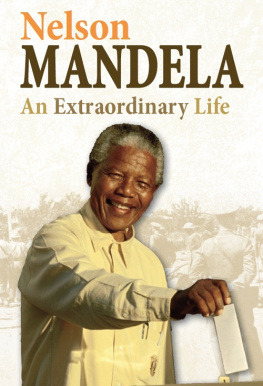

A boy in rural South Africa

T he area along the banks of the Mbashe River, near Umtata in the Eastern Cape, was a highly disputed area of South Africa for many years. However, his did nothing to destroy the charm of the gentle, undulating softness of the rolling hills, plentiful sparkling streams, and lush grazing for the local inhabitants cattle. It would not have been an uncommon sight to spot the young boy driving his fathers cattle along the well-worn tracks. Clad in little more than a small blanket draped over his shoulders, whistling or singing and carrying a fighting stick, he would be heading for his mothers kraal and a happy, communal supper with the other youngsters of his extended homestead. It would have been surprising had you known that a lifetime later, the United Nations would proclaim an annual International Day in the name of the boy the first time a person would be so honored.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born in nearby Mvezo village on 8 July 1918. His father was Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa Mandela, a local chief in his own right, but more importantly, an advisor to his cousin, Jongintaba Dalindyebo, the paramount Tembu chief. The Tembu tribe were part of the Nguni people who migrated to South Africa via the Drakensberg in the 11th century. When Mandela was still a baby, his father had a falling out with the local magistrate over a traditional issue, and he was simply stripped of his Chieftainship, and Government stipend as a leader. Having no recourse, Gadla moved his family to Qunu, where Mandela spent a happy boyhood. His mother was Nonqaphi Nosekeni, the third wife of chief Gadla. There were 13 children altogether, and Nelson was the youngest of four sons. He was a descendant of the Ixhiba house and the Madiba clan. He was not destined to rule but, like his father, he would be groomed for the important role of advisor and counselor to the king.

Rolihlahla means the one who pulls branches from the trees; essentially and colloquially, a troublemaker. Mandela greatly admired his father, who was prescient enough to give him such an apt name. In his autobiography, Mandela says he admired his fathers upright posture, which he emulated. Gadla had a shock of thick hair with an unlikely white tuft just above his forehead. Mandela copied this as well by using ash in his hair to create this look. When it was decided that he should attend school, his father cut short the legs of a pair of his trousers which Rolihlahla wore cinched around his waist with string.

The farm school was a single room and on the first day the teacher, a Miss Mdingane, gave him the name Nelson. There was no explanation of why she chose this name; it was just accepted practice in those days of British rule that all black people received English names for the convenience of white people who could not usually get their tongues around traditional names. To a large extent, Nelson also inherited his fathers fierce Xhosa pride and his implacable defense of justice.

There is some dispute about the year his father died: in his autobiography, Nelson says he was nine years old, which makes it 1926, but historical records show it was more likely 1930. What is certain, though, is that it meant a huge change for him, as his father had arranged for him to be taken into the care of his cousin Jongintaba Dalinyebo, the acting Tembu Paramount Chief, and his mother took him to stay at Mqhekezweni, the Great Place. To all intents and purposes, Nelson became, and remained, part of the royal household. He was treated as an equal with his cousin, Justice, and they both attended the same circumcision school when the time came.

Circumcision is the right of passage to manhood and taken very seriously by all concerned. Apart from the surgical act of having the foreskin removed by the appointed circumcision master, the ingcibi, using an assegai, there were lengthy rituals associated with assuming manhood. His coming of age name was Dalibunga, which meant founder of the Bunga, the traditional ruling body of the Transkei. It was also a time of contemplation, which Nelson found quite disturbing. The main speaker at the end of his circumcision celebrations made no bones about the position of black people in South Africa. Chief Meligqili, the son of Dalindyebo, had the following to say: There sit our sons, young, healthy, and handsome, the flower of the Xhosa tribe, the pride of our nation. We have just circumcised them in a ritual that promises them manhood, but I am here to tell you that it is an empty, illusory promise, a promise than can never be fulfilled. For we Xhosas, and all black South Africans, are a conquered people. We are slaves in our own country. We are tenants on our own soil. We have no strength, no power, no control over our own destiny in the land of our birth. The full import of these words might have been diluted in the overall celebratory message, but a seed was planted in the exceptional teenager listening that day. The year was 1934, and the country became the Union of South Africa, a sovereign independent state.

From his privileged position within the royal household, the growing boy was perfectly placed to learn all the intricacies of traditional leadership of a large and diverse tribe. Destined as he was to fulfill the role of royal advisor, he was allowed to observe the inner workings of governance, dispensation of justice, and conflict resolution of the tribal elders. He was also close to Justice, and they were both duly sent to the Clarksburg Wesleyan Methodist Institute in Engcobo to continue their Western schooling. At Clarksburg, Nelson realized that the deference he had come to expect as a member of the royal house no longer applied, and he had to make his own way by his own effort. He was neither a gifted scholar, nor a particularly good sportsman, but he was enthusiastic, diligent, and disciplined, and he did well.

He was then sent to the Healdtown Methodist Boarding school in Beaufort West in 1936, where he and Justice completed their matriculation. At the time Healtown was the largest African school below the equator and had well over a thousand students. It provided a Christian and liberal arts education based on an English model. Dr. Arthur Wellington, the principal, was actually related to the great Duke of Wellington, and nobody was allowed to forget this fact. Nelson did well in the strenuous and demanding milieu. He became very interested in history and took up long distance running. Towards the end of his final year, he had a particularly impressive experience. The great poet and praise singer Krune Mqhayi was invited to speak to the school. Initially electrified by the mans appearance in traditional dress and carrying arms, Nelson was disappointed by his general demeanor and presentation but, nevertheless, deeply impressed by the contents of his speech, which ended with these words: Now, come you, O House of Xhosa. I give unto you, the most important and transcendent star, the Morning Star, for you are a proud and powerful people. It is the star for counting the years...the years of manhood. In his autobiography, Nelson notes: ... as I left Healdtown...I saw myself as a Xhosa first and an African second.