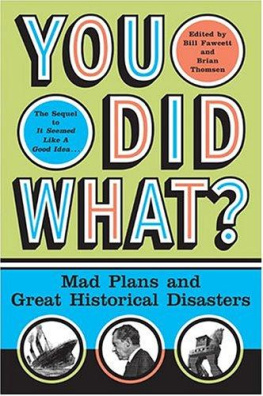

WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN and BILL FAWCETT

So many bad decisions, so few pages. When one studies history and has the advantage of 20/20 hindsight you are constantly amazed at the decisions made by otherwise very intelligent leaders. Stalin helped train the German Panzer Corps, Napoleon turned away Robert Fulton and his paddlewheelers, and the Kaiser's own spies actually smuggled Lenin into Russia to start his Bolshevik revolution. There are so many examples of seemingly irrational decisions that one sometimes has to wonder about the sanity of the decision maker and the many other equally possible courses history might have taken.

To be included in this volume the decisions had to meet a few qualifications. First they had to be seriously and unquestionably bad. Further, the decision had to be of some importance, affecting thousands, if not millions, of people. Generally we avoided using decisions made in the heat of battle. Too many can be explained by poor generalship or limited intelligence. Finally the decision, given the information at hand and the way things were done at the time, had to seem like a good idea, even the best of all possible options, but for some small fault in logic or unconsidered possible circumstance that would prove in the end catastrophic.

So enjoy a look at history's follies and feel superior to some of the past's greatest leaders. But occasionally stop and ask yourself which of the decisions being made today, the ones that seem our leaders' most rational, will be included in the 2099 edition of this book.

Bill Fawcett

IT

SEEMED

LIKE A

GOOD

IDEA

The Death of Philip of Macedon

4th Century B.C. Macedonia

by William R. Forstchen

Throughout most of his reign Philip of Macedon suffered from bad press and a serious inferiority complex. Though he had built his kingdom into the preeminent power of the Greek world, his far more cultured neighbors to the south, Corinth, Athens, and Sparta, still viewed him and his followers as crude mountain-dwelling barbarians. His own personal history and appearance didn't aid his acceptance by the upper crust. He was first and foremost a military leader who took armies into battle personally. As a result he had suffered a score of wounds. The two most grievous blows had been the loss of an eye and a spear thrust into his thigh. Neither wound had healed properly and both continued to ooze. The leg in particular emitted a horrible smell. It was also rumored that he had committed the heinous crime of matricide in clawing his way to the throne.

His personal life was equally scandalous. His first wife was a priestess of Dionysius, in modern terminology, a temple prostitute. At that time the practice was far more accepted and she did claim the distinction of being the daughter of a minor king. The real scandal was their very public falling out. She had borne Philip a son, the legendary Alexander, and then proclaimed openly that Philip was not the father; rather it was the god Zeus, who had visited her bedchamber in the incarnation of a snake. Modern political and sexual scandals pale in comparison to the dynamics played out in the royal household in the capital city of Pella. Philip was proclaimed a cuckold by his wifeshe was known to hang around with snakesand the king became notorious for his desire to sleep with anyone who was willing, male or female.

His interactions with Alexander could be described as a love-hate relationship. On one hand, there seemed to be moments of genuine affection between the two. Philip did everything possible to groom him for command, retaining the most famous scholar of the age, Aristotle, to serve as the boy's tutor, and he craved Alexander's acceptance by the high-browed Greeks. For his part, young Alexander, in his first major battle, threw his own life on the line in order to save his father who had been surrounded and was on the point of being overcome. Alexander literally placed his own body between his father and the enemy spears.

And on the other hand hatred flared as well, especially as the boy entered early manhood. The bitterness between the boy's mother and the king simmered for years, and boiled over when Philip took a new wife, a girl the same age as Alexander. At the wedding feast one of Philip's drinking buddies toasted the new marriage and the chance to produce a legitimate heir to the throne. As a result father and son came to blows, and on the same night Alexander and his mother fled the city, a wise move since the king might very well have had both slain in his drunken rage. For over a year civil war ensued between father and his wife and son. A truce was finally declared and the two were allowed to return.

Meanwhile, Philip's dream of bringing all of Greece to heel was at last coming to pass. At the legendary battle of Chaeronea, fought in 338 B.C. , Philip defeated a combined Athenian-Theban army nearly twice his size; and the following year, at Corinth, the Corinthian League was proclaimed, an alliance of all of Greece under the aegis of Philip. Though not accepted as a social equal, the strength of his army had created him supreme warlord of all the Greeks, ready to embark on a campaign into Asia against the Persian Empire.

Alexander was the only fly in the ointment. Sent by the Macedonian king to serve as ambassador, the young Alexander had become an instant celebrity, touring Greece like a triumphal hero. The contrast between father and son was remarkable. Here was not a grizzled warrior, smelling of decaying wounds, aged from drink and sexual excess; many proclaimed that the young Alexander seemed like an earthly manifestation of a god, brilliant, witty, good-natured, physically strong and agile, stunningly handsome, the true Greek ideal of perfection. Word of Alexander's successful tour came back to Philip and caused even more unrest. The old king had led the armies and won the battles, yet it was the young upstart who seemed to be taking all the glory. Furthermore, the dark, unsettling rumors, first spread by his first wife, Olympias, were now being voiced openly: that Alexander had in his veins not the blood of Philip but rather the blood of a god.

In preparation for the campaign into Persia, a religious festival and games were to be held in Pella. As king, Philip was also chief priest, and it was his responsibility to march in procession to the temple and then to the arena to start the festivities. Representatives of all the Greek city-states would be present, many of them traveling to Pella for the first time. The city went all out in preparation, for Pella was no longer a rude barbarian capital, but must now prove itself the new heart of Greek civilization and culture.

Adding additional tension to the festival were Philip's new wife and his newborn son. Philip's old drinking buddies and the family of his new wife started to openly whisper that here at last was a true heir untainted by rumors of illegitimacy. There was another undercurrent persisting as well. An old male lover of Philip, a member of his personal guard, had had a falling out with a rival for Philip's attention. This rival had recently been killed in a skirmish and his dying wish was that his competitor should somehow be humiliated. The dead rival's wishes were carried out: Philip's old lover was invited to a party, bound, then tossed out into the street to be abused by servants and slaves. When he went to Philip to complain and demand justice, Philip took the entire incident as an uproarious joke and laughed the young man out of court for being unable to defend himself. These various currents, plots and counterplots now came to a head.