This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1998 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War I

Army Air Forces Medical Services in World War II

James S. Nanney

Army Air Forces Medical Services in World War II

This history summarizes the Army Air Forces (AAF) medical achievements that led to the creation of the Air Force Medical Service in July 1949. When the United States entered World War II, our nations small aviation force belonged to the U.S. Army and relied on the Army medical system for support. The rapid expansion of the AAF and the medical challenges of improved aircraft performance soon placed great strain on the ground-oriented Army medical system. By the end of the war, the AAF had successfully acquired its own medical system oriented to the special needs of air warfare. This accomplishment reflected the determined leadership of AAF medical leaders and the dedication of thousands of medical practitioners who volunteered for aviation medical responsibilities that were often undefined or unfamiliar to them. In the face of new challenges, many American medics responded with hard work and intelligence that contributed greatly to Allied air superiority.

Lt. Gen. (Dr.) Edgar R. Anderson, Jr., USAF, MC. Ret.

U.S. Air Force Surgeon General (September 1994-November 1996)

INTRODUCTION

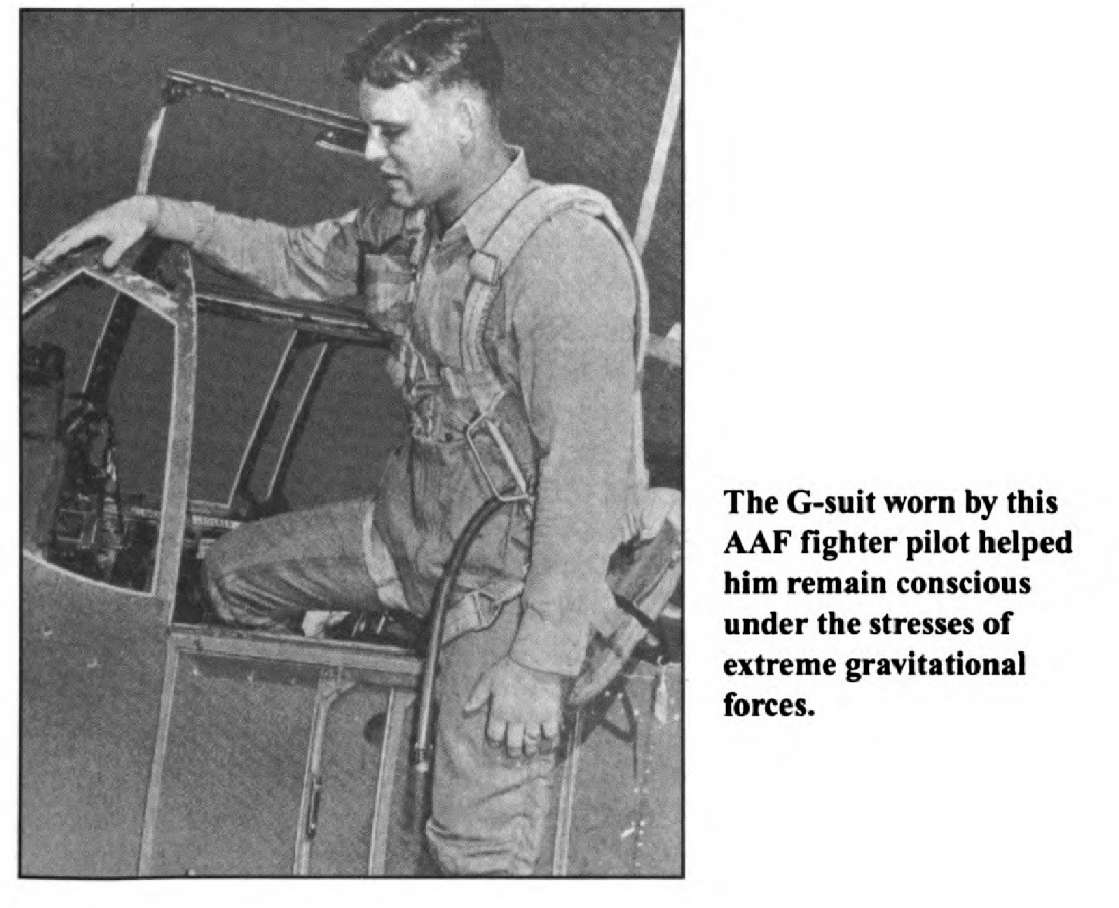

The Army Air Forces (AAF) relied on many types of medical support in World War II. One of the greatest medical contributions was research and development of personal survival gear and equipment for fighter and bomber crews. AAF doctors, for example, helped design the first flying suits that countered the physiological effects of the excess gravity forces (g-forces) in high-speed maneuvers. Aided by the U.S. Navy and organizations in Allied countries, the AAF Aeromedical Laboratory at Wright Field, Ohio, developed the first clothing designed successfully to counteract the negative effects of g-forces. Early in 1944, U.S. crewmen began to use the G-suits in Europe. G-suits were tactically valuable because they helped fighter pilots maintain consciousness under high gravitational forces. One P-51 pilot, who was credited with shooting down five enemy planes on one sortie, wrote:

I found myself all alone in the middle of a bunch of Jerrys. Having no one to keep Jerry off my tail I had to keep full throttle and keep my air speed sufficient so that I could break away from anyone coming up on my tail. This maneuver would normally black me out but my G-suit kept me fully conscious of what was going on. I followed Jerry down to the deck, picking up an air speed of 600 mph. The Jerry went straight in without pulling out, and I would have, too, if I had not been wearing my G-suit.

Because of the special needs of such pilots and crewmen, the AAF during World War II often required and obtained its own support services, separate from those of the ground forces of the U.S. Army. Early in the war, the commander of the AAF, Gen. Henry

. Hap Arnold, decided to try to obtain his own system of AAF medical support. By wars end, AAF Air Surgeon Maj. Gen. David N. W. Grant had forged a medical service that was largely autonomous, although still subject to the authority of the Army Medical Department.

Two other notable AAF medical leaders were Malcolm Grow and Harry Armstrong, who directed the AAF medical program that helped air-crews cope with many new challenges in Europe. Grant, Grow, and Arm-strong were the best of a highly educated group of AAF medical professionals, many of whom volunteered to leave private practice to cope with new aeromedical challenges in distant theaters of war. On the home front, the AAF also administered a large network of hospitals and convalescent centers, and its programs in medical research, development, and training prevented many deaths, wounds, and illnesses in combat theaters. By the end of the war, the AAF had laid a foundation for the independent Air Force Medical Service created in July 1949.

AAF Medical Independence

Throughout the war, Air Surgeon Grant disagreed with the Army Surgeon General over the amount of independence the AAF medical system needed to fulfill its mission. Grant agreed with AAF leaders that the special matriel features of air warfare required a separate air force supply and logistics system, and he urged his military superiors to recognize the special needs of aerial combat and to give the AAF medical service the same degree of independence from the Army that most other portions of the AAF already had been given.

General Grant had developed his ideas on medical independence before World War II. In 1938, he graduated from the Air Corps Tactical School, the home of air power theory, which held that air power was a separate arm deserving a separate commander and support structure. The Tactical School produced many leaders who promoted an independent Air Force during World War II. Grant was the first and only medical corps officer to graduate from the school before Pearl Harbor. He was influenced by air power theory and by his readings on Dr. Theodore C. Lyster, the air surgeon in World War I who achieved a small measure of independence. After graduation from the Tactical School, Grant was assigned to England as an AAF medical observeran assignment that allowed him to study the aeromedical problems of the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Battle of Britain. In October 1941, Grant became Chief Air Surgeon of the Army Air Corps.

At the start of World War II, military airplanes were flying much faster and higher than ever before, creating new medical problems for aircrews. This technological revolution in aviation was yet another argument for a medical service specialized in aeromedical support. In fact, the AAF achieved some medical independence in March 1942 when a reorganization made the AAF equal with the Army Ground Forces (AGF) and Services of Supply (SOS). General Arnold, the AAF commander, was granted authority over some medical facilities, their patients, and the medical staff who cared for them. Air bases soon received surgeons and a medical reporting system was established. But official control of major logistical functions, including medical support, was delegated to the SOS, which evolved into the Army Service Forces command. The Army Surgeon General, who was subordinate to the SOS command, continued to claim ultimate jurisdiction over AAF medical services, a claim that crossed organizational boundaries. This boundary crossing caused problems. First, it prevented the highly mobile AAF, which sometimes created bases far from Army bases, from setting its own sanitary standards and procedures to prevent infection. Second, in combat theaters the AAF lacked its own station and general hospitals. Without them, it had to transfer many patients to Army theater hospitals where those patients often became administratively lost to the AAF. Because patients* medical reports were routed through long administrative channels, the AAF theater commander found it difficult or impossible to get reliable information on the health of the command.