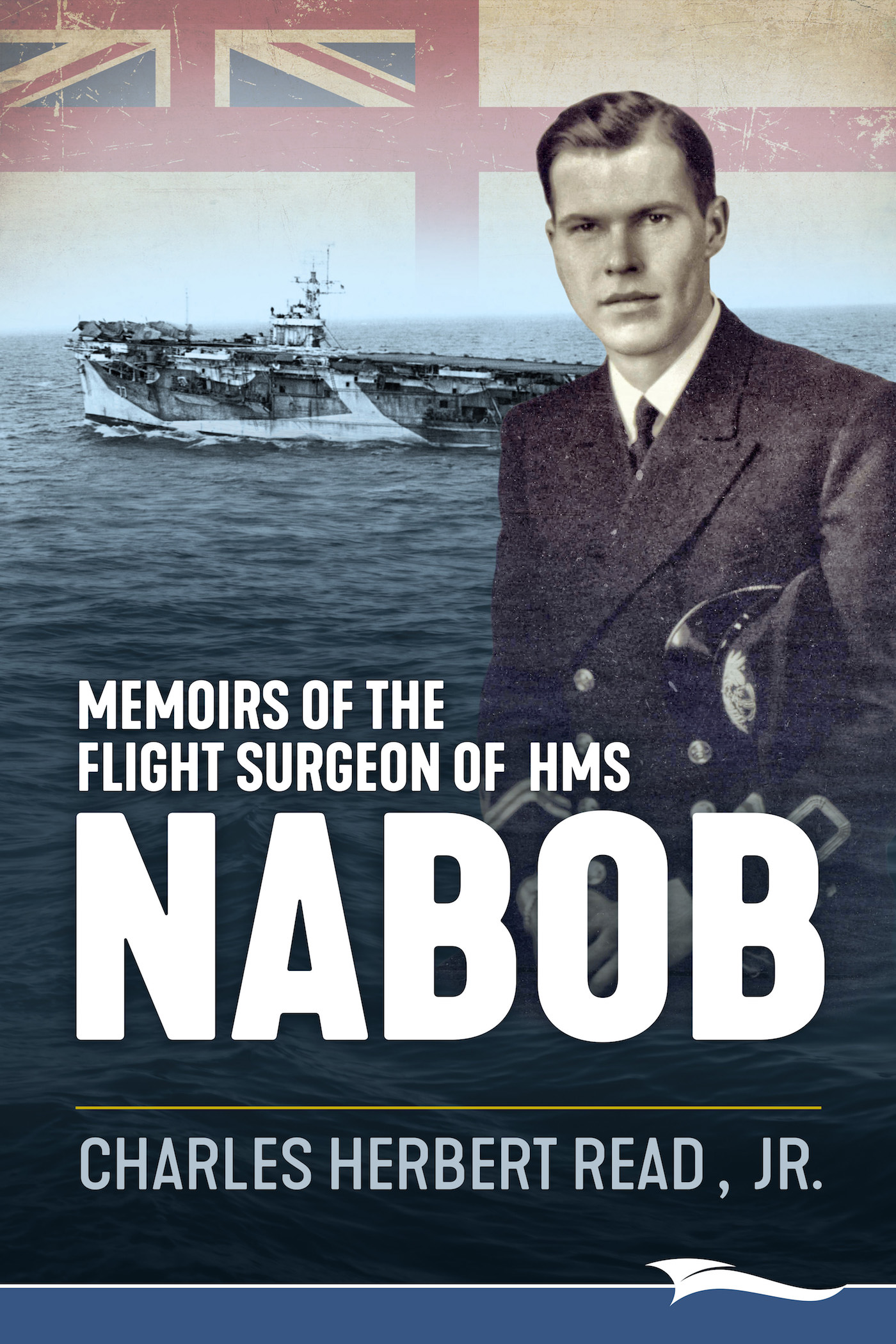

Memoirs of the Flight Surgeon of HMS Nabob

by

Charles Herbert Read Jr.

MDCM

Surgeon Lieutenant RCNVR (R)

Published by Lammi Publishing, Inc., headquartered in Coaldale, Alberta, Canada.

http://lammipublishing.ca

Copyright by Charles Herbert Read Jr. in 2018. All rights reserved.

This book is a memoir. The conversations in it were not recorded, but were reconstructed from the authors memory.

Text editing by Karen Hann

Cover design by Paul Hewitt, Battlefield Design

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Read, Charles H., Jr., 1918-2016, author

Memoirs of the flight surgeon of HMS Nabob / by Charles Herbert Read Jr.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-9950060-8-9 (softcover)

ISBN 978-0-9950060-7-2 (Amazon Kindle)

ISBN 978-0-9950060-6-5 (EPUB)

1. Read, Charles H., Jr., 1918-2016. 2. Nabob (Aircraft carrier). 3. Great Britain. Royal NavySurgeonsBiography. 4. World War, 1939-1945Personal narratives, Canadian. 5. World War, 1939-1945Naval operations, Canadian. 6. CanadaHistory, Naval20th century. 7. Great BritainHistory, Naval 20th century. I. Title.

D772.N3R43 2017 359.3' 2550941 C2017-903321-2

C2017-903322-0

To all the men and women who fought Hitler and his Nazis, especially to those brave men who served on the HMS Nabob.

Table of Contents

An Odd Name for an Aircraft Carrier

The rocky peninsula of Halifax is partially surrounded by one of the most coveted features of a northern coastal settlementan ice-free harbour. The Halifax Harbour has been vital to Canadas defense and development throughout our birth and early growth as a nation.

The British Empire created a military outpost in this harbour in 1749. The Royal British Navy established the first dockyard there, and the facility has grown and expanded ever since, passing into Canadian control in the early 1900s. It underwent massive expansion during the First World War, only to be severely damaged in the infamous Halifax explosion of 1917 and then quickly rebuilt. These dockyards are also the site of the legendary Pier 21, where over a million immigrants entered Canada, weaving in their own colours and patterns into the fabric of this nation. Today, it remains a commercial port, a tourist site, and a military stronghold.

At the North End of the Halifax Peninsula, the British Army built the Wellington Barracks in 1797. The site of these barracks eventually moved into Canadian hands, and at the onset of the Second World War it was appropriated by the Canadian Navy and transformed into the facility known as HMCS Stadacona. Such historical Canadian landmarks as Wellington Gate and Admiralty House remain standing there to this day.

It was there that I, as a new medical officer in the Royal Canadian Navy, reported on 3 January, 1944. The Officer of the Day at once told me I was to report to Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Neil Chapman in the outpatient clinic in the dockyards. After a relatively short walk, I found him standing in the door of his office, holding a piece of paper. I thought he looked like someone who had just been surprised. Then he saw me. After welcoming me, he told me that he had received a cable from headquarters in Ottawa, telling him the wonderful news that the Canadian Navy had just acquired an aircraft carrier. He showed me the document.

Chapman was obviously excited. Now that our navy had an aircraft carrier, we really had it all. During the First World War, Canada had been a British dominion, subject to the decisions of the British Parliament. Wed proved our mettle as a nation then, fighting such legendary battles as the Somme, Vimy, and Passchendaele. Now, thanks to the Statute of Westminster, we were a fully sovereign nation, able to make our military decisions independently. Of course, as responsible citizens of the world who were horrified at the atrocities of Hitler, we had joined the Allied war effort. In the First World War, aircraft carrier technology had been rudimentary, but the inter-war years had brought about innovations allowing for far more effective, large-scale use of the vessels. Aircraft carriers allow naval forces to project air power great distances without having to depend on local staging bases, a true union of air and sea warfare.

This news was also tremendously exciting to me. Up until now, being a physician in the Canadian Navy had meant to me that in due course, I would probably get to go to sea on a corvette, frigate, or maybe even a destroyer, and I would see new places and have many new experiences. Furthermore, Id be involved in any action and share the same risks as the rest of the crew. But now, this joining of the air and the sea at once seemed to me to be a whole new and ideal way to fight the anti-submarine war. Immediately, I decided I wanted to be the flight surgeon on that aircraft carrier, because it would epitomize the way I could best contribute to the war effort and Hitlers defeat. In that role, I thought Id be attending to the special needs of the aircrew as well as the general medical needs of the others of the crew.

But over the next few hours, when I thought about my chances of getting that appointment, it struck me that they were virtually zero. I spent time at the legendary Admiralty House, where I learned more. Admiralty House had once been the official residence of the admiral of the North American Station of the British Royal Navy, housing such famous residents as Admiral Thomas Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald, and Admiral Francis Austen, brother of Jane Austen. After it passed into Canadian hands, it served as a naval hospital in the First World War (sustaining heavy damage in the Halifax explosion), and now, in the Second World War, as an officers club. I had no seniority, and from listening to the lunchtime chatter, it was evident that virtually all the fifty or so other medical officers at Admiralty House (then the Naval Officers Club in Halifax) all wanted it. And that was not considering the three hundred and more doctors elsewhere in the navy, all of whom had more seniority than I, and all of whom probably wanted that position as much as I did.

I needed to find a way to set myself apart and increase my chances.

The only thing I could do was to make it known that I wanted that appointment; the worse that could happen then would be that I would be ignored or told no. That very afternoon, I found out that the most senior medical officer at Stadacona was Surgeon Captain David Johnston, and therefore, I naively presumed, the person who would make the decision.

I made an appointment to see him as soon as I could. It turned out to be the next afternoon.

So when I knocked on his door, I made sure I was precisely on time. A pleasant voice invited me in. He was alone. As he rose to greet me, I saw he was of medium height, and other than having four wavy gold rings separated by scarlet ones on both sleeves, he looked much like the kindly, middle-aged physician hed probably been before volunteering for the service. The warmth of his personality and the tone of his voice put me more at ease, but I was careful to stand at attention with my cap properly tucked under my left arm. He invited me to have a seat and did so himself, asking how he could help me.

My statement was brief. I told him that I was aware wed just acquired the aircraft carrier, and I would dearly love to be a medical officer aboard the ship. I hoped that when the time came to assign someone, he might consider me.