First published 2020 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Murray Armstrong 2020

The right of Murray Armstrong to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 4132 3 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 4133 0 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0656 7 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0658 1 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0657 4 EPUB eBook

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

For Cath

Acknowledgements

This book owes a great deal to the helpful professionalism of the staff at the National Archives in Kew, the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland, both in Edinburgh, the British Library in London and the London Library. The combined resources of these institutions, on their shelves and online, are formidable research tools. My thanks also goes to Mary Dunne of Airdrie Public Library and Karen Gallacher of the North Lanarkshire Archives in Motherwell for assembling so many valuable local documents for me to read.

A special thanks is due to Anne Beech, commissioning editor for Pluto Press, who had faith in this story and stuck with it for many months, as well as Jeanne Brady, who did such a speedy and accomplished edit of my manuscript.

1

1820: Death on the Green

The two women left their hiding place and crossed the burial ground to the newly dug grave. In the clear light of a waning August moon, they struggled to shovel away the loose sods and soil until they were waist deep. The blade of a spade struck the coffin. They hesitated before scraping the earth from the rough wooden box and forced open the lid as silently as they could. The bloodstained handkerchief covering the decapitated head was all the identification needed. It was the hanky James Wilson had dropped earlier that day to signal to the hangman he was ready to meet his end. After the hanging, a masked and cloaked axeman severed the head from the lifeless body, held it up to the thousands watching, and called out This is the head of a traitor!

Murder! Murder! they roared, He has died for his country!

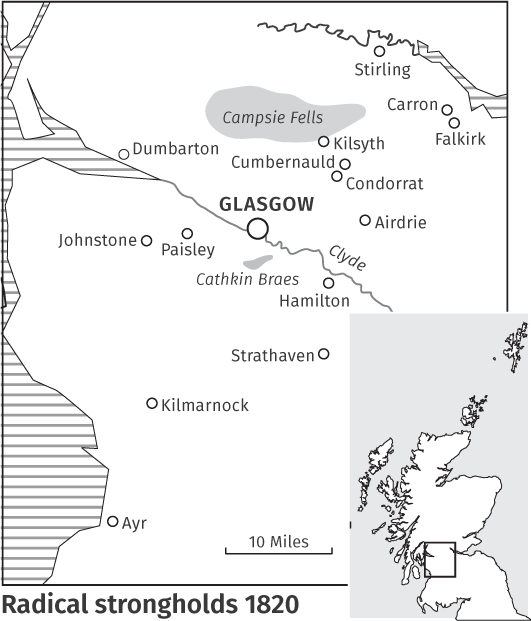

Lillian Walters grabbed a handle on her fathers coffin while her cousin, Mrs Ritchie, and two helpers who had arrived with a horse and cart, took the others. They hauled the heavy casket from the ground and manhandled it to the wall, where they lifted it over and placed it on the waiting cart. They left the paupers ground, under the walls of the ancient cathedral and, shortly after midnight, drove down Glasgows deserted High Street towards their home town of Strathaven. They passed the high clock steeple of the town hall at the cross and their silence seemed to intensify as they continued south on Saltmarket and neared the new courthouse and jail at the entrance to Glasgow Green. This was where, at 3 oclock that afternoon, the 63-year-old Wilson, dressed in white prison clothes, was executed for treason in front of 20,000 onlookers. The authorities were anxious on account of public sympathy shown for the old radical and had the scaffold and surrounding streets protected by a regiment of infantry with loaded muskets, reinforced by mounted and heavily armed dragoon guards.

Wilson had requested that his body be taken home and buried in the churchyard behind his cottage, and his daughter and niece had come to Glasgow in mourning clothes that day to witness his end and to supervise the transport of his body home. This was common practice after an execution, but in Wilsons case the authorities insisted he be buried without ceremony somewhere in the city. Some understanding official had, however, passed a hint to the family that the coffin would not be too difficult to recover, so friends in Strathaven organised a farmers cart and the two women hid in the shadows of the cemetery before it was closed and locked. It was 4 oclock in the morning before Lillian Walters, Mrs Ritchie, and their two friends reached the outskirts of Strathaven, where a large number of townsfolk, with their heads uncovered, accompanied them to the churchyard behind the Wilsons cottage and laid him in an unofficial grave, which remained unmarked for more than two decades because of opposition from local ministers.

Wilson had been condemned for taking part in a rising called by a provisional government. On 1 April 1820, posters appeared on the streets of towns and villages across the west of Scotland appealing to the inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland to take up arms for the redress of our common grievances and some 60,000 people in the five counties surrounding Glasgow downed tools in a general strike in support of the demand.

Petition after petition asking for an extension of the vote and reform of outdated constituencies and rotten boroughs had been rejected by parliament since the first popular movement for universal male suffrage in 1792. Wilson had been a member of the Scottish Friends of the People at the time and had attended a radical convention in Edinburgh in 1793 where he represented the reformers of Strathaven who were mostly, like him, weavers. That organisation was crushed and its national leaders prosecuted for sedition and transported to the new penal colony of Sydney Cove in Australia. Wilson was instrumental in keeping democratic ideas alive through more than twenty years of war with France, when political liberties were restricted and national organisations banned. At the end of the war in 1815, he campaigned against the newly introduced Corn Laws, which kept the price of bread high for the benefit of landowners, and he joined the renewed movement petitioning for parliamentary reform.

On the day after his death, the Glasgow Chronicle, which dismissed the 1820 radicals as A handful of poor, ignorant, presumptuous mechanics, without principles, without abilities, without funds or leaders, or a digested scheme of operations, nevertheless credited Wilson with being a good neighbour and a useful obliging man; and though a wag, and possessed of a fund of humour he conducted his drollery so as seldom to offend. He was a free thinker on religious subjects who sometimes went to church, but was more attached to Tom Paines criticism of organised religion, The Age of Reason. The Tory Glasgow Herald was more circumspect. On Friday, 1 September, it declared, By one set of people he is said to have been an easy-tempered man, led away by others, and it is with equal confidence asserted on the other hand that he was a man of bad morals, and of the worst principles in respect both of religion and of politics. His warmth was remembered by a friend, Margaret Hunter. I kent Jeems Wilson lang afore he was a prominent Radical, she recalled in 1887 at the age of 96. He was a noble weever, and mony a time made stockings and drawers for my guidman. He was often in oor hoose in Kilbride, and had dinner with us twenty times. He was highly respeckit a roun the kintra side.

The Political Union societies set up after the Napoleonic Wars, which advocated radical reform, were designed for education and discussion, and Wilson was class leader in Strathaven, most meetings taking place under his roof. By 1819, the gatherings in his house were discussing the English radical press, such as the