Samuel J. Redman - Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums

Here you can read online Samuel J. Redman - Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

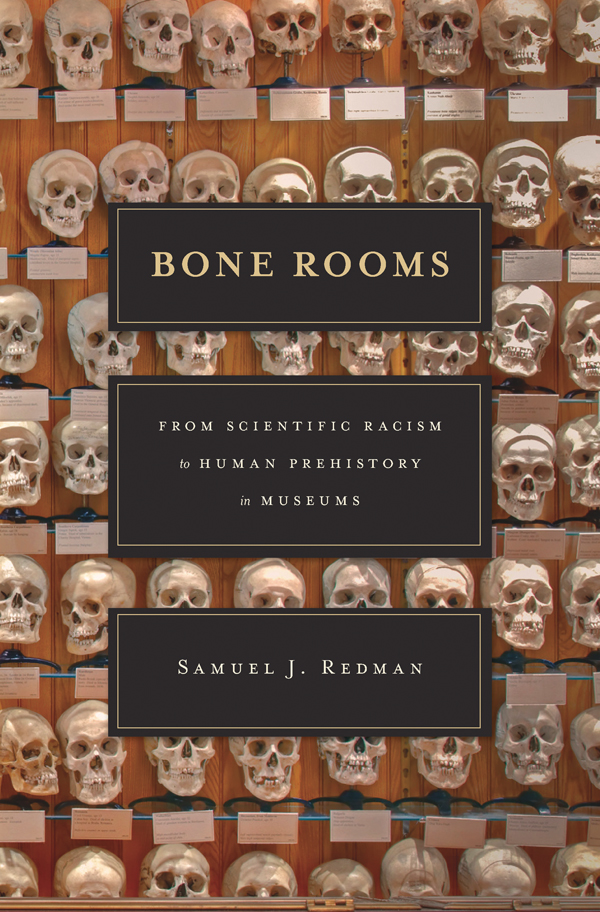

- Book:Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Smithsonian Book of the Year

A Nature Book of the Year

Provides much-needed foundation of the relationship between museums and Native Americans.

Smithsonian

In 1864 a US Army doctor dug up the remains of a Dakota man who had been killed in Minnesota and sent the skeleton to a museum in Washington that was collecting human remains for research. In the bone rooms of the Smithsonian, a scientific revolution was unfolding that would change our understanding of the human body, race, and prehistory.

Seeking evidence to support new theories of racial classification, collectors embarked on a global competition to recover the best specimens of skeletons, mummies, and fossils. As the study of these discoveries discredited racial theory, new ideas emerging in the budding field of anthropology displaced race as the main motive for building bone rooms. Today, as a new generation seeks to learn about the indigenous past, momentum is building to return objects of spiritual significance to native peoples.

A beautifully written, meticulously documented analysis of [this] little-known history.

Brian Fagan, Current World Archeology

How did our museums become great storehouses of human remains? Bone Rooms chases answers...through shifting ideas about race, anatomy, anthropology, and archaeology and helps explain recent ethical standards for the collection and display of human dead.

Ann Fabian, author of The Skull Collectors

Details the nascent views of racial science that evolved in U.S. natural history, anthropological, and medical museums...Redman effectively portrays the remarkable personalities behind [these debates]...pitting the prickly Ale Hrdlika at the Smithsonian...against ally-turned-rival Franz Boas at the American Museum of Natural History.

David Hurst Thomas, Nature

Samuel J. Redman: author's other books

Who wrote Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.