The majority of the photographs come from private collections.Others are from: , Deutsche Fotothek.Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright but the publisher welcomes any information that clarifies the copyright ownership of any unattributed material displayed and will endeavour to include corrections in reprints.

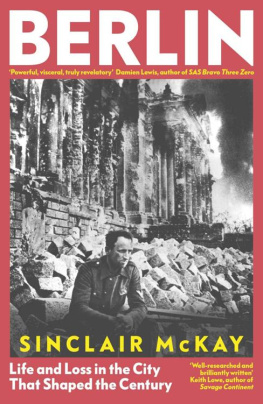

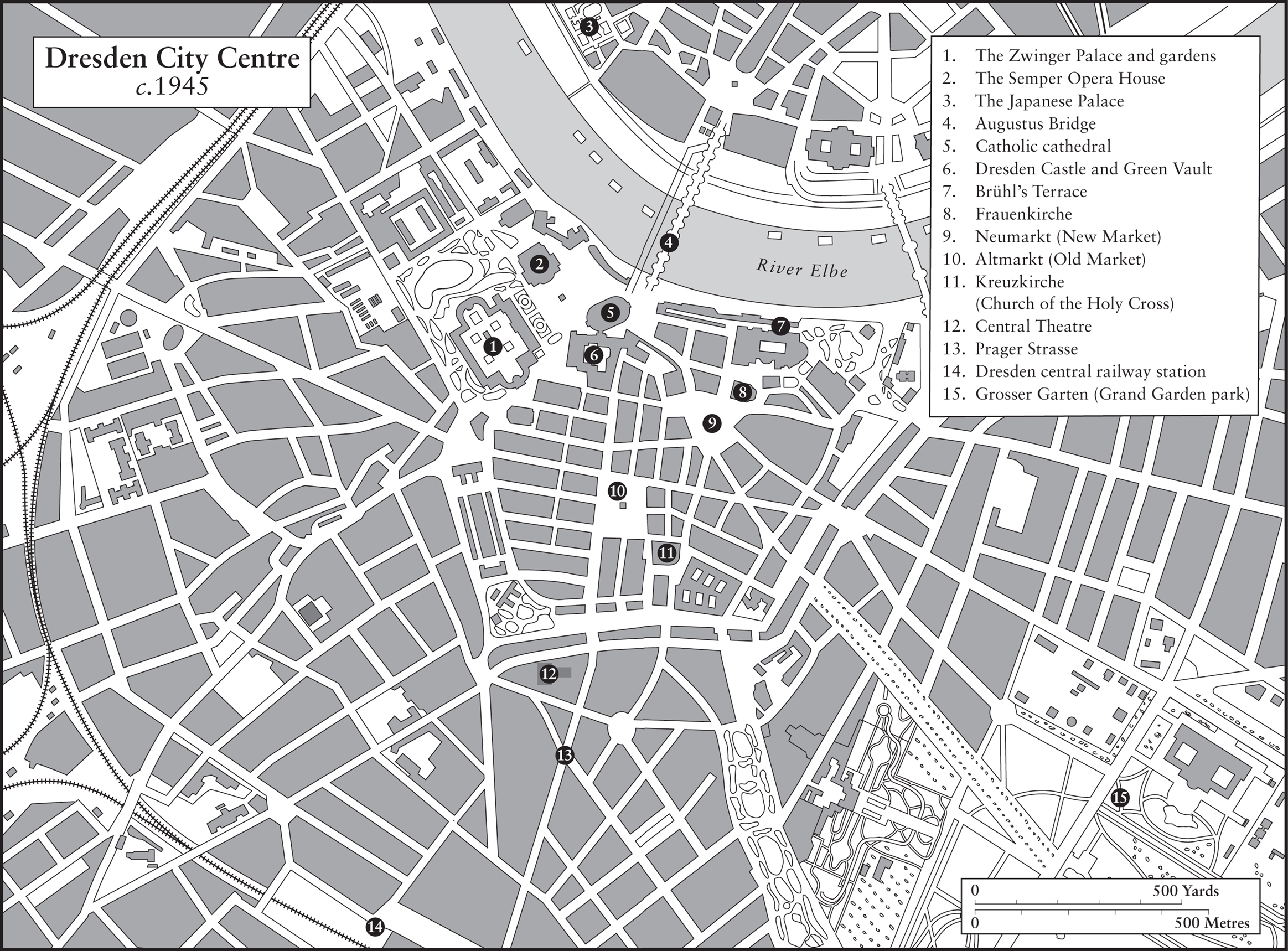

By the castle wall, and in the shadow of the Catholic cathedral, winter twilight can occasionally bring an arresting effect. If you glance around, it is possible, just for a fleeting moment, that you will find yourself alone. And here in this triangle of cobbled paving and sculptured stone the Schlossplatz, overlooked by the grand archway leading through to the castle courtyard, the church spire high and sharp against the amethyst sky time can smoothly slip its moorings.

If you are knowledgeable about the history of art, you might imagine yourself in the early nineteenth century, a figure frozen in a painting by the Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich, who lived in Dresden and depicted its steeples and domes, suffused in a lemon sunlight. You might allow yourself to roam yet further back: inhabiting a richly detailed Bellotto landscape. He too was drawn to the architectural elegance the wide market squares and beautifully proportioned houses and civic buildings of the city in the eighteenth century. Stand there long enough and there will be the music that those artists heard too: the bells of the cathedral. They strike, with some urgency, and clamour, and with a deeper, resonant note that sounds like anger.

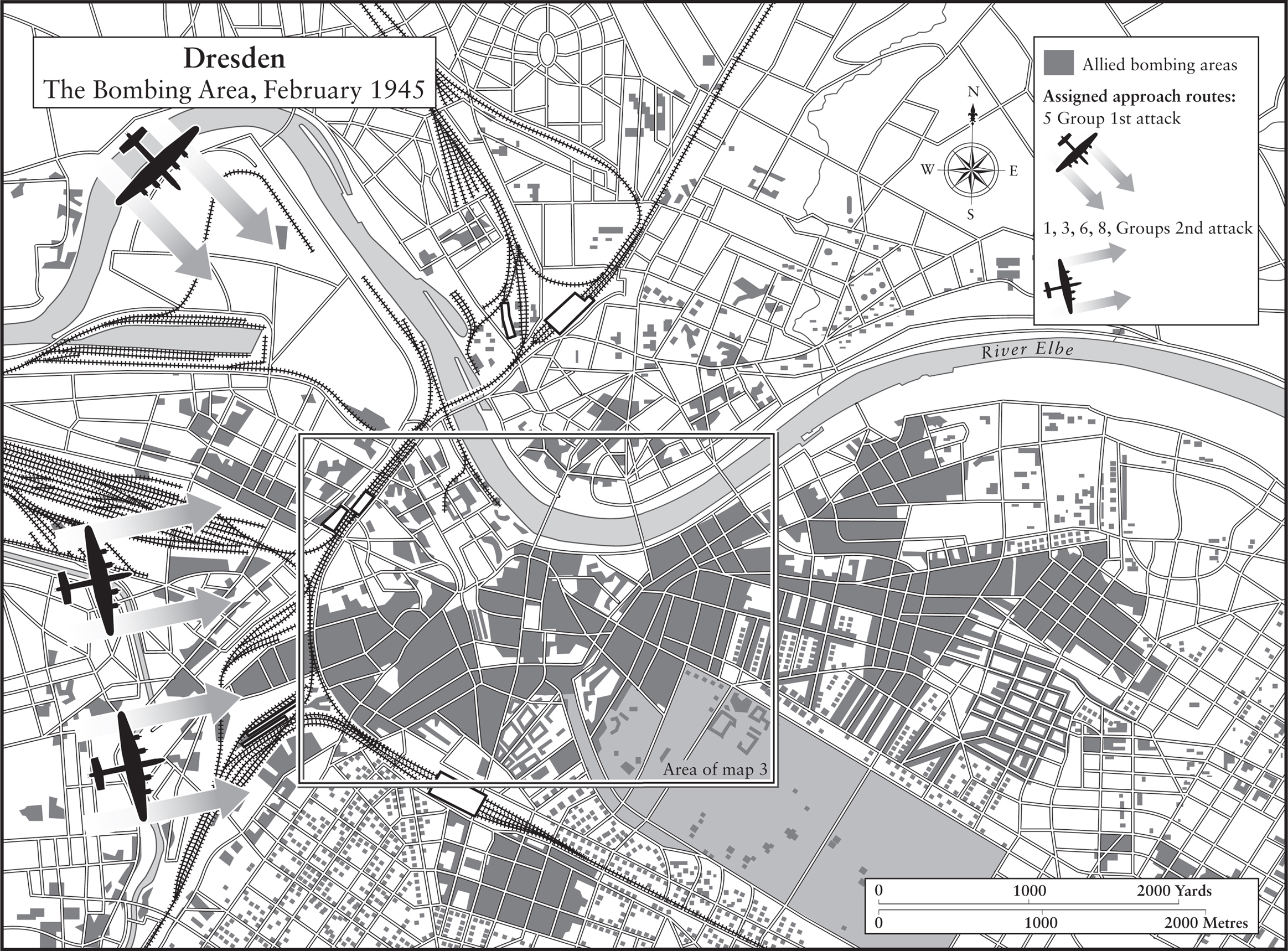

And it is in this near-discordancy that the more recent, terrible past is also summoned, unbidden; many who stand or walk here now, cannot help imagining, even for a moment, the bass drone of the aeroplanes overhead; the sky bright with green and red marker flares; and then roaring flames in the gutted cathedral rising ever higher.

Such visions are not confined to this one spot. Just a few yards from this square is the elegant terrace that overlooks the River Elbe and its curiously wide banks. Now, as then, this stone walkway stretches along to the Academy of Arts with its glittering glass dome. Just as with the Catholic cathedral, any stroll along here somehow takes place in two different time streams; you are there, in the present, gazing along the curving valley of the Elbe; and at the same time, you are seeing, against the clear cold night sky, the hundreds of bombers swooping in from the west. You envisage the terrified crowd of people around you, trying to escape the furnace flare heat, making as if by instinct for the river. This is the macabre truth of Dresden: every vision of beauty carries a split-second awareness of the most terrible violence. All visitors to this city will have felt that momentary dislocation. Unease would be the wrong word; the sensation is not ghostly. But there is a sharp cruelty about the juxtaposition of the fairy-tale architecture and the knowledge of what lies beneath it. And of course illusion is built upon illusion: for much of the fairy-tale architecture we see today was previously obliterated in the cataclysm.

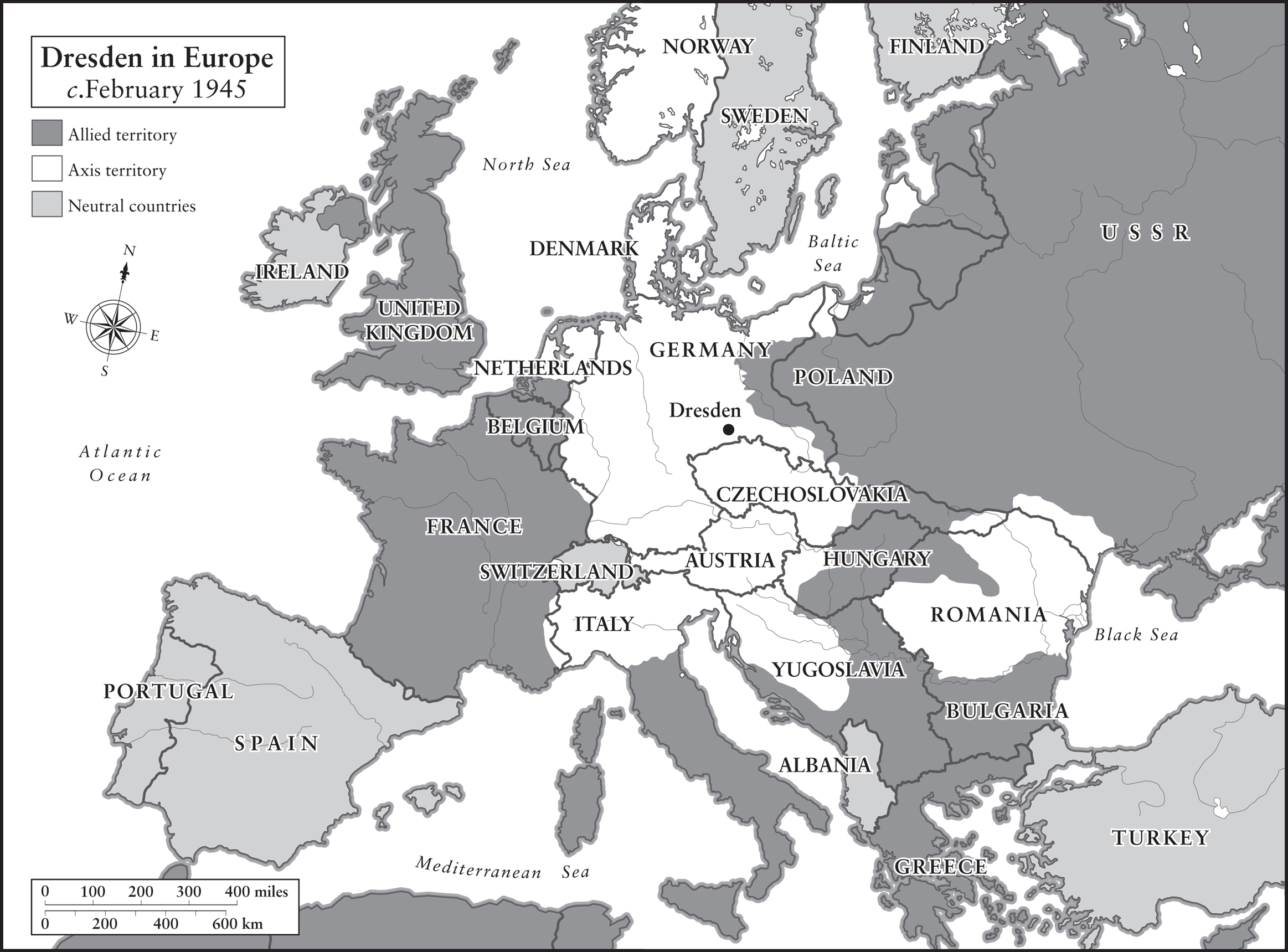

It should not be possible to see the city that expressionist artist Conrad Felixmller sketched so wittily in the 1920s; to gaze upon the stone and glass that Margot Hille seventeen-year-old apprentice brewery worker in the west of the city would have seen on her way home from work throughout the war in the mid 1940s; or to see the comfortable bourgeois world that Dr Albert Fromme and the Isakowitzes and Georg and Marielein Erler moved through at the beginning of the century the smart restaurants, the opera house, the exquisite galleries. It should not be possible to see any of these things because in just one night, on 13 February 1945, just weeks before that war ended, 796 bomber planes flew over that square, and that city, and in the words of one young witness, opened the gates of hell. In the course of that single, infernal night, an estimated 25,000 people were killed.

Dresden has been rebuilt, slowly, and not without difficulties and conflicts. The minutely detailed restorations have been married with sensitive modern landscaping, so that the new buildings on the market squares are not immediately obvious. But the curious thing is that despite the miraculous reconstruction, we can still somehow see the ruins.

In the case of the eighteenth-century baroque church the Frauenkirche, which overlooks the New Market square, this is deliberate: you are meant to see how the pale stone of the restoration rising high into the sky contrasts with the blackened original masonry, the shattered stumps of which were almost all of what was left after the pilots of Bomber Command and then, the following day, the US Eighth Air Force flew over.

The city stands now as a sort of totem to the obscenity of total war: like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Dresden is a name associated with annihilation. The fact that the city lay deep in the heart of Nazi Germany, and indeed had been an enthusiastic early adopter of the foulest National Socialist politics, added knots of extraordinary moral difficulty.

Across the decades, the stark morality (and immorality) of both the city and the act of destroying it with fire have been debated and analysed, with varying degrees of anger, remorse, pain and trauma. Such arguments are still very much part of the landscape. In Dresden, the past is in the present, and all have to tread carefully through these layers of time and memory.

An additional knot of difficulty lies in the citys more recent past: after the war, Dresden was subsumed into the German Democratic Republic, under the control of the Soviet Union. The Soviets took command of history, in the most literal sense; and the Soviets built new structures in the centre of the city that were supposed to reach out to the future. In the wave of continent-wide celebration that greeted German reunification in 1990, there were and still are a few who very sincerely regretted the collapse of the East German government.

One of Dresdens more celebrated citizens Victor Klemperer, an academic who was one of the very few Jewish inhabitants left after most others had been deported to death camps remarked after the war that the city was a jewel box; and that was one of the chief reasons the firestorm commanded so much attention. It is certainly the case that other German cities and towns proportionally suffered more; Pforzheim, in the west, was attacked a few weeks after Dresden and the percentage of the population who were killed in the space of just a few minutes was higher than even the extraordinary number of fatalities in Dresden.