Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The majority of the photographs come from private collections. Others are from: , National Archives. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright but the publisher welcomes any information that clarifies the copyright ownership of any unattributed material displayed and will endeavour to include corrections in reprints.

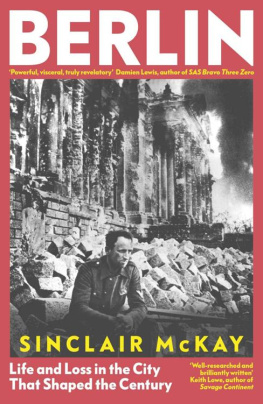

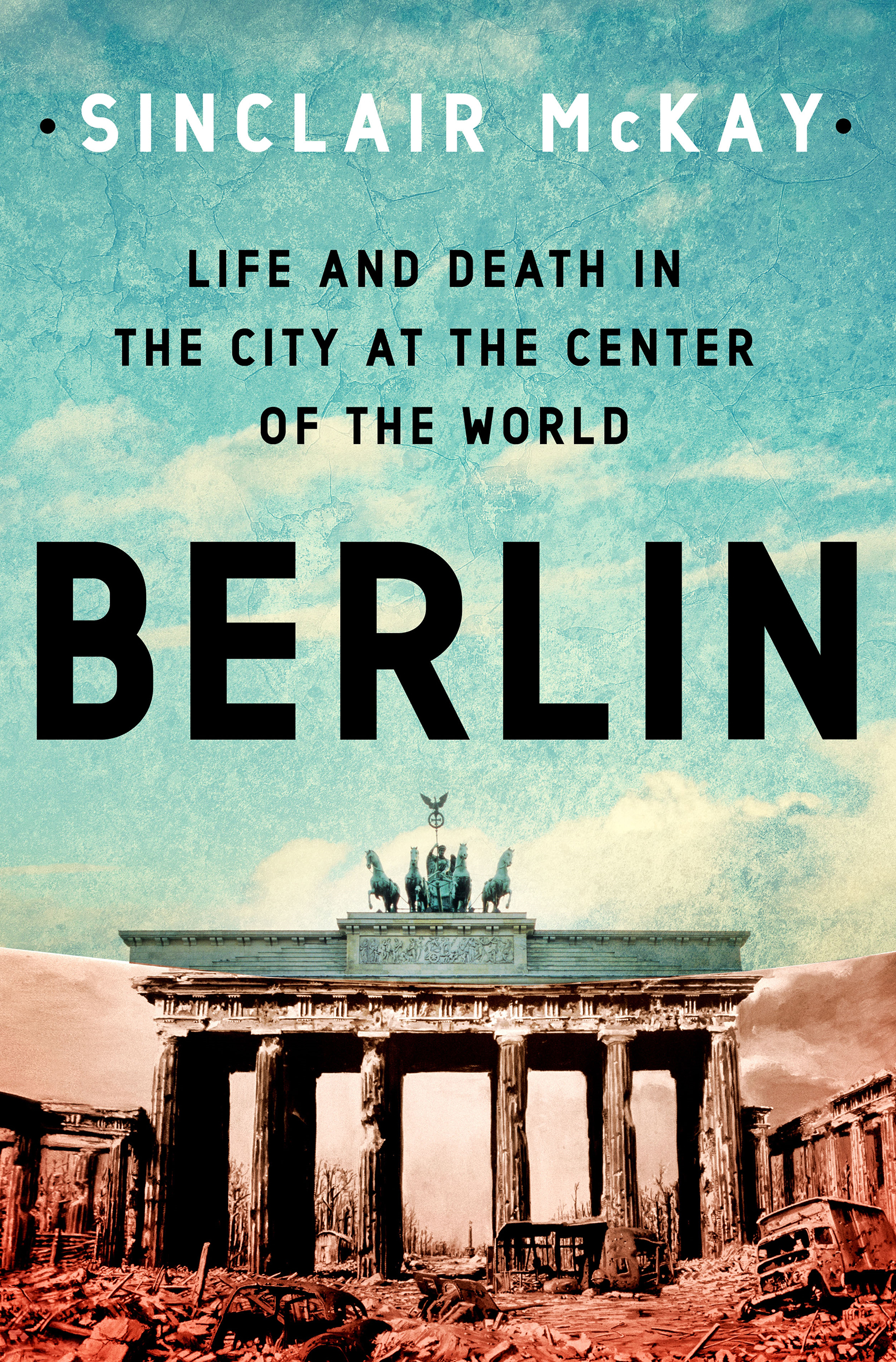

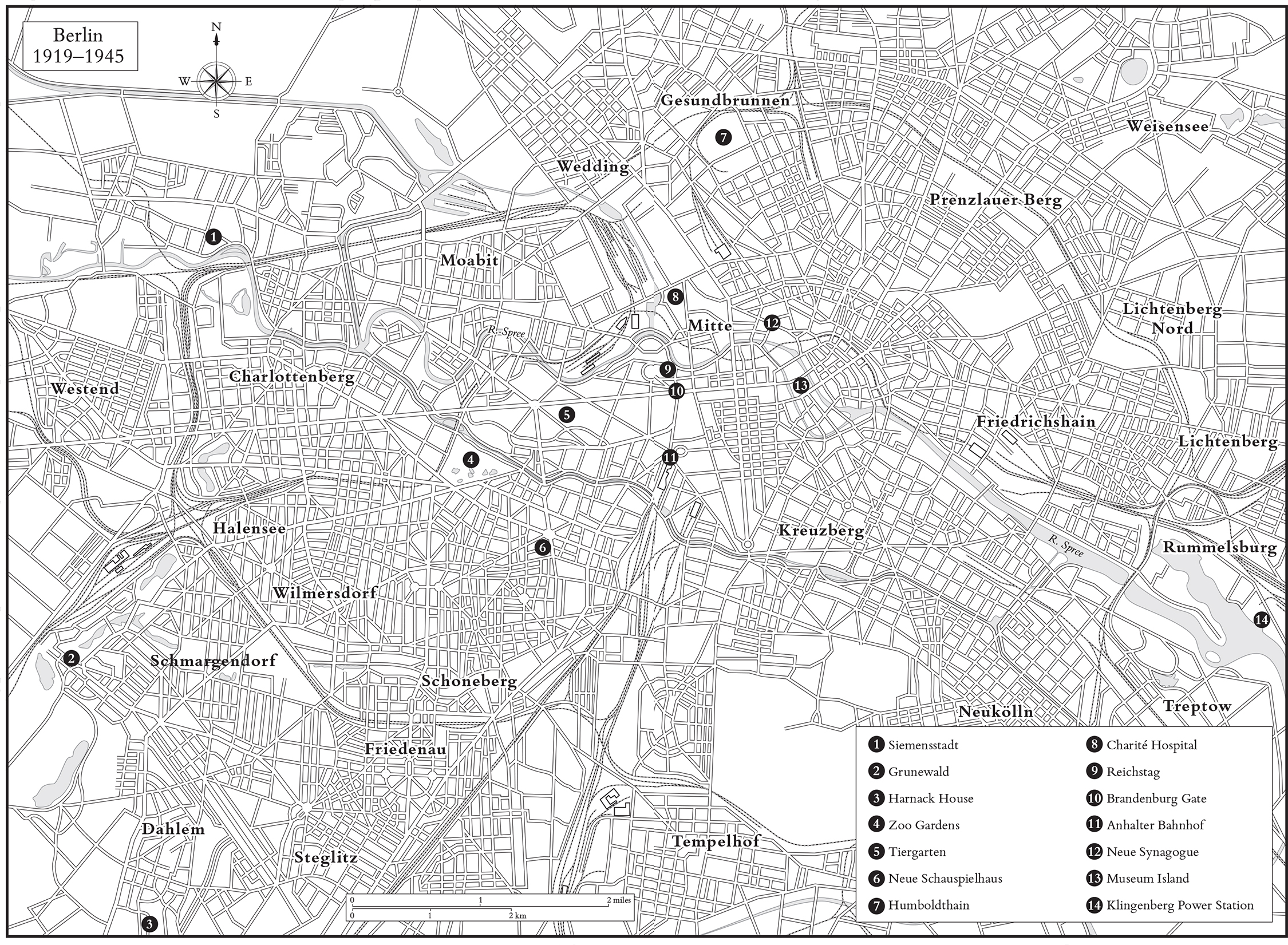

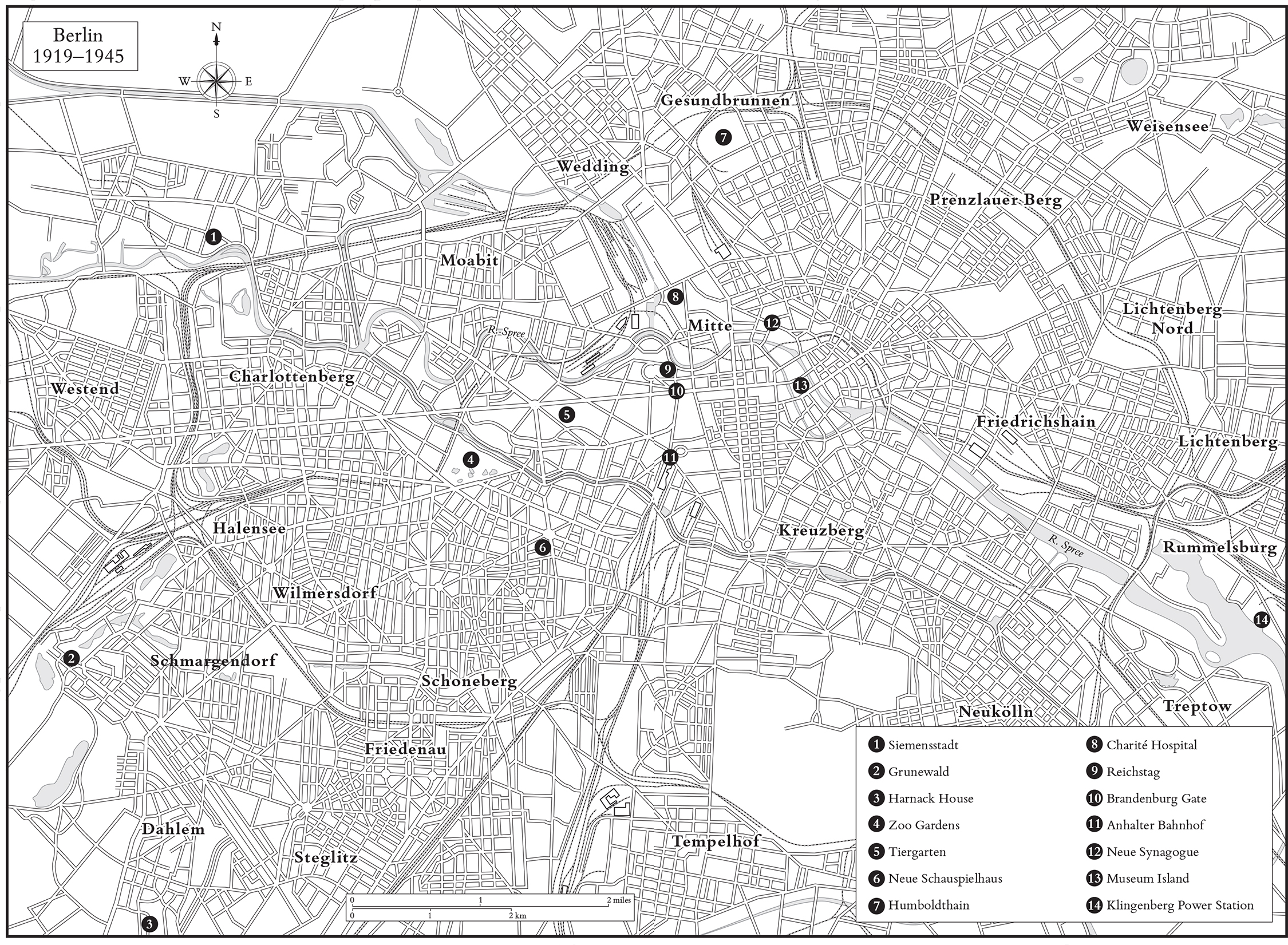

Berlin is a naked city. It openly displays its wounds and scars. It wants you to see. The stone and the bricks along countless streets are pitted and pocked and scorched; bullet memories. These disfigurements are echoes of a vast, bloody trauma of which, for many years, Berliners were reluctant to speak openly. In the shadow of filthy genocide, it was taboo to suggest that they too were victims in Hitlers war. The city itself is long healed, but those injuries are still stark: the old Friedrichsruhe brewery wall with a sunburst blast-pattern caused by heavy shelling; the bas-relief at the base of the nineteenth-century Victory Column, of Christ on the cross, pierced by shrapnel through the heart; the entrance portal to the bomb-crushed Anhalter railway station Romanesque brick arches now standing alone and leading only to empty air. In the Humboldthain, a rich park just north of the city centre, trees spring forth around a grim, vast, concrete fortress that, towards the end of the war, served as shelter, hospital and catacomb. Most famous is the shattered church tower, capped with metal, that stands over the busy Kurfrstendamm shopping street: the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. The tower is almost all that remains of the turn-of-the-century original; one night in 1943, it was hit in a bombing raid and engulfed in flames (and, after the war, a new hexagonal modernist church was constructed next to it). If you knew nothing of the history of this city, the initial sight of this strange tower would be disconcerting: what could be meant by this weird ruin preserved in the midst of an indifferent shopping concourse? Other European capitals acknowledge the dark past with elegantly aestheticized monuments; they seek to smooth the jagged edges of history. Not here.

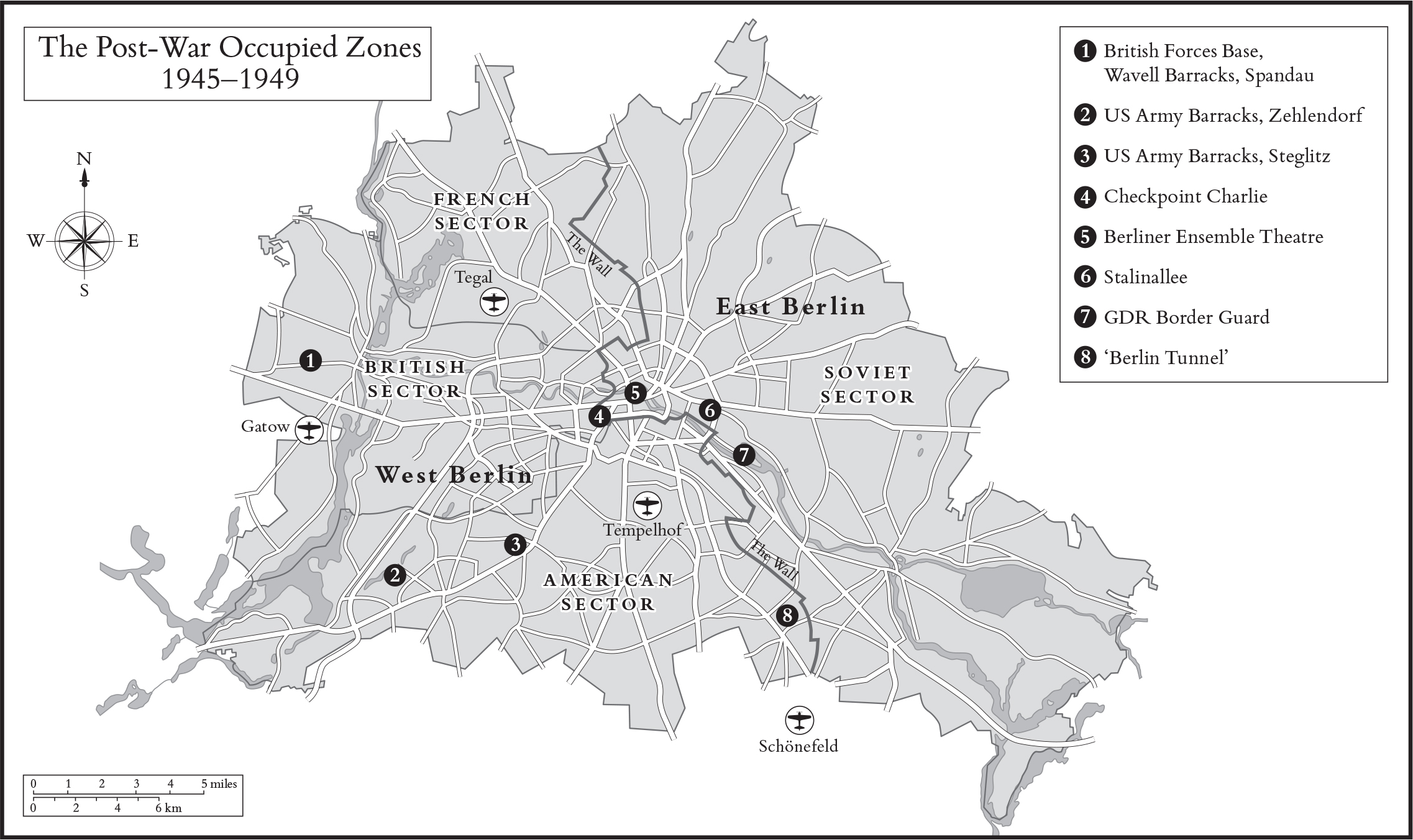

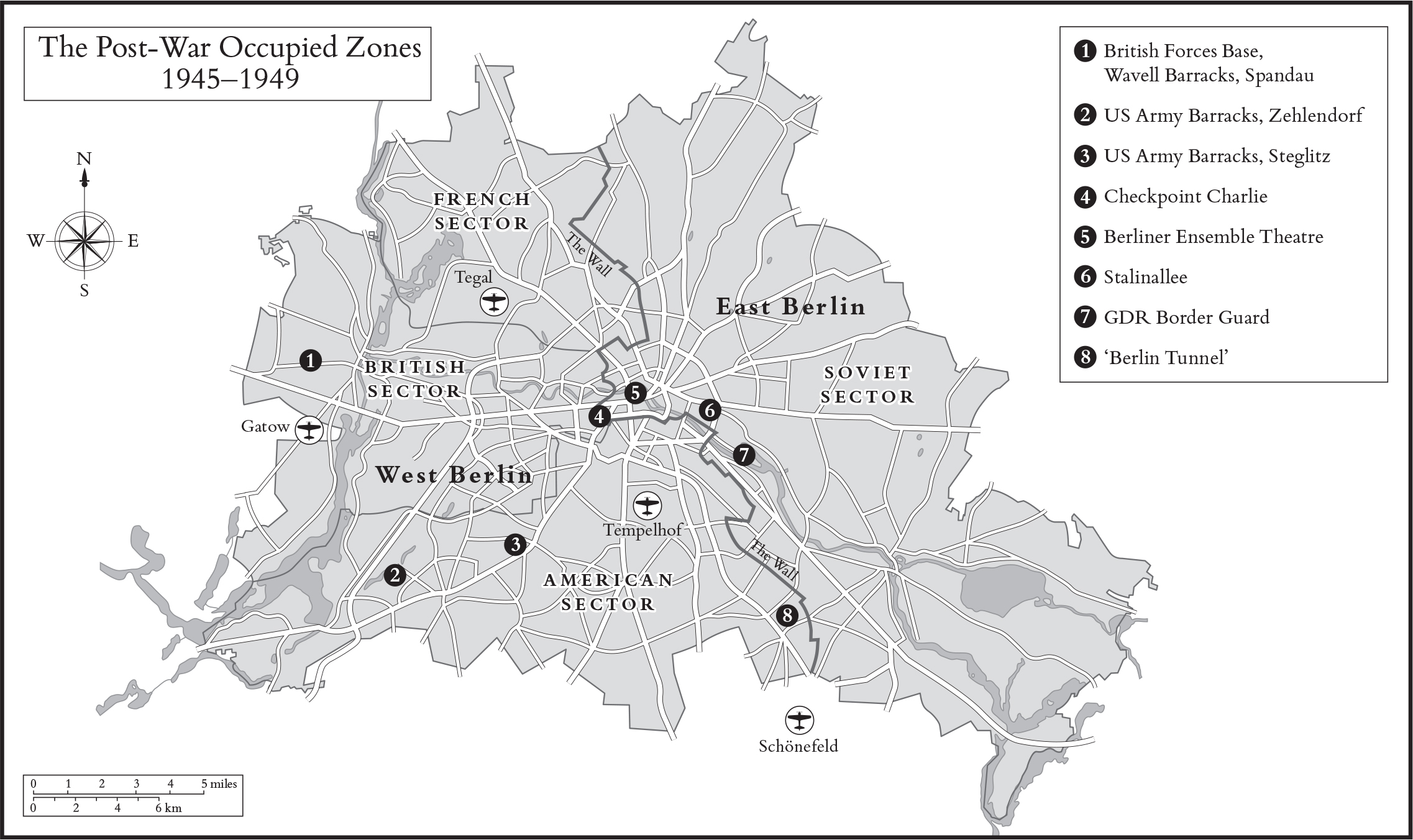

Throughout the twentieth century, Berlin stood at the centre of a convulsing world. It alternately seduced and haunted the international imagination. The essence of the city seemed to be its sharp duality: the radiant boulevards, the cacophonous tenement blocks, the dark smoky citadels of hard industry, the bright surrounding waters and forests, the exultant pan-sexual cabarets, the stiff dignity of high opera, the colourful excesses of Dadaist artists, the grim uniformity of mass swastika processions. And with the advent of the Nazis came a steadily building drumbeat of death. Of the citys Jewish population, most of those who had remained in Berlin under the Nazis 80,000 people or so were deported and murdered between 1941 and 1943. In addition, an estimated 25,000 Berliners were killed by Allied action in the final weeks of the war in 1945. But there was a continual proximity to fear, before and after, too: for anyone born in Berlin around the year 1900 and who was then lucky enough to live on into the 1970s or 1980s life in the city was an unending series of revolutions; a maelstrom of turmoil and insecurity. This spanned the reeling trauma of the First World War and the disease and violence that immediately followed; the sharp, vertiginous inrush of modern industry and the defiantly revolutionary architecture that mirrored it, roaring through once familiar streets and workplaces; the nausea of steep economic plunges, bringing destitution and hunger; then, the Nazi supremacy, the psychosis of genocide and the fires of war; and, finally, the heart of the city rent in two by competing ideologies. At the centre of these traumas were those weeks at the end of the war in spring 1945 when the devastation visited upon Berlin and its people was comparable to the infernal retributions of classical antiquity.

The city does not lack for heartfelt tributes to the dead: the exquisite and recent Holocaust memorial, a maze of monoliths that rise further over your head the deeper you move among them, is one of the few sites where the nervy pace of the Berliner is forcibly slowed. A few streets away from here is the much older, pale-stoned neoclassical Neue Wache memorial, built in 1818 in the aftermath of years of terrible European conflict. In recent times its purpose has been widened, and it has been transformed into a striking hall of commemoration to victims of war and dictatorship, the light pouring down through a circular hollow, or oculus, in the roof. But, for Berlin, the singular cataclysm of Hitlers war and the destruction wrought upon the city can never be easily memorialized. In the spring of 1945, as the Americans and the British fought through Germany, and as their bombers shattered ever more streets and tenements, turning homes to ash, and the vast Soviet forces closed decisively around the city, their screaming projectiles piercing the air, ordinary Berliners were prisoners facing inescapable horror. It was carnage for which the world had no pity. The city became a battleground that spoke of the final obscenity of total war. The tokens of civilization were crushed into dust, and Berliners were forced into a scavenging existence that strained at the threads of human nature.

And there was a further element of anguish in 1945, one that transcended the bombs and the mortars that left unburied bodies beyond recognition, the epidemic of suicide as thousands of citizens chose to end their own lives rather than submit to an enemy that filled them with terror, even the wholesale rape in literally uncountable numbers that created decades of family trauma across the city. It was the fact that these violations and cruelties were regarded by the implacable wider world as being understandable a final whirlwind of vengeance as unstoppable as nature itself. The Nazi leadership had inflicted agony and death upon millions across Europe. Berlins once-substantial Jewish community was terrorized for years before being expelled and exterminated. So how could their Berlin neighbours presume to tell the world that they too had suffered atrociously? This atoning silence left a bewildering cloud of moral ambiguity over the city. How total was the totalitarianism of the Nazis here?

The fall of Berlin in 1945 is one of those moments in history that stands like a lighthouse; the beam turns and sharply illuminates what came before and what came after. It was not just the squalid death of the man at the centre of the maelstrom, or the way in which his self-destruction in an underground bunker appeared to seep out and dissolve the foundations of the city itself. Nor is it a story that can be wholly understood as military history, since it is also a vast tapestry of ordinary civilian Berliners greatly outnumbering the remaining soldiers who could no longer protect them and their efforts to cling to their sanity as their lives were dislocated. It is also the story of those who had seen the warning shadows of this violence in the years beforehand. There were older Berliners in 1945 who had been there in the aftermath of the Great War and the failed German Revolution of 1918; who had already edged their way down icy streets transformed into sniper-canyons; who had already known chronic food shortages and unrelieved cold. In 1919, a poster appeared all over the city depicting an elegant woman locked in a tango with a skeleton. Berlin, stop and think! Your dance partner is death! proclaimed its strapline. The poster, inspired by the poet Paul Zech, was about public health measures in the wake of war, yet it suggested a wider morbidity in the citys nature.