvation and suicide : Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and

Jonestown / David Chidester. Rev. ed.

p. cm. (Religion in North America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-34324-6 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-253-21632-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Peoples Temple. 2. Jones, Jim, 19311978. I. Title. II. Series.

BP605.P46C48 2003

289.9dc21 2003007226

3 4 5 08 07

TO THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

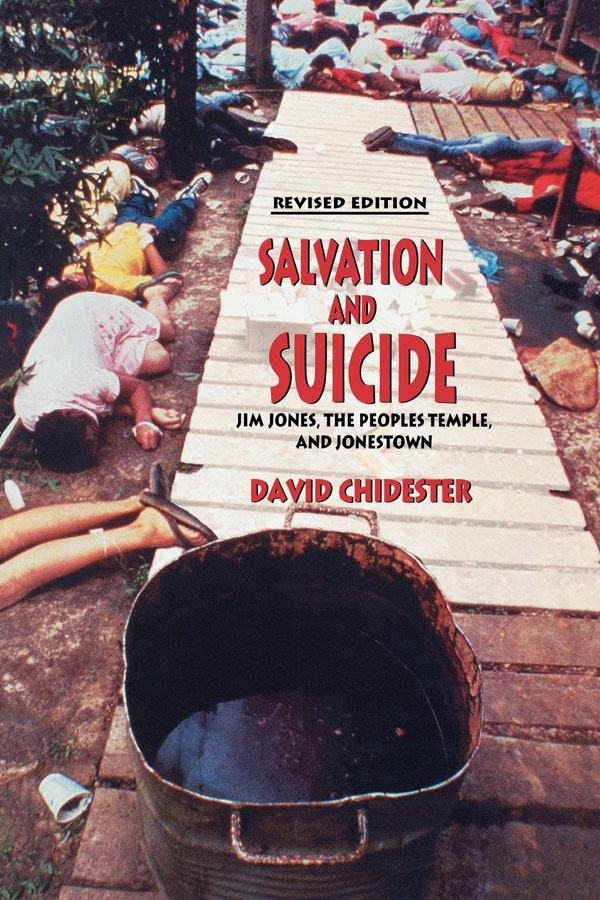

In November 1978 many in the guild of religion scholars were gathered at New Orleans for the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion. As professionals we had come together to apply critical method from varying disciplinary perspectives to the phenomena of religion. When news of the white night at Jonestown broke at our meeting, it came with a strange surrealism. There was, it seemed, nothing in the resources of an entire tradition of scholarship that could enable us to grasp what had happened, to fit it into an interpretive framework that would make religious sense of it. Instead, members of the academy seemed left much as everyone else, bereft of any superior insights to come to terms with the raw event. There was, indeed, a subtle irony in our professional confidence regarding religious studies when juxtaposed with our conceptual difficulty in dealing with the decades, and perhaps the generations, most dramatic religious happening.

Now, some ten years later, David Chidester has taken a major step to bring the event of Jonestown into the province of the academy of religion. After an era of interpretation marked mostly by sensationalized journalism, facile psychologism, and relatively limited social science analysis, Chidester has shownfor the first time in a book-length workthat it is possible to understand Jonestown in religious terms. Distinguishing between the private religious world of Jim Jones and his public theology mediated through his sermons, Chidester points to the connections between the religious worldview of Jones and the organizing ideas of the Peoples Temple. Thus for Chidester the murder-suicide that framed the climactic moments of the Temple was, insofar as it was suicide, religious suicide.

That this is a provocativeand courageousinterpretive approach should be clear. Nor does Chidester soften the hermeneutic by ritual reminders that Jones was an evil man or at least a crazy one. Instead, with an impressive display of consistency, he carries his phenomenological method as far as it will go, demonstrating again and again his grounds for understanding Jones and Jonestown as distinctively human in idea and enterprise. The message of his work is clear: whatever else Jim Jones and Jonestown may have been, they were expressions of self-conscious and intentional religious possibility.

In arguing boldly for his thesis, Chidester has gone as boldly for the primary sources on which to build it. He has listened to and transcribed hours of tapes ignored, in their interpretive import, by other authors. He has tracked and read virtually every item that has been published on the Jonestown experiment, whether the work of insiders or outsiders. And he has mined these sources to provide us with the most complex and detailed account of the religious teachings of Jim Jones that has yet appeared in print.

Not everyone will agree with Chidesters interpretation of these teachings or with his reading of the Jonestown white night. Nor will all be persuaded by his religious phenomenology. Nonetheless, we are all indebted to him for a path-breaking work that restores the interpretation of Jonestown to the place where it belongsthe academy of religion scholars. His study, we believe, marks the beginning of a new epoch in Jonestown scholarship.

C ATHERINE L. A LBANESE and

S TEPHEN J. S TEIN , Series Editors

PREFACE

All ancient history is equally ancient. Already, ten years after the fact, the events that transpired on November 18, 1978, in the jungles of Guyana seem distant, remote, beyond recent memory, demonstrating that even recent history can be ancient history. As accounts of the mass murder-suicide at Jonestown recede from memory, the event can be reconstructed only through historical imagination. This book is an exercise in historical imagination that attempts to recover the memory of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown by reconstructing the worldview that animated the church, the movement, and the utopian community that self-destructed on November 18, 1978. This book is a chapter in recent, ancient American religious history.

A sense of distance from the Jonestown event was present, however, even at the moment the news hit the streets of the first assassination of a United States congressman in American history, the apparently unprecedented mass suicide of over nine hundred members of the Peoples Temple, and the postmortem removal of the bodies of the Jonestown dead from Guyana to the United States. The Jonestown event was unimaginable, yet it preoccupied the news media and popular imagination for months by generating accounts of brainwashing, coercion, beatings, sexual perversions, horror, and violence. Public interest in the Jonestown event revealed a curious mixture of attraction and repulsion. Attracted and repelled by the pornography of Jonestown, Americans could only come to terms with accounts of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown through strategic explanations that controlled information about the Jonestown event in a way that served to reinforce the normative boundaries of shared psychological, political, and religious interests in America. Any historical reconstruction of the Jonestown event must certainly include the ways in which the event was received. Rituals of exclusion, cognitive distancing, and strategic explanations of the event were ways in which Americans reinforced the boundaries of the normal that were potentially disrupted by the Jonestown event.

Overlooked in almost all explanations of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown is their religious character. The Peoples Temple was a religious movement, animated by a particular religious worldview, that can be interpreted in the larger context of the history of religions. Cross-cultural, comparative, and interdisciplinary categories of the history of religions provide an interpretive framework within which an understanding of the Peoples Temple might emerge, take shape, and grow. I do not claim to be able to explain Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, or the Jonestown event. However, before any explanation can be offered, detailed work of religiohistorical description, interpretation, and analysis is necessary in order to reconstruct the symbolic systems of classification and orientation that operated in the worldview of the Peoples Temple. A religiohistorical interpretation of that worldview establishes the conditions necessary for an understanding of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown in the context of the history of religions.