Introduction

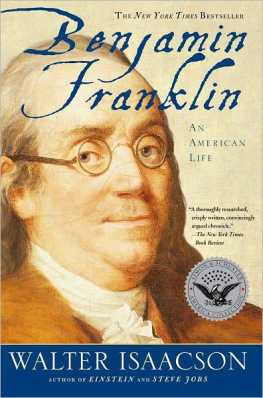

I t took more than a millennium before Europes centuries of learning and creativity produced the Renaissance, that golden era when human intellect shone a bright light that cast out the shadows of the Dark Ages. The pace was a little faster in the New World. Less than two hundred years after the first English settlers set foot on the continent of North America, the United States had produced a Renaissance man, a man of humble beginnings who boldly left his mark in politics, science, education, philosophy, diplomacy, and innovation. That he was able to be so versatile is both a tribute to his natural intelligence and character, but also a testament to the inventiveness of his homeland. Its true that all subsequent civilizations build upon what went before, but the legacy of Europe was so rigid that, in order to rise to a position of status, a man needed either his own august lineage or wealthy and influential patrons.

For Benjamin Franklin, there was no exalted institute of education that provided him with learning; there was no vast store of wealth to bankroll him. He was, in fact, deliberately and enthusiastically, a member of the middle class, a man who had pulled himself up by his own bootstraps and then figured out a way, metaphorically, to make a better bootstrap. He was thrifty, patriotic, shrewd, and virtuous; he had a common-law wife, an illegitimate son, and a reputation as a flirt among the ladies of France, who adored him when he was well past the age for such dalliances. He was a pragmatist, a writer, a statesman, a scientist, an inventor, a philanthropist, a citizen; Benjamin Franklin was so many things that it took eighty-four years for him to bring them all to fruition.

Benjamin Franklin, American, is a legend. He is also endearingly, unmistakably human. Meet the man who was his nations first celebrity and discover how Franklin, who has been called The First American, remains a fascinating man whose personality has not been dimmed by the passage of time. View him in his ordinary, eighteenth-century garb and posture, but dont be fooled: Benjamin Franklin is part of every American entrepreneur, innovator, and crusader who has ever lived because his virtues came not from his time, but from the timelessness of his talents and the boundless rejuvenation of his native soil.

Born in Boston

We are all born ignorant, but one must work hard to remain stupid.

Benjamin Franklin

T he small house on Milk Street, Boston, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was crowded with children. The birth of Benjamin, on January 6, 1706, made the twelfth of the Franklin offspring born to Josiah, who earned his living by making soap and candles, and Abiah, his second wife, who would contribute ten children to the brood which would eventually number seventeen.

Education for the Franklins was desirable, but money was tight, and Benjamins time in the South Grammar School when he was eight years old only lasted a few months because his father couldnt afford the cost. He returned to school, this time to George Brownells English School, for one year, and wanted to study longer, but formal education was a luxury that the family couldnt afford.

At the age of ten, it was time for young Benjamin to settle on a trade. His father let him watch the Boston tradesmen at their labors, but Benjamin wanted to be a sailor. However, Josiah Franklin had already seen one of his sons go to sea; he was unwilling to permit another do the same. The boy didnt want to follow in his fathers footsteps making soap and candles, so for a short time, he was indentured as a cutler. Ultimately this didnt interest him.

Even with minimal schooling, however, it was obvious that the boy had a lively intellect. He was only eleven years old when he started to read the English novelist Daniel Defoe, the Greek historian Plutarch, and the Puritan minister Cotton Mather. The Franklins were a Puritan family, and his parents hoped that their son would become a clergyman when it was time for him to settle on a career. In colonial Massachusetts, ministers were held in high regard; Franklin would later humorously write in his Autobiography that he was his fathers tithe to the church. That tithe would go unpaid, as Franklin in his youth had no interest in the ministry; as an adult, he had no vocation for it.

But despite his disinclination for the life of a clergyman, Franklin would absorb the characteristic traits of the Puritan and would exemplify them in his writing and lifestyle. Puritans held to a simple code of behavior: work hard, be honest and diligent, and live simply and frugally in order to obey and serve God. As an adult, Franklins motives may not have been directed toward God, but the Puritan creed had taken root in fertile soil.

He ended up apprenticed to his half-brother James, a printer, and at the age of twelve, he was signed up for nine years of indenture. Despite his lack of formal learning, Benjamin was a bookish boy who enjoyed reading and liked to write poetry. As an apprentice to a printer, he could further his writing talents, something he did by spending hours creating an outline of the essays he had read in the popular magazine the Spectator , and then rewriting them in his own style, teaching himself how to communicate in a manner that reached his readers. He also wrote a ballad to commemorate the capture of the pirate Blackbeard, who had terrorized the Eastern coast. He had a lively writing style that would mature as he plied his craft, even though his brother displayed no great interest in expanding Benjamins literary horizons.

In 1720, Franklin began to explore his own personal independence. He moved from the family home into a boarding home, and he stopped going to church so that he could use Sundays for more studying. His religious concepts changed; by the next year, he was a Deist. His personal life would change in other ways, too; Franklin, looking for ways to save money so that he could afford to buy books, decided to become a vegetarian.

In 1721, brother James started a newspaper, The New England Courant . What made this newspaper unique was that, unlike the other two Boston newspapers that reprinted articles that originated from Europe, James Franklin recorded news from home: ship schedules, articles, opinions, and advertisements. He was also open to publishing articles that educated and entertained.

A series of essays, submitted under the pseudonym of Silence Dogood, became popular with readers for their humorous tone and their mockery of Bostonian society. Silence Dogood was a widow who provided advice and criticism of her world, particularly on the subject of the treatment of women. James didnt know the identity of the author, but Benjamin submitted the articles anonymously because he knew that his brother would not welcome his work. So he wrote the articles at night and stealthily slipped them underneath the door of the print shop, maintaining the mystery of the authors identity. Sixteen letters from the opinionated Mrs. Dogood were printed before Benjamin confessed his authorship. James didnt handle his brothers talent or budding fame well and scolded him for his actions.

Benjamins talents and precocious ability to work as a printer stood his brother in good stead when James Franklin ended up in prison for three weeks, charged with contempt for the criticisms he printed of the Massachusetts government. Freedom of the press did not exist as a right in the colonies. When a controversy arose over whether or not inoculation against smallpox was a sound medical principle, the Franklins were on the side that opposed inoculation; the powerful and influential Puritan clergy family, the Mathers, supported it. Bostonians tended to agree with the Franklins and believed that inoculation made people sicker, but they looked up to their clergy and didnt approve of James Franklins disrespectful tone.