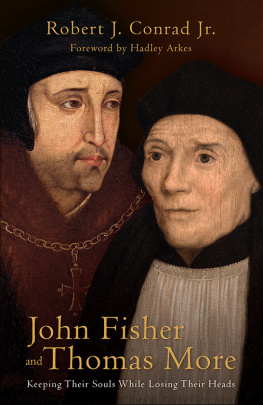

John Fisher and Thomas More

JOHN FISHER

AND

THOMAS MORE

Keeping Their Souls While Losing Their Heads

Robert J. Conrad Jr.

TAN Books

Gastonia, North Carolina

John Fisher and Thomas More: Keeping Their Souls While Losing Their Heads 2021 Robert J. Conrad Jr.

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in critical review, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from the Revised Standard Version of the BibleSecond Catholic Edition (Ignatius Edition), copyright 2006 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

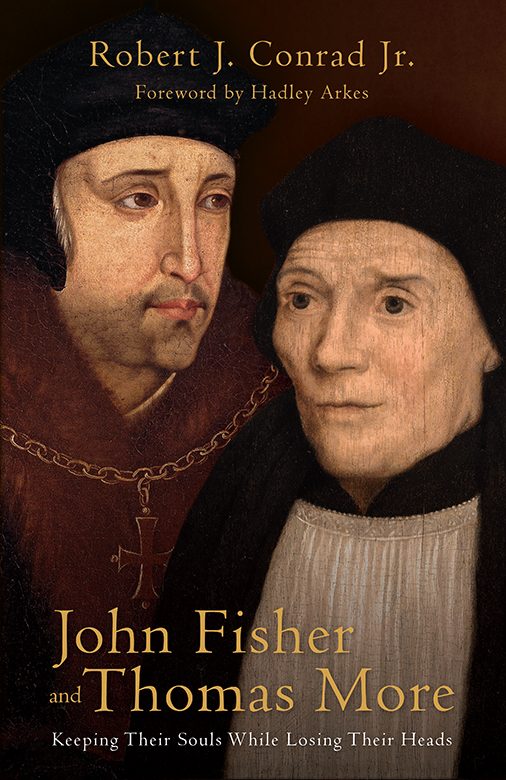

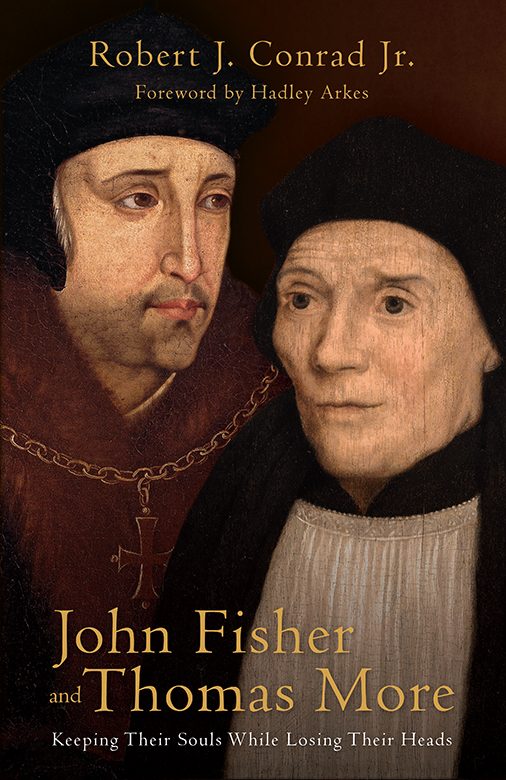

Cover design by Caroline Green

Cover images: Portrait of Saint Thomas More, painting by unknown Lombard author (17th century), Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana/Mondadori Portfolio / Bridgeman Images. Portrait of John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, mid-16th century (oil on panel), Holbein the Younger, Hans (1497/8-1543) (follower of) / Germa, Photo Philip Mould Ltd, London / Bridgeman Images.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021933062

ISBN: 978-1-5051-1849-0

Kindle ISBN: 978-1-5051-1850-6

ePUB ISBN: 978-1-5051-1851-3

Published in the United States by

TAN Books

PO Box 269

Gastonia, NC 28053

www.TANBooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

To my good friends KTK and RMG

Contents

T he remarkable John Fisher entered Cambridge at the age of fourteen; he was ordained a priest in 1491 at the age of twenty-two. Ten years later, he became vice chancellor, rising to chancellor of his beloved university in 1504. The same year, he was named the bishop of Rochester. He would be confessor to the mother of King Henry VII, and possibly also a tutor to the prince who would become Henry VIIIand order his execution.

Thomas More would become a distinguished figure in all branches of the English government of Henry VIII, rising finally to the highest executive position in the realm as lord chancellor. Still, he would be warned that the wrath of the king is death. To which he responded, Is that all my lord? Then in good faith, there is no more difference between your grace and me, but that I shall die today and you tomorrow. There is a rich story to be told about Fisher and More, but that one line offers an entry into the story that may prefigure everything else. For it enlightens the reader to understand just what there was in the moral formation of these men that made them willing to court death in response to a prince they had served, and go with serenity to their executions.

Of the legend of Thomas More so much has been heard, but far less attention has been given to Fisher. And yet Fishers story reveals a record of courage and conviction not any shade less than that of Mores. For they shared the same depth of faith that alone could explain why both men were able to move even cheerily to their executions. Their two stories are recalled now and woven together in the most telling way by Robert Conrad in this new bookand caught so aptly in his subtitle: Keeping Their Souls While Losing Their Heads. More remarked to the jurors who convicted him that we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together to our everlasting salvation. Later, he kissed his executioner and said, Thou will give me this day greater benefit than ever any mortal man can be able to give me. For his part, Fisher prepared calmly for his execution, he dressed in his finest clothes and told his servant that this was his marriage day, and it behooved him to dress for the solemnity of the marriage.

These stories offer a dramatic mix of law and theology, and Conrad brings to it the eye of a former federal prosecutor, now a senior federal judge in North Carolina. But he brings also the angle of a serious Catholic who takes his faith seriously, that same faith that removed from these saints the fear of death. The trials through which More and Fisher passed would not exactly pass a demanding test of due process of law in our own time. But Conrad leads us through the thicket.

For Fisher it began with Henrys move to divorce himself from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. A hearing was held at the Legatine Court, and Bishop Fisher served as counsel to the queen. When Catherine stood on her own to make her case, it was simple, powerful, and affecting. She had borne his children, including three sons who had died, and she asserted that at the time of their marriage, I was a true maid without touch of man. She pointed out that his father, King Henry VII, and her father, King Ferdinand of Spain, famous as wise and excellent counselors, believed the marriage was good and lawful. And finally, she reminded Henry that the pope had issued a bull confirming her marriage to be valid.

Even a gathering of tamed bishops could be chastened. Nevertheless, the fix was in. Henry declared that the bishops unanimously accepted his case, and the archbishop of Canterbury chimed in that all my brethren here present will affirm the same. But the moment was quickly broken when Bishop Fisher said, with firmness, No sir, not I. You have not my consent thereto. This simple but powerful response set him on the path to his execution.

More and Fisher refused to take the oaths confirming Henrys divorce, or to endorse the Act of Supremacy, establishing Henry as the Supreme Head of what was now the Church of England. More and Fisher fell back on the understanding in the law that silence implies consent. They made a claim to conscience as a way of showing the want of malice that was necessary to the crime. But silence, of course, would not do, and so the Act of Succession took their refusal to take the oath as the misprision of a felony. The refusal to take the oath would be regarded as a gesture of intransigence, and taken then itself as evidence enough to warrant imprisonment. Henry could not find his position settled and secure unless Fisher and More would be avowedly with himthat they would speak the telling words that cleared the air of moral doubt.

It is worth pausing to recall the sequence of legal measures brought forth by Henry and his willing aides. The first Act of Succession in March 1534 prohibited any malicious slandering by writing, print, deed, or act of the kings title. This act was followed by an oath of allegiance not only to the succession but also to the legitimacy of the kings marriage to Anne Bolyenand the illegitimacy, then, of his prior marriage to Catherine. The Act of Supremacy made the king the only Head of the Church of England on Earth so far as the Law of God allows. And the Treason Act that followed made it treason, punishable by death, to challenge the Act of Supremacy.

Fisher and More had held back in decorous silence from taking the oath to support Henrys divorce, and they refused to acknowledge the king as the Supreme Head of the Church. For refusing to take the oath following the Act of Succession, they were attainted in different bills. That is, they would be proclaimed guilty, by name, in an Act of Parliament, without one of those vexing trials that could test in a demanding way the guilt or innocence of these menand the statute under which they were imprisoned for life.

More and Fisher would fall back, even in their own minds, on the claims of conscience. But the notion of conscience has been the parent of serious confusion in this story. The most famous account of More has come through Robert Bolts play-turned-movie A Man for All Seasons. Bolt had More say that what matters to him is not that I

Next page