Love and scandal are the best sweeteners of tea.

H enry F ielding

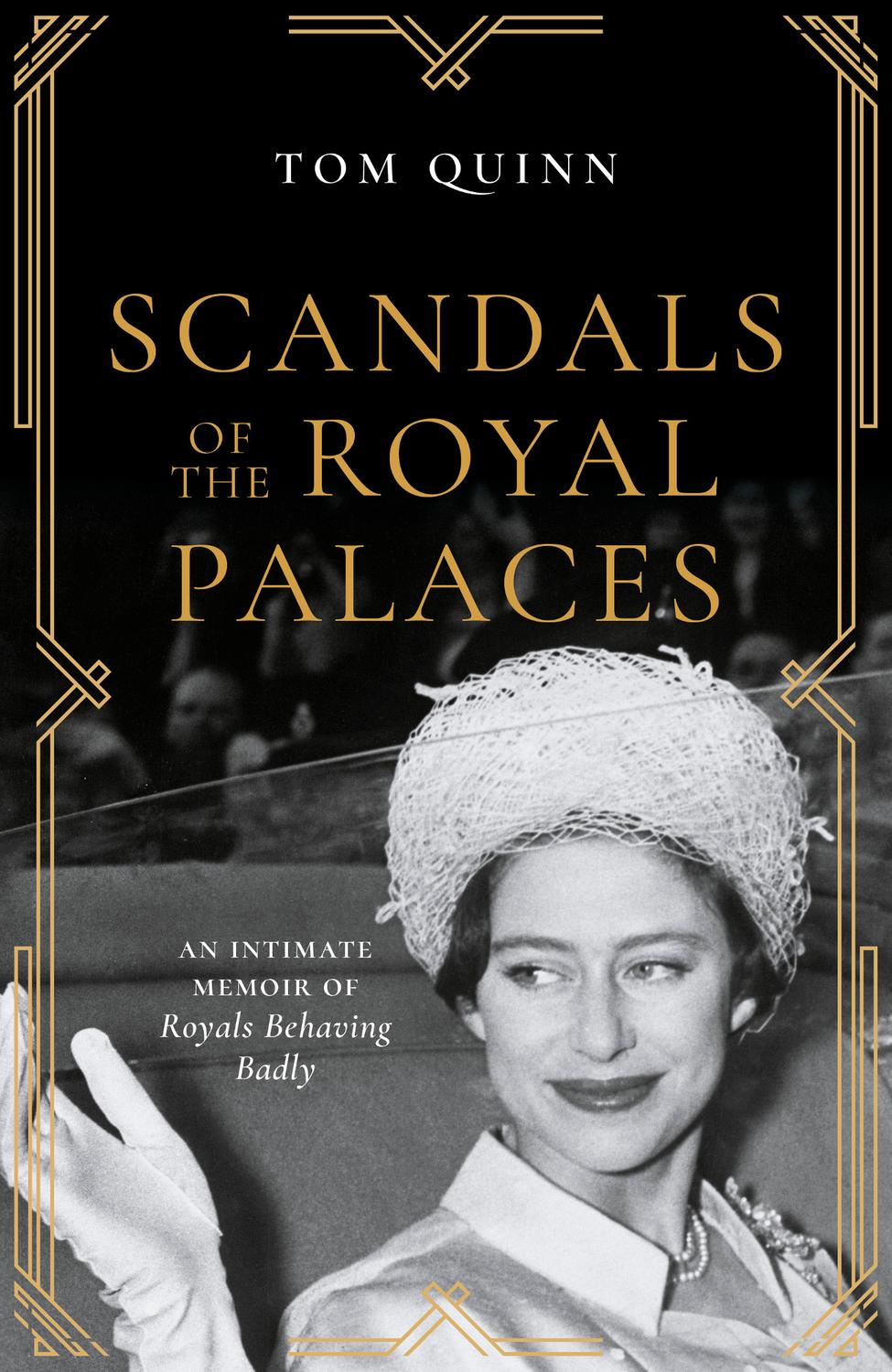

G eorge Orwell once said that the British love a really good murder, whether in their novels or their Sunday papers. He might also have said that the only thing the British love more than a good murder is a really good scandal, and best of all are the political and sexual scandals that emanate from Britains royal palaces.

Of course, the kiss and tell story is now a commonplace, but scandal itself isnt a recent phenomenon. It has a long history; one tied up with power and position, especially royal power and royal position; a history that includes scandals in such high places so damaging Edward and Mrs Simpsons relationship, for example that when they do blow up, they become lodged in the collective consciousness never to be forgotten.

But dozens of other royal scandals have been covered up or viii suppressed to some degree by an establishment that is famous for its determination to keep royal secrets, well, secret.

This book is the first in-depth look at the outrageous behaviour of not just the royals themselves but also palace officials, courtiers, household servants and hangers-on. Covering existing royal palaces in some depth as well as taking a briefer look at scandals linked to long-vanished royal residences such as Whitehall, Nonsuch and Kings Langley, Scandals of the Royal Palaces also includes new information on well-known and not-so-well-known scandals, including those that have only recently been revealed in detail through the release of previously secret official papers.

Political, social, financial and sexual scandals have been linked to Britains royal palaces for centuries from Edward II potentially being killed because of his attraction to men to drug-fuelled and lesbian queens, perjurers, liars, thieves and even Nazi sympathisers, the royal residences have seen it all.

The behaviour of todays royals seems perpetually to threaten scandal; three of HRH Queen Elizabeths children are divorced following adulterous affairs and one was the friend of a notorious paedophile. Meanwhile, the two sons of the Prince of Wales himself no stranger to scandal have publicly fallen out with the press and with each other.

As this book will show, scandal and the royal family have always been strange and not-so-strange bedfellows, and key to the sometimes extraordinary scandals the royals have become involved in are the palaces in which they live. Free to move between some of the most luxurious homes in England Windsor ix Castle, Kensington Palace, Balmoral and Buckingham Palace, to name but four and living in a world of excessive deference and financial security, members of the royal family find it impossible to resist the lure of flattery and personal power. Since they are often unhappy in their gilded cages it is perhaps no wonder that down the ages royal men and women have used their position and influence to get what they want whether that be sex, drugs or money while hoping to maintain their reputations as moral leaders.

Readers may ask, why a book about royal scandals, many of which are already well known? First, new information is always becoming available. Second, interpretations and our understanding of the past change as society changes. We are far more accepting of same-sex relationships today, for example, than we ever were in the past. We are also far less deferential to the royal family. Even fifty years ago biographers of members of the royal family tended to gloss over their subjects sexual peccadilloes.

Few today would think it a good thing always to suppress the misdeeds of royal individuals just because they happen to be royal. The sense that we are all equal is far stronger now than it was historically when the sole aim of the establishment was to protect the reputation of public figures by whatever means necessary. Where biographers and historians in the past felt their role was to uphold the dignity of members of the royal family by suppressing anything deemed to be damaging to their reputations, we now see that a warts-and-all picture is far more accurate and interesting.

The truth is that we have come a long way so far, indeed, x that in 2018 the royal family happily announced the marriage between Ivar Mountbatten, a cousin of the Queen, and his partner James Coyle. Perhaps what makes this even more extraordinary and further evidence of just how far we have come in our attitudes and values is that Ivars former wife, Penny Mountbatten, gave her ex-husband away.

The world is a healthier place since the death of Earl Mountbatten of Burma, Ivars ancestor, who spent his life concealing from the public and his friends his promiscuous taste for young men; a taste he was happy to indulge to an extraordinary degree safe in the knowledge that no newspaper would ever print anything he did not like.

We live in an age of far greater freedom; freedom to discuss the lives, loves and indiscretions of the most famous family in the world, a family whose members as we will see have intrigued and embarrassed, outraged and entranced us for centuries.

Is it not strange that he is thus bewitched?

C hristopher M arlowe, E dward II

V isitors to London are sometimes confused by the fact that the British Parliament meets in the Palace of Westminster, a building that is obviously not a palace at all. In fact, the name has survived where the palace, in the sense of a royal residence, has not. We know that the late Saxon kings including Cnut and Edward the Confessor lived in a palace where the palace of Westminster now stands. The area was once known as Thorney Island, a marshy area, criss-crossed by streams and surrounded by mudflats but which lay at an important and strategic crossing point on the River Thames. Edward the Confessor built the first palace there. He also built, probably simultaneously, the great minster or church Westminster Abbey which still stands, though much altered, today.

It is difficult today to visualise the very early palace because over succeeding centuries it gradually expanded until it sprawled from the river across almost to St Jamess Park in one direction and from the Jewel Tower, which still exists, to Charing Cross in the other. The palace eventually surrounded the abbey itself and continued past the Jewel Tower to what is now Great College Street. Beyond the outer wall, which followed the route of modern Great College Street, was a narrow path and a water-filled ditch, the remains of which were discovered during work in the 1970s.

The fact that the minster and the palace were almost coterminous in this early period simply reflects the closeness between the king and the church, between temporal and spiritual power. And it was to the old palace at Westminster that the Kings Council (the Curia Regis), the forerunner of Parliament, was summoned whenever the king felt it was necessary. Nothing remains of the buildings from the time of Edward the Confessor or indeed from the time of William I, but William IIs magnificent Westminster Hall still exists and it was there that the king met his council. Of course, during the medieval period, the king tended to move almost continually around the country and ministers and advisers would follow him, but the Palace of Westminster along with the Tower of London were his London residences.

By modern standards, the old medieval palace would have seemed sparsely furnished with simple wooden furniture and chests but also rich fabric hangings dyed in surprisingly bright colours. Visitors to the meticulously restored rooms at the Tower of London can get a more accurate idea of what the kings apartments at Westminster might have looked like. But we should remember that important items, such as the kings bed, were deliberately made in such a way that they could easily be dismantled to be carried with the king on his never-ending journeys around the country.