Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

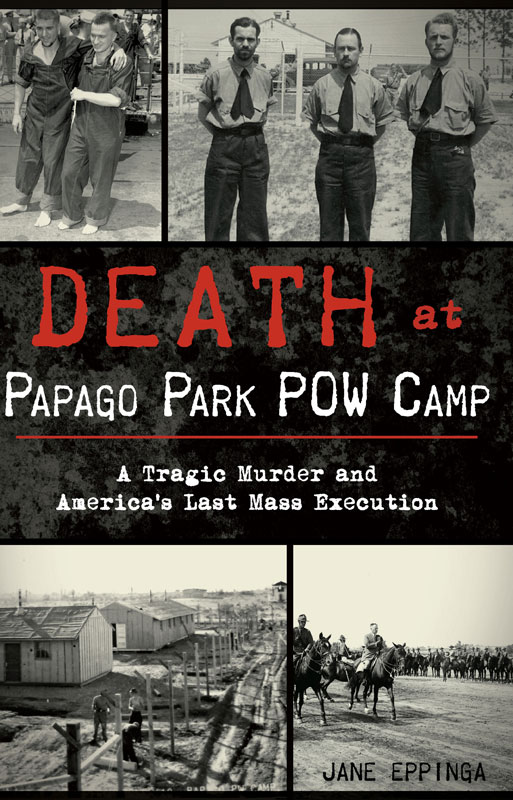

Copyright 2017 by Jane Eppinga

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.43966.086.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931815

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.576.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work of a book is never entirely the work of one person, and so it is with Death at Papago Park POW Camp: A Tragic Murder and Americas Last Mass Execution. Now is the time to round up the individuals and organizations that have generously helped me. These include the Arizona Historical Society Library, the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the Judge Advocate Office, the Harry S Truman Library, the Wisconsin Historical Society, the Monroe County (Wisconsin) History Room and the Santa Barbara Historical Society in California. Individuals include the late Bernard Fontana, the late Rhea Robinson and the late Dorothy and Lawrence Jorgensen. Special thanks to Frederic L. Borch III, regimental historian and archivist, the Judge Advocate Generals School, U.S. Army, and to Retired Captain Jerry Mason, who shared his magnificent U-boat archive with me. Special thanks to my panel of experts, the Wednesday Lunch Bunch. No book sees the light of day without a publisher and an editor, including Artie Crisp, Hilary Parrish, Anna Burrous and the rest of The History Press staff.

INTRODUCTION

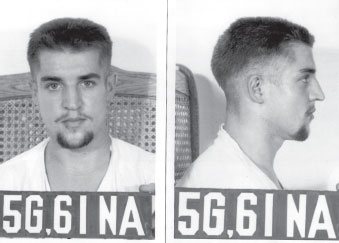

Werner Max Herschel Drechsler received an honorable military burial at Fort Bliss, Texas, on June 17, 1946, a little more than two years after his brutal execution by his German compatriots on March 12, 1944. Drechslers murder underscores a unique moral dilemma. Was his hanging for treason by his countrymen murder or treason, and did his execution constitute an act of war? Or was it murder? Or was there even a difference? No physical evidence of Camp Papago Park remains today in what is now a residential section in Scottsdale, Arizona, near the Cross-cut Canal. However, during World War II, about 375 Americans guarded more than 4,000 German prisoners at Camp Papago Park and its outlying camps. Once the Germans and Americans were enemies, but after World War II, the dwindling numbers of Americans and Germans held meetings in a spirit of friendship, through a group known as the Camp Papago Trackers, whose creed was To renew in friendship the association which commenced in anguish.

Former prisoners love to laugh and talk about the great escape attempt through the faustball tunnel. They do not care to speak of Camp Papago Parks dark side. Violence by Nazis against anti-Nazi Germans resulted in brutal beatings and death. They deny any knowledge of the Drechsler murder even though they were incarcerated at Camp Papago Park at the time of his execution. However, Americans such as Dorothy and Lawrence Jorgensen served at Camp Papago Park, and they remember well the morning that the Americans discovered Drechslers corpse hanging from a bathroom rafter. Dorothy took care of the prisoners records when they arrived and helped them fill out their information cards. Her husband, Lawrence, was a POW guard and became the twenty-sixth man to enter the faustball tunnel after its discovery.

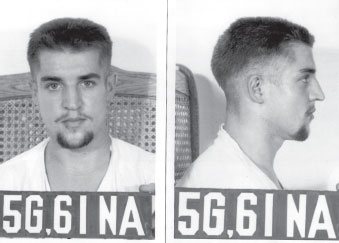

Werner Drechsler, German prisoner of war. Courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C.

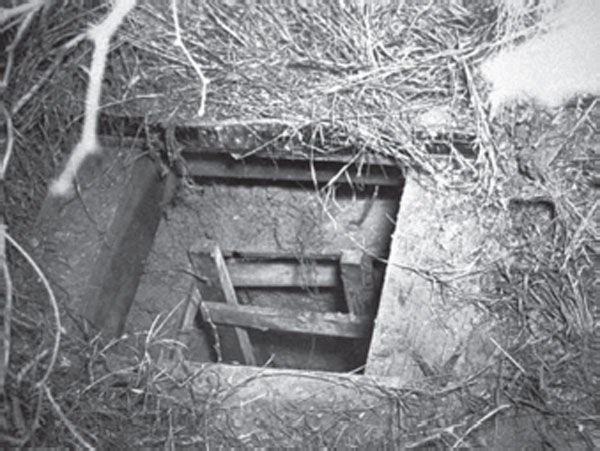

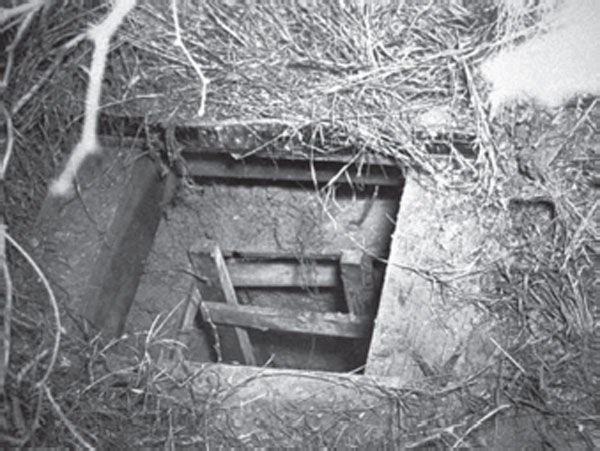

The German prisoners asked for permission to create a volleyball or faustball court, and the guards provided them with digging tools. Two officers involved with the Werner Drechsler case, Jurgen Wattenberg and Friedrich Guggenberger, were also involved with the great escape through the 178-foot tunnel, which exited near the Cross-cut Canal. Wattenberg ordered the men in the adjacent compound to throw a noisy party the evening of December 23, 1944. At 9:00 p.m., prisoners started crawling out along the tunnel. Next door, their German buddies were singing and breaking bottles. Each escapee carried clothing, food, forged papers, cigarettes and medical supplies. They planned to float down the Cross Cut-canal to the Salt River to the Gila River and on to the Colorado River, which would take them into Mexico. They constructed a raft that could be taken apart. To their disappointment, the Gila River was totally dry.

On December 24, the twenty-five officers and enlisted men had escaped. The escape was discovered when Herbert Fuchs surrendered at the sheriff s office, wet and cold. Several days later, Private Lawrence Jorgensen discovered the camouflaged escape hatch. By the end of the month, Wattenberg had stopped at several Phoenix hotels and asked about a room for the night. He fell asleep in an empty chair in the Hotel Adams lobby. When he left, he was arrested by the police. Near the Mexico border, Guggenberger was arrested and returned to the camp. Jorgensen, who became known as the twenty-sixth man, entered the tunnel and followed it to the end. After a little more than a month, all of the escapees were recaptured.

The faustball tunnel through which twenty-five German POWs escaped from Camp Papago Park. Courtesy Dorothy and Lawrence Jorgensen.

Lawrence Jorgensen served as a guard, and his wife, Dorothy, worked as a secretary at Camp Papago Park. Courtesy Dorothy and Lawrence Jorgensen.

The states participation in the war effort continued with the raising of the flag by the Pima Indian Ira Hayes at Mount Suribachi; the internment of Japanese Americans in relocation camps; the incarceration of the Japanese consular staff from Hawaii, who gave the orders on where and when to drop the bombs on Pearl Harbor, at a southern Arizona ranch; the large prisoner of war camp established for Italians at Florence in central Arizona; and the numerous German prisoner of war camps throughout the state.

The United States faced the problem of how to treat the flood of enemy prisoners that landed on its shores. After World War I, representatives from forty-seven countries met in Geneva, Switzerland, to discuss the problems of caring for prisoners of war. Signatory nations promised to treat prisoners humanely. Prisoners had a right to clean, safe accommodations and to rations equal in quality and quantity to whatever was served to the detaining powers troops. They were to have access to recreation and to be allowed to buy personal items at military canteens. Representatives from the Red Cross and neutral nations inspected the prison camps.

Prisoners could be kept comfortable in states such as Arizona with a minimum cost of heating fuel. Arizona became a training ground for American soldiers destined to fight in North Africa. Two waves of prisoners of war arrived during World War II. The first group came in 1943 after North Africas surrender, and the second contingent arrived during the first weeks of the 1944 Normandy landings. At Norfolk, prisoners had medical checks before being sent to various camps.

Next page