ALSO BY MARSHALL DE BRUHL

Sword of Jacinto: A Life of Sam Houston

Copyright 2006 by Marshall De Bruhl

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

All photographs, with the exception of the image of the reconstructed Frauenkirche, are from the collection of the Schsische Landesbibliothek-Staats-und Univerittsbibliothek Dresden/Abt. Deutsche Fotothek. Photographers are listed with their individual works.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALO GING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

De Bruhl, Marshall.

Firestorm: Allied airpower and the destruction of Dresden/by Marshall De Bruhl.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76961-9

1. Dresden (Germany)HistoryBombardment, 1945.

I. Title.

D757.9.D7D4 2006 940.542132142dc22 2006041059

www.atrandom.com

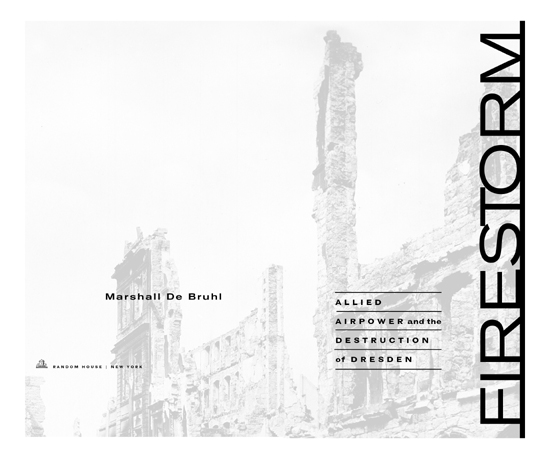

Title-page photograph, Mathildenstrasse, by Paul Winkler, Stadtmuseum, Dresden, 1945

v3.1

FOR BARBARA

PREFACE

D uring a visit to the coast of France in the summer of 1984, I found myself standing on a platform at the top of a stairway that led down to a beach. It was a beautiful day, warm and sunny. From far below I could hear the squeals of children splashing in the mild surf, young men shouting to one another as they kicked a soccer ball around, and, occasionally, music being borne along on the slight breeze.

It was a very different scene from that of four decades earlier, when the sounds coming from the beach below were those of one of the most desperate struggles of modern times. For this was Normandy and that place was Omaha Beach.

I was on my own pilgrimage, just a few days after thousands of veterans and world leaders had come to this site for the fortieth-anniversary celebrations of the Allied invasion. I was just a boy in a small town in North Carolina when the Allies landed here to free Europe from the Nazis, but I vividly remember how my family gathered around the radio in our living room and listened to the live broadcasts from the landing sites.

My thoughts that morning in June 1984 were of the cousins and uncles who had been with the invasion force. One of them, an infantry officer, saw his promising professional baseball career ended by a German bullet in the left lung. Another, the executive officer of a paratroop unit, was killed just a few days after landing behind the beachescoincidentally, not far from where his father was killed in World War I.

My sad but proud reflections were interrupted by the laughter of a young woman and two young men who were making their way up the long stairway from the beach. As they reached the landing where I stood, the girl suddenly exclaimed, My God. What is this place? The three of them fell silent.

Spread out before them in perfectly ordered rows were the 9,387 marble Christian crosses and Stars of David of the United States Military Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. Most of the men buried there were about the ages of these young people when they died on the beach below, or fighting their way up the very same steep bluff, or during the bloody advance inland after D-day.

Those young people had come to spend a few hours at the beach, not to visit a battlefield or a war memorial, but they listened attentively to my brief but emotional account of the Normandy invasion, of which they knew nothing. It was as distant to them as the wars of ancient Greece. They then quietly took their leave to wander among the graves.

The ravages of the Second World War are hardly to be seen today as one travels through the cities and countryside of Europe. There are war memorials to be sureobelisks, vast monuments to the dead, eternal flames, and in some cities the hulk of a burned-out building left untouched as a reminder to the passersby that something terrible happened here over a half century ago.

Most Americans, however, are so inured to seeing cities being torn down and rebuilt that they are like those carefree students on their holiday. They seem not to be aware, or much care, that the lovely beaches, the beautiful orchards and vineyards, and the rolling fields of France and Belgium and Germany were once soaked with the blood of hundreds of thousands of young men.

For a truer picture of the carnage of World War II, one must look to the cities, not the battle sites, which, often as not, now resemble well-tended parks. The healing power of nature is evident in the countryside. Vines, wildflowers, and grasses cover the shell holes and bomb craters. Bones of unknown war dead still work their way to the surface or are accidentally turned up by plows and spades, and hapless farmers still occasionally fall victim to the random unexploded shell or land mine long buried in the soil. But instead of ravaged farmlands and the lanes and byways ripped up by the passage of thousands of tanks and trucks and armored vehicles, the fields are much as they were before total war came to these bucolic regions.

Man-made structures can be restored and reconstituted only by other men, however, not by nature. And it was the urban environmentwith its villas, houses and palaces, apartment blocks, factories, government buildings, churches and cathedrals, schools, and shopsthat was the scene of the greatest devastation. This sort of destruction could never be imagined until the twentieth century and the birth and development of a new form of warfare.

This new war bypassed the armies clashing in the field. It was waged hundreds, often thousands, of miles from any battlefront. This campaign was against the civilian population, which, as war has become more brutal, has increasingly become the target and borne the brunt of military operations.

In the great cities of Germany, visitors are largely oblivious to what predated the ubiquitous glass towers, the pedestrians-only shopping areas, and the almost too wide streets and expressways. To be sure, many historic structures, indeed whole areas of cities, have been reconstructed exactly as they were. But prewar urban Germanythat congested, vibrant, thousand-year-old architectural museumwas washed away in a rain of bombs and could never be wholly reclaimed.

For some cities, such as Berlin, the rain of fire was constant, day after day, night after night. But for one city, there had been only two raids in the more than five years that Germany had been at war. Both had been relatively minor attacks, so the people of Dresden were lulled into that false security that is often a prelude to a great disaster. When their storm came, it was a firestorm, and the destruction and death were on a scale not hitherto imagined in warfare.

The Dresden raid, on 1314 February 1945, by an Anglo-American force of over a thousand planes, has been a source of controversy, debate, and denial for six decades. It is one of the most famous incidents of the war, yet one of the least understood. It has led to rumors and conspiracy theories, to wrecked reputations, and to charges of war crimes. And it is another reason for the question that has been asked millions of times after the battlefields have been cleared, the wounded gathered up, the dead buried, and the monuments raised. It is a simple question: Why?

The Dresden story is one with particular relevance to our own era. The moral issues presented by war and, especially, aerial bombardment are timeless. The efficacy of bombing continues to be an article of faith among not only leaders of armies but leaders of nationseven though noncombatants, people far from the lines of combat, are most often the victims. In Germany, hundreds of thousands of civiliansmostly women, children, and old mendied as the cities were blasted away.