Contents

Guide

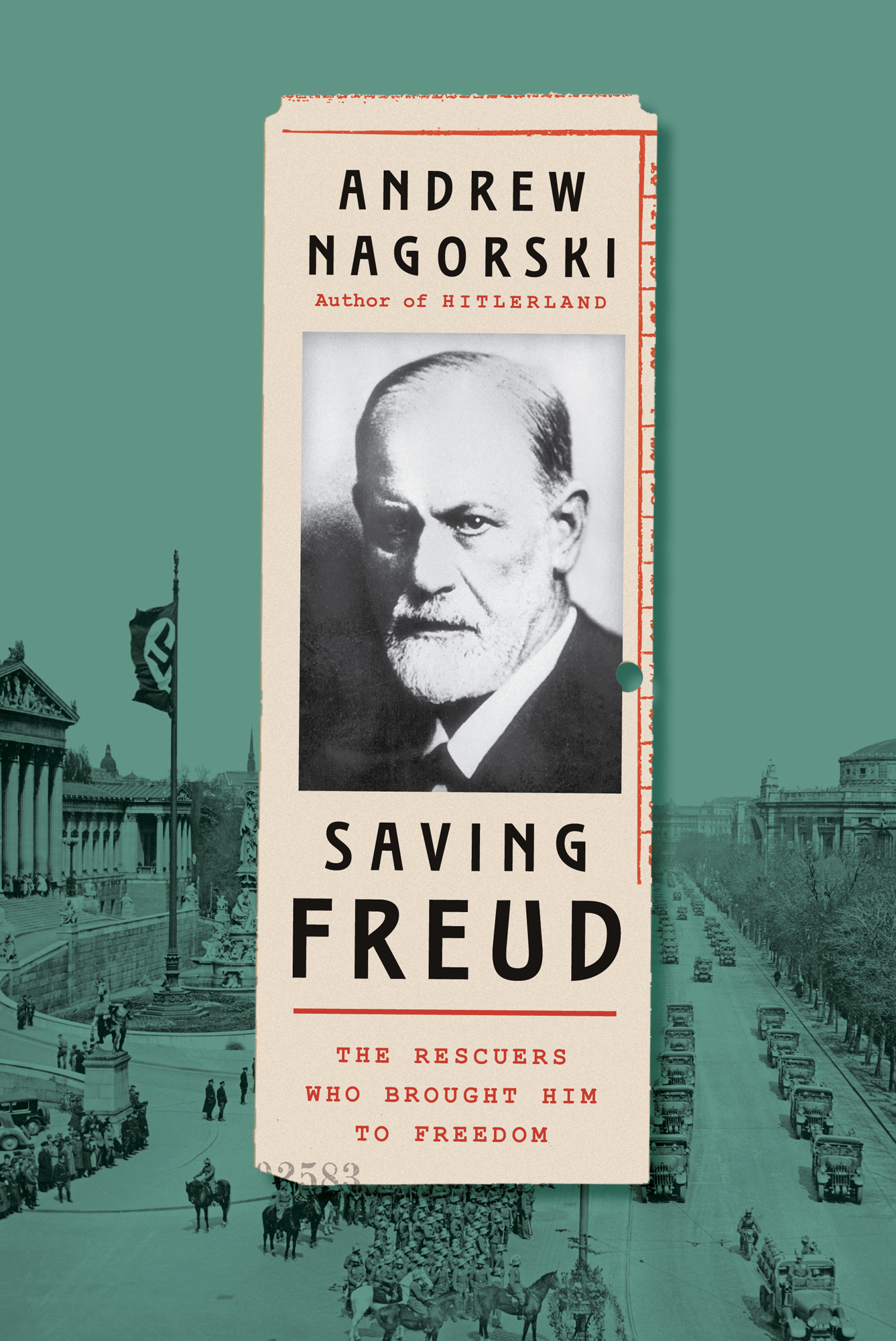

Andrew Nagorski

Author of Hitlerland

Saving Freud

The Rescuers who Brought Him to Freedom

For Isabel,

And, as always,

For Krysia

It is an iron law of history that those who will be caught up in the great movements determining the course of their own times always fail to recognize them in their early stages.

S TEFAN Z WEIG , The World of Yesterday

1. TO DIE IN FREEDOM

O N M ARCH 15, 1938 , THREE days after German troops had crossed into Austria, about 250,000 people greeted Adolf Hitler when he appeared on the balcony of the Hofburg, Viennas imperial palace, to announce the elimination of a separate Austrian state. The oldest eastern province of the German nation shall from now on be the youngest bulwark of the German nation, he declared. The Anschluss, his oft-proclaimed dream of incorporating the country of his birth into the Third Reich, was now a realityand the crowd appeared deliriously happy. From the moment Hitlers troops had marched across the border, most Austrians had responded with similar outbursts of jubilation.

But not all. The new arrivals launched mass arrests of anyone categorized by the Gestapo as anti-Nazi, while simultaneously triggering a wave of anti-Semitic violence. Jews were beaten and killed, their stores looted, and dozens committed suicide. According to German playwright Carl Zuckmayer, who was in Vienna at the time, The city was transformed into a nightmare painting by Hieronymus Bosch What was unleashed upon Vienna was a torrent of envy, jealousy, bitterness, blind, malignant craving for revenge It was the witchs Sabbath of the mob. All that makes for human dignity was buried.

Ensconced in his longtime residence and office at Berggasse 19, Sigmund Freud had written a terse note in his diary as soon as the German takeover began: Finis Austriae (the end of Austria). For all but the first four years of his life, the founder of psychoanalysis had lived in the Austrian capitaland now, as he was approaching his eighty-second birthday, he found himself right in the middle of the unfolding nightmare. As a Jew, he was automatically in danger; as the undisputed public face of what most Nazi officials denounced as a Jewish pseudoscience, there was no telling what the new masters had in store for him.

Freud was an immediate target. On the same day that Hitler delivered his speech nearby, Nazi thugs invaded both Freuds apartment and the International Psychoanalytic Press, the publishing house for the works of Freud and his colleagues, which was situated just up the street at Berggasse 7. At the apartment, Freuds wife, Martha, had the presence of mind to throw the visitors off balance by playing the polite hostess. She pulled out the cash she had on hand and asked, Wont the gentlemen help themselves? Anna, the couples youngest daughter, then took their guests to another room where she emptied the safe of 6,000 shillings, the equivalent of about $840, offering that sum to them as well.

The stern figure of Sigmund Freud suddenly appeared, glaring at the intruders without saying anything. Visibly intimidated, they addressed him as Herr Professor and backed out of the apartment with their loot, announcing they would return another time. After they left, Freud inquired how much money they had seized. Taking the answer in stride, he wryly remarked, I have never taken so much for a single visit.

But there was nothing amusing about the unfolding drama there or, nearby, at the site of the International Psychoanalytic Press, where Martin, the Freuds oldest son, had gone to destroy documents that the Nazis could use against his father. When about a dozen shabbily dressed thugs burst into the premises, as Martin recalled, they pressed their rifles against his stomach and held him prisoner for several hours. One of the men ostentatiously pulled out a pistol and shouted, Why not shoot him and be finished with him? We should shoot him on the spot.

During that chaotic first day, the invaders looked confused about their mission and it was unclear who was giving them orders. They missed several documents that Martin, while pleading a stomach ailment, managed to flush down the toilet. By the end of the afternoon, all of the Nazis retreated, promising a full investigation later.

Back at the apartment, where Martin joined his parents and sister, there was little sense of relief. Anna was especially despondent. Wouldnt it be better if we all killed ourselves? she asked her father. Freuds pointed response indicated that he was not about to contemplate anything of the sort. Why? Because they would like us to? he said.

But his predicamentwith its very uncertain outcomeraised troubling questions: Why had Freud allowed himself to be trapped in this extremely perilous situation? Why had he failed to leave Vienna earlier when it would have been relatively easy for him to do so?

And why, even after the Nazi raiders left his premises on March 15, vowing to return soon, was Freud still reluctant to act? Once Martin was released from the publishing house, he had immediately gone home to check on his parents. In spite of this trying ordeal, I do not think father had yet any thought of leaving Austria, Martin wrote. Instead, he hoped to ride out the storm, expecting that a normal rhythm would be restored and honest men permitted to go on their ways without fear.

The irony was that Freud should have been uniquely qualified to understand the dark forces propelling his world to mass murder and destruction. In his famed 1930 essay Civilization and Its Discontents, he discussed mans aggressive cruelty, which manifests itself spontaneously and reveals men as savage beasts to whom the thought of sparing their own kind is alien. He specifically noted how often Jews had rendered services to others by serving as the outlet for such primal impulses.

During a life that spanned the last decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, World War I, and the interwar period, Freud was no stranger to political turmoil and anti-Semitism, which was less of an undercurrent than a regular feature of his immediate surroundings. On one level, he knew that this made for a combustible mix that could explode at any time, threatening him and his family. But on another level, he was in denial. He was struggling with the cancer that had developed in his jaw as a result of his long addiction to cigar smoking, and he was acutely aware that his allotted time was running out, prompting him to hope desperately that he could spend whatever was left of it in relative peace, without the upheaval of settling elsewhere.

It was more than the combination of old age and illness that was holding him back, however. Freud felt a deep attachment to the Vienna that had been a major center of culturaland Jewishlife in Europe for centuries. Its thriving Jewish community included composers like Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg, writers like Stefan Zweig, Franz Werfel, and Joseph Roth, along with physicists, physicians, and, of course, many of the other leading psychologists of the era. Freud knew or had at least encountered most of them.

The center of Freuds universe was Berggasse 19, where he and Martha had raised six children. It was also where he saw his patients, wrote his essays and books, and met on Wednesday evenings with the members of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association. He was wedded to rituals like his evening walks on the Ringstrasse and visits to the citys famed cafes, where he would smoke his cigars and read newspapers. In short, he was a revolutionary thinker who also subscribed to the German saying