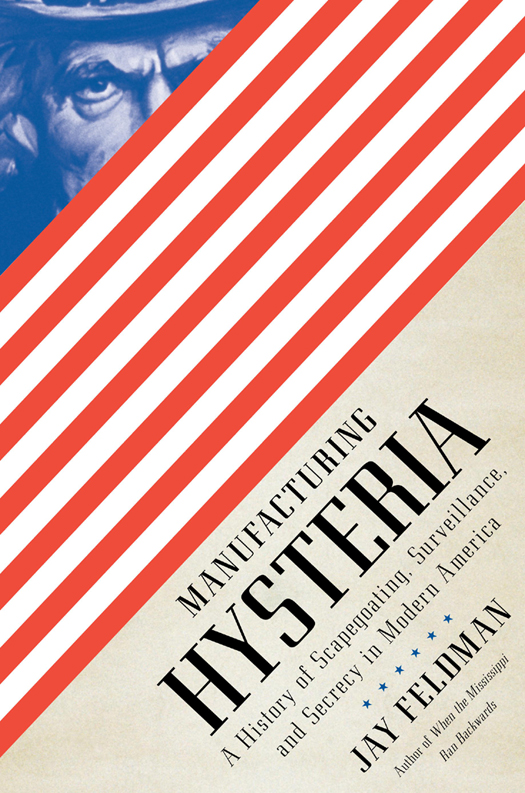

Jay Feldman - Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America

Here you can read online Jay Feldman - Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Pantheon Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America

- Author:

- Publisher:Pantheon Books

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jay Feldman: author's other books

Who wrote Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ALSO BY JAY FELDMAN

When the Mississippi Ran Backwards

Suitcase Sefton and the American Dream

Copyright 2011 by Jay Feldman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feldman, Jay, [date]

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37986-3

1. Civil rightsUnited StatesHistory. 2. DissentersUnited StatesHistory.

3. Marginality, SocialUnited StatesHistory. 4. Hysteria (Social psychology)

I. Title.

JC599.U5F415 2011 323.490973dc22 2010039998

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket image The Granger Collection, New York

Jacket design by Linda Huang

v3.1

To the memory of Howard Zinn

Democracy can come undone. Its not something thats necessarily going to last forever once its established.

Sean Wilentz,

Newsweek, October 31, 2005

On the night of April 4, 1918, nearly a year to the day after the United States entered World War I, a harrowing spectacle was unfolding on the streets of Collinsville, Illinois, a small market center and coalmining community of four thousand, located twelve miles across the river from St. Louis. Trailed by a roused and swelling crowd, a forlorn, barefoot figure wrapped in an American flag hobbled along in the cold night air. An occasional catcall rang out in the dark, and the threat of festive violence loomed heavily. The man at the head of the discordant parade stumbled frequently as the march made its way up the main street of Collinsville toward city hall.

The unfortunate leading this unsettling procession was Robert Paul Prager, a thirty-year-old German immigrant and, by some accounts, a radical Socialist. Born in Dresden, Prager had immigrated to the United States in 1905, at the age of seventeen. He bounced around the Midwest for several years, working as a baker, serving fourteen months for theft in 191314, and eventually finding his way, in 1915, to the St. Louis area, with its sizable, well-established German-American population. He worked for a time in a coal mine in Gillespie, about forty miles northeast of St. Louis, then headed to Collinsville in the fall of 1917, where he took a job in Lorenzo Brunos bakery.

According to Mrs. Bruno, Prager was extremely intelligent and an outstanding worker, but a certain peculiarity in his makeup made him quarrelsome with people who did not agree with his ideas on ways of doing things. Despite his ready inclination to apologize once his temper had cooled, Pragers argumentativeness led to his being fired early in 1918.

Turning to the only other work he knew, Prager got a job on the night shift at the No. 2 mine owned by the Donk Brothers Coal and Coke Company in Maryville, four miles from Collinsville. The leadership of United Mine Workers of America Local 1802 accepted him conditionally until his application for UMWA membership could be reviewed.

It was here that things started to go seriously wrong for Prager. Looking to improve his lot, he thought to become a mine manager. In late March, he approached the mine examiner John Lobenad and, informing Lobenad of his desire to advance, questioned him about a managers responsibilities. One of the areas he asked about was mine explosions, and exactly how an explosion could cause the greatest damage. Lobenads suspicions were aroused, and when rumorsutterly unsubstantiatedsuddenly began circulating about a supply of blasting powder vanishing from the mine, some of the six hundred miners at Donk No. 2, including the Local 1802 president, Joe Fornero, concluded that Prager was a German agent bent on sabotage.

In the hypercharged winter and spring of 1918, the mere suspicion of harboring pro-German sentiments, let alone actively working for Germany, was enough to invite the attention of federal, state, and local law-enforcement agencies, as well as a myriad of quasilegal vigilante organizations. Since entering the war, the federal government had whipped the American public into a froth with a calculated program of propaganda issued by the Committee on Public Information.

Headed by the newspaperman George Creel, the CPI utilized every available medium to sell the war to an initially skeptical citizenry. The committees job, as Creel wrote, was to drive home to the people the causes behind this war, the great fundamental necessities that compelled a peace-loving nation to take up arms to protect free institutions and preserve our liberties, and to weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct with fraternity, devotion, courage, and deathless determination.

Creel and his associatesincluding some three thousand historians recruited for pamphlet writingdid their job only too well, cultivating a hatred for everything associated with Germans and Germany. The press enthusiastically took up the chant. As one New York newspaper would put it, Scrutinized historically, and presented baldly, the German cannot be but recognized as a distinctly separate and pathological human species. He is not human in the sense that other men are Promoting anti-Germanism and love of country, the CPI infected the American public with a virulent strain of patriotism tinged with a streak of potent xenophobia. All dissenting voices on the war were, by implication, disloyal and therefore pro-German: pacifists, Wobblies, Socialists, anarchists, Mennonites, Irish-Americans, and above all, German aliens and German-Americans were some, but not all, of the tainted and suspect.

Throughout the country, scores of Germans came under attack. On December 22, 1917, Charles H. Feige, who had been taking photographs near the border in El Paso, tried to cross into Mexico and was shot and killed by a soldier, who assumed he was a spy.

On January 5, 1918, one Maximilian Von Hoegen was beaten, suffered a broken nose, and was forced to kiss the American flag in Hartford, Connecticut. The following week, Philadelphia police rescued a man named Paul Beilfuss from a lynch mob.

By the spring of 1918, the nation was in a patriotic frenzy. Reports of German spy networks and espionage filled the newspapers, with wildly exaggerated numbers of German agents supposedly operating in the country. On March 1, citing the Department of Justice as his source, the international president of the Rotary Club informed a Chicago audience that at least 110,000 German agents were operating in the United States. The number was never confirmed.

The next day, a Denver squad of loyal Americans tied Fred Sietz, by a rope around his neck, to a truck and paraded him through the streets. They delivered Sietz, who had refused to kiss the flag, to the office of The Denver Post, where he collapsed and was rushed to the hospital in serious condition.

On March 3, the senator and future president Warren G. Harding, speaking at a large patriotic meeting sponsored by the Maryland Council of Defense, offered his opinion that the only place for Germanys miserable spies is against the wall.

The violence escalated into the first week of April. On the second, in La Salle, Illinois, 150 miles from Collinsville, Dr. J. C. Bienneman was dunked in a canal, made to kiss the flag, and ordered to leave town. The same day, Rudolph Schwopke was tarred and feathered in Emerson, Nebraska, for allegedly refusing to contribute to the Red Cross.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America»

Look at similar books to Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Manufacturing Hysteria: A History of Scapegoating, Surveillance, and Secrecy in Modern America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.