The British Navy in Eastern Waters

The British Navy in Eastern Waters

The Indian and Pacific Oceans

John D. Grainger

THE BOYDELL PRESS

John D. Grainger 2022

All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation

no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system,

published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast,

transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission of the copyright owner

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as

the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with

sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published 2022

The Boydell Press, Woodbridge

ISBN 978 1 78327 677 6 hardback

ISBN 978 1 80010 459 4 ePub

The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd

PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK

and of Boydell & Brewer Inc.

668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 146202731, USA

website: www.boydellandbrewer.com

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate

Cover image: The English East Indiaman Pitt engaging the French ship St Louis off Fort St David, near Pondicherry, 29 September 1758 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Cover design: Greg Jorss

Maps

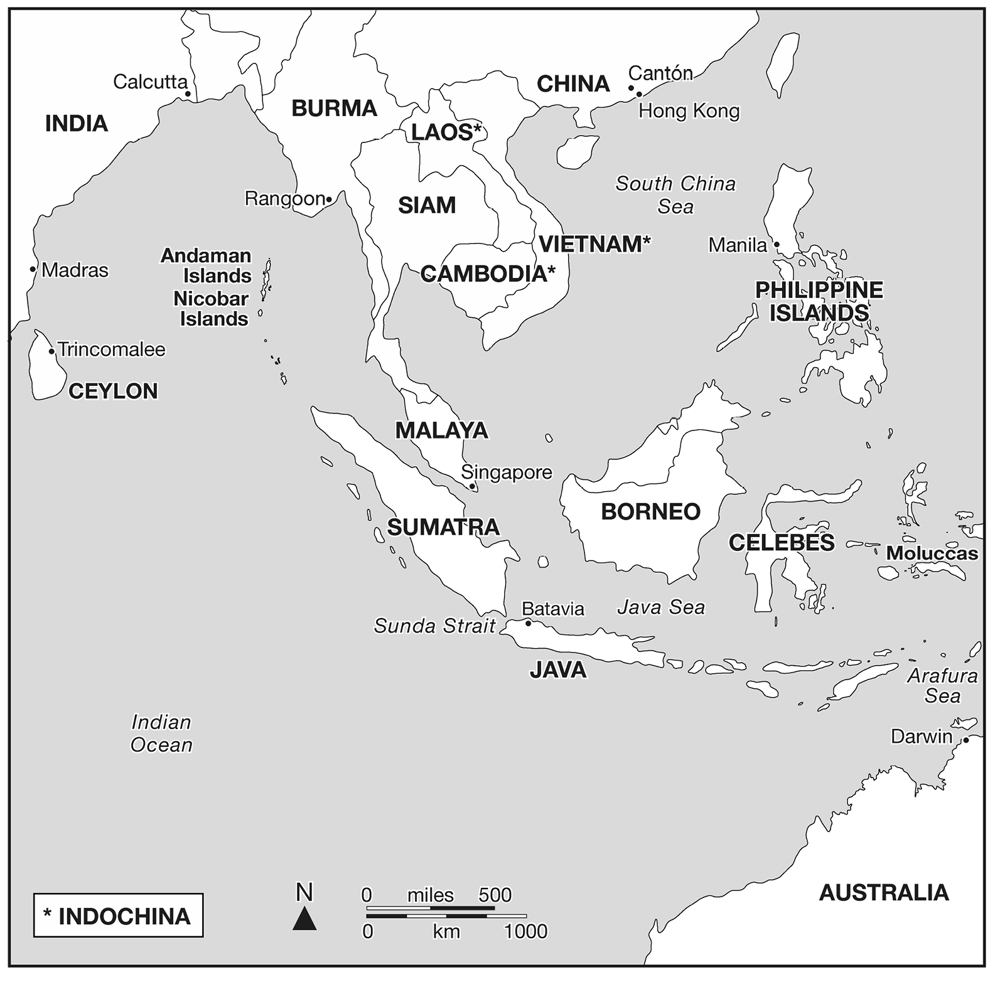

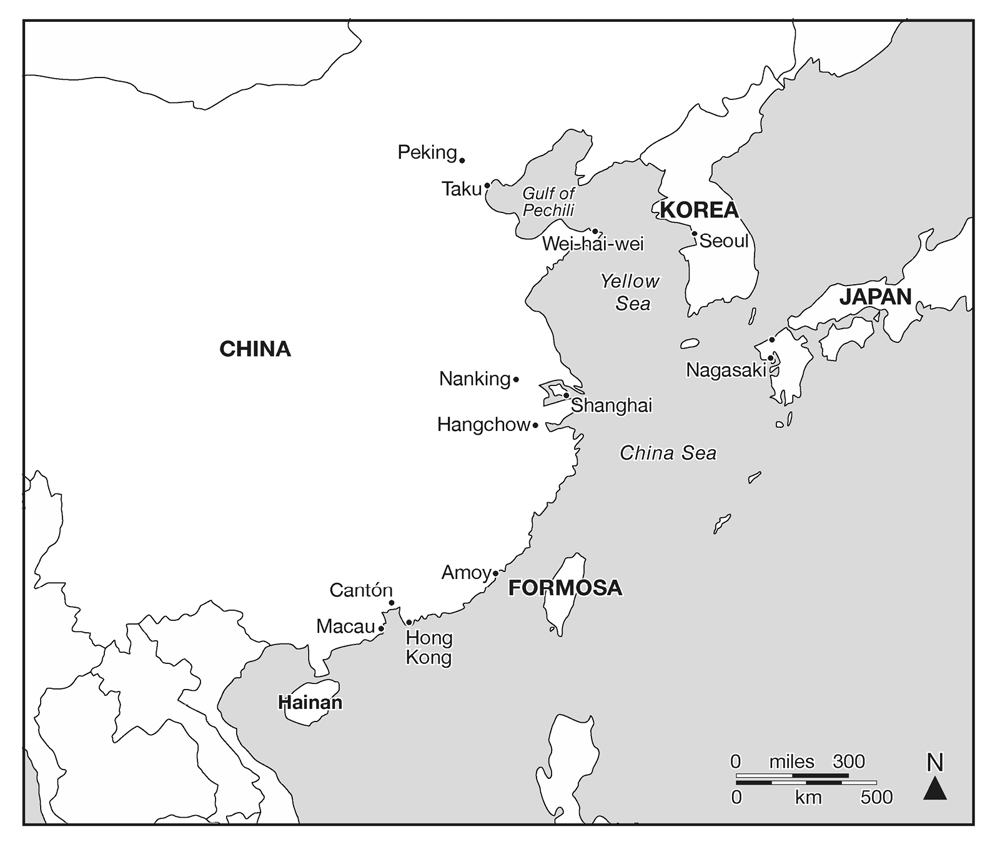

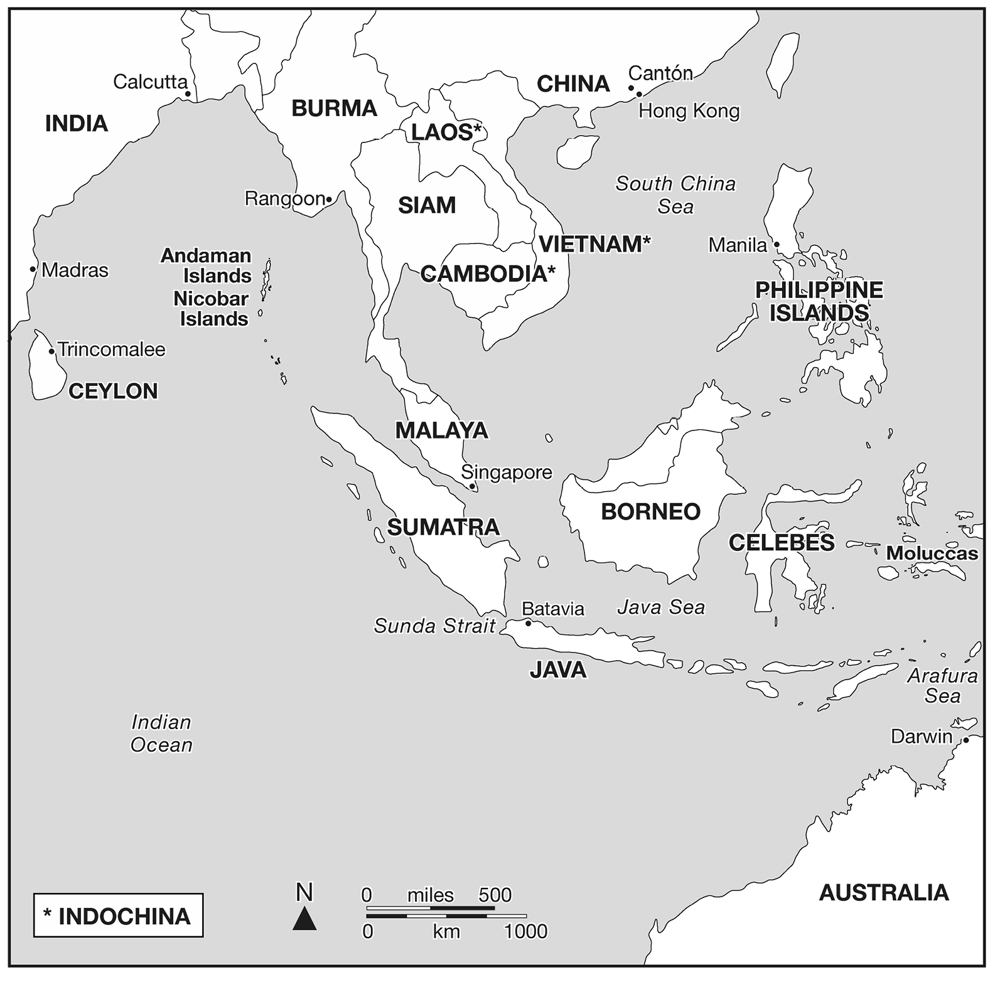

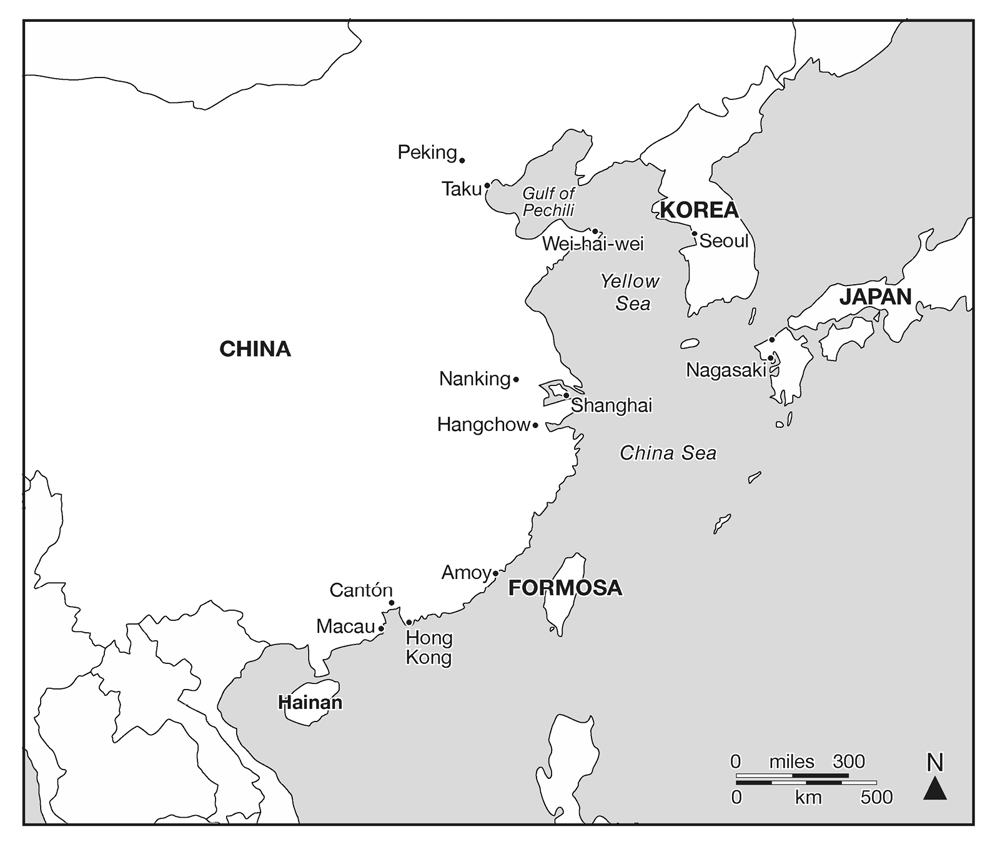

Map 1. The Western Indian Ocean.

Map 2. The Eastern Indian Ocean.

Map 3. The South China Sea.

Editorial Conventions

Throughout I have distinguished the East India Company by referring to it as the Company, with an initial capital.

Warships are distinguished by their number of guns, e.g. (60), after the name; merchant ships of the Company by their tonnage, e.g. (600).

Introduction

The subject of this book is the activities of the British Royal Navy in the Indian and the western Pacific Oceans, that is, in over half the world, from the Cape of Good Hope to China and Japan. Neither of these oceans and the lands they gave access to were known to European before the Age of Discoveries, though they were well enough known to many inhabitants of these regions, and certainly rumours and hints had reached Europeans of their existence. It was, of course, difficult for any European ships to penetrate into these oceans even in the century or so after the initial Portuguese explorations had reached them. This was in contrast to the accessibility of the contemporary revelation of the American continents, which seemed to be, by comparison, relatively easy to reach. It was clearly possible for English, French, and Dutch ships to get across the Atlantic and to interrupt Spanish activities in the Caribbean, and perhaps in West Africa and Brazil, but to reach the Pacific Ocean or the Indian Ocean required a voyage of years, far more courage and endurance, and a greater financial investment, than was involved in sailing to the east coast of America.

It was not at first known whether this could be done at all. Vasco da Gama, following Bartholomew Diaz and a long list of earlier Portuguese sailors, reached the Indian Ocean in 1498. The Portuguese had been moving slowly down the coast of Africa for a century before then, and had established a precarious control over the coast and its trade from Morocco southwards. R.S. Whiteway, The Rise of the Portuguese Power in India, 2nd ed., London 1967; Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Improvising Empire: Portuguese Trade and Settlement in the Bay of Bengal, 15001700, Delhi 1990.

Equally, to reach the Pacific by sailing westwards one had first of all to evade the Spaniards and the Portuguese, and then find a way round the long American double-continent. Numerous attempts sent out from Britain had failed in searching for a North-West Passage north of America, or a North-East Passage north of Asia, so the only recourse was to go south, where a passage through the American continent did exist, known since the time of Magellan, and another, somewhat easier, in the Southern Ocean, past Cape Horn. But the passages were fearfully difficult, the Cape Horn Passage was the scene of great storms, and the Magellan route led into the largest ocean in the world, where the prevailing winds and currents perversely took ships clear of all, or almost all, the islands where refreshment could be obtained. Magellans voyage was the archetype; most later voyagers followed his route and suffered much the same fate; J.C. Beaglehole, The Exploration of the Pacific, 3rd ed., London 1966, ch. 2; O.H.K. Spate, The Spanish Lake, Minneapolis 1979.

For a century after the discoveries of the 1490s and after, therefore, the Spaniards and the Portuguese largely had these oceans to themselves, without any serious interruption to their trading and conquering from other Europeans. But it was this very success in trading and conquering (and looting) which alerted other Europeans to the possibilities of also getting rich. Mexican and Peruvian silver, spices from the Indonesian islands, riches from India and Japan and China all these were quite sufficient temptation for European sailors to risk the wrath of Spain and Portugal, a long voyage in an unhealthy ship, and the strong possibility of death at any time, from disease, battle, storm, or starvation.

And so the first English sailor to reach the Pacific, Francis Drake, did so with the express intention of looting his way along the Spanish coast of western America, and the first English expedition into the Portuguese Indian Ocean, commanded by James Lancaster, fought his way into that ocean, attacking Portuguese ships wherever he found them. See chapter 1. The cost of such behaviour as it turned out, was very great, in sailors lives and in ships: although Drake returned rich, Lancaster did not. Between them they lost six ships and the great majority of their crews. And yet it was Lancasters voyage, and its apparent failure, which was the inspiration for the next stage in the British exploitation of eastern waters. The real value of these two voyages, and the circumnavigation by Thomas Cavendish in the 1580s, was to show that the voyages could be done, even at great cost, and, by returning, they brought back valuable information about the oceans and the lands surrounding them.

Cavendish had set out to emulate Drake, which he did as far as the Pacific coast of Mexico. There he captured the Manila Galleon, released the crew, and took his pick of the cargo before burning the ship. He also kept a few of the galleons passengers, two Japanese, a Filipino, and the Spanish pilot, and took them back across the Pacific. He travelled by a more northerly route than Drake, reached and refreshed at Guam Island, inspected the Philippines, and returned home, like Drake, by way of the Indian Ocean. Between them these three voyages had revealed several possible routes of entry into the two oceans for their successors to follow.

Drake, Lancaster, and Cavendish were not, of course, in the Royal Navy, if such a term can be used at this time, though the first two fought against the Armada in 1588. And yet all these voyages did have a semi-official air about them, as Drakes reception and knighting by Queen Elizabeth at Greenwich on his return demonstrated; the follow-up to Lancasters voyage, more productively, was the foundation of the East India Company, which, like Drakes exploit, was a semi-official organisation from the time it received its Royal Charter, through which the Company claimed a monopoly on trade by the English in its chosen region. This was granted by the English government, and the Company was linked very closely with the foreign affairs of England, and later Britain, from the start Spain and Portugal (linked in a single monarchy at the time) were active enemies in these years. Indeed, the Company later became an actual and overt official organ of the British government, which only emphasised the situation as it already existed, but hardly changed it. It seems therefore reasonable to begin this account with these three mens voyages (chapter 1). Their successors, as did these men, used their guns to gain access to trade which was blocked, where possible, by the Portuguese.

Next page