Contents

Page List

Guide

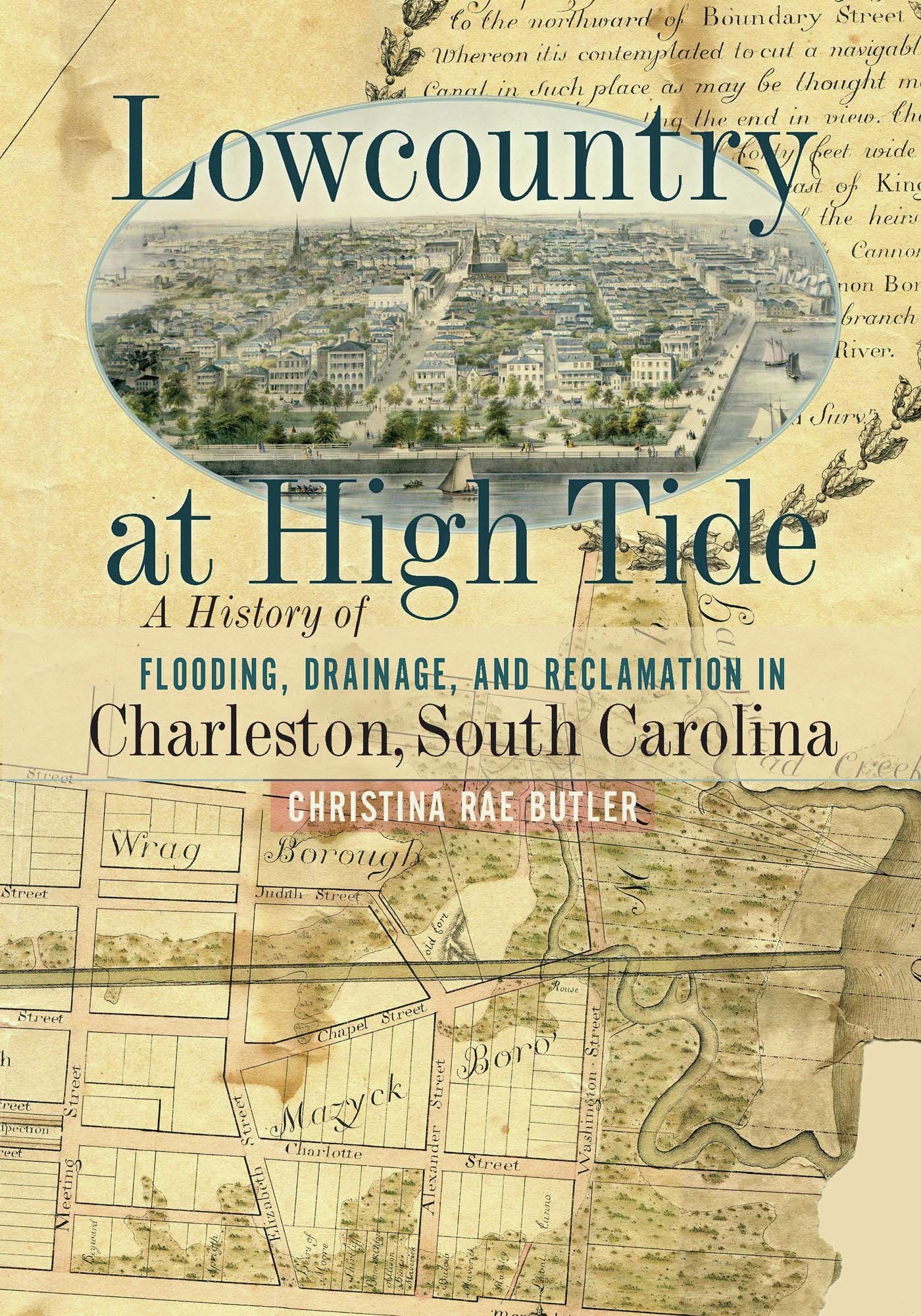

Lowcountry at High Tide

Lowcountry at High Tide

A History of

FLOODING, DRAINAGE, AND RECLAMATION IN

Charleston, South Carolina

CHRISTINA RAE BUTLER

2020 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.uscpress.com

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-64336-062-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-64336-063-8 (ebook)

Front cover illustrations: Plan of a part of Charleston Neck , 1807, courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society; INSET: Birds Eye View of Charleston, S.C., 1851, courtesy of Historic Charleston Foundation Archives

For Nic

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe a debt of gratitude to my colleagues, friends, and family for their help and support on my long journey toward completing this book. W. Scott Poole at the College of Charleston served as a resource and adviser early on and has since become a supportive friend. Professor Kerry Taylor of the Citadel Military College and George Hopkins, professor emeritus at the College of Charleston, also read portions of my text and provided constructive feedback. Alex Moore gave guidance and editorial advice when I decided to expand my efforts into a book. Beth Phillips invited me to present illustrated lectures about my research to her history classes at College of Charleston, which helped me identify contextual elements to include.

The librarians and archivists of the South Carolina Room and Charleston Archive at Charleston County Public Library (especially Amanda Holling, Molly French, and Katie Gray), the South Carolina Historical Society (especially Virginia Ellison, Molly Siliman, and Celeste Wiley), Mary Jo Fairchild with the College of Charleston Special Collections, Karen Emmons with the Historic Charleston Foundation, Anna Smith with the Charleston Library Society, and Steve Tuttle of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History assisted immeasurably with my research and image requests over the years. Meg Moughan and Rebecca Schultz with Charleston City Records Management provided access and insight to historic city engineering records. Bob McIntyre of the Charleston County Register of Deeds provided beautiful scans from the McCrady plat collection for inclusion in the book. Former city engineer Laura Cabiness kindly provided an interview about current and future drainage projects taking place in the city.

Richard Brown, director of the University of South Carolina Press, believed in this project and helped see it through to completion in innumerable ways. He offered editorial advice, suggested source material, and gave moral support. Economist Bruce Fitzgerald read the manuscript and offered helpful advice in interpreting early tax structures. Wade Razzi was congratulatory, kind, and understanding when book deadlines diverted my attention away from extracurricular duties at the American College of the Building Arts. Charles Lesser, retired archivist for the South Carolina Department of Archives, offered insight into archival materials and abundant helpful advice over the years. Many other friends reassured me along the way that the project would be useful to them as historians, tour guides, or as residents seeking to learn about the citys past, which encouraged me to complete the research and make it available as a publication.

I also wish to thank my parents, Dave and Rita Oberstar, for their unceasing encouragement and for fostering my love of history and the built environment from an early age. I have wonderful memories of visiting historic sites, watching This Old House, and reading anything related to history and buildings with them. As an adult I learned that my fathers favorite childhood book was Lets Look under the City (1954), a pictorial exploration of subterranean infrastructureit must run in the genes.

Most of all I am grateful to my husband, Nicholas Michael Butler, who has been an unceasing supporter and is a constant inspiration. His extensive knowledge of local source material and South Carolina history, and his editorial advice for the colonial chapter, was invaluable. Nic has been a patient and enthusiastic colleague, friend, and partner from the beginning stages of the project to its completion, and the book would not have been possible without him.

EDITORIAL NOTES

Lowcountry at High Tide utilizes primary sources in both typed and manuscript form, spanning more than three hundred years. The author has attempted to maintain a standard format for dates, monetary values, irregularities and misspellings, and name appearances in the written records. Individuals in the historic documents (especially civic) were often referred to by first and middle initials and last name. Every attempt has been made to identify individuals by their full first name. In the instances where given names could not be found, persons are referred to as they appear in the original document.

Some colonial and early federal-era newspapers have a single date, while others have a date range (South Carolina American General Gazette, 1017 April 1769, for example). Dates are cited as they appear in the historical document. In general, quotes and transcriptions in this book duplicate the historic syntax, spelling, and emphasis used in the original document. Editorial modifications in [square brackets] are used where words either are missing or are so problematically spelled as to obscure meaning. Monetary amounts are cited in the currency and value in which they appear in the primary source documents. I have not converted them into 2020 currency because the data will quickly become irrelevant with the forward passage of time. One is able to compare figures of the era at hand to note spending preferences in relation to other projects and areas of the city at a given time period without conversion.

Introduction

Since settlers first established the city of Charleston, South Carolina, on a peninsula situated at the confluence of the Cooper and Ashley Rivers, inhabitants have manipulated its physical outline and topography in an attempt to transform the settlement from a marshy, flood-prone finger of land with numerous inlets and creeks into a well-drained and more uniformly shaped landmass. In the past 340 years, residents have greatly increased the usable landmass of the peninsula, a challenging endeavor in the face of environmental, economic, and social obstacles. This book documents the peninsulas expansion, analyzes how the challenges to physical growth were overcome, and examines the implications of past filling activities for Charlestons future. It addresses the history of drainage and landfill and the entwined political, social, and public health issues stemming from topographic challenges and change. A thorough history of fill and reclamation is overdue in a city in which flooding has been a continuous hindrance to human habitation since European settlers first recorded the phenomenon in the late seventeenth century.