This is a facsimile edition of the original four volumes

The British Press and the Japan-British Exhibition,

compiled and edited by Count Hirokichi Mutsu (1869-1942),

published by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

Transferred to Digital Printing 2010

Preface 2001 Ynosuke Ian Mutsu

Introduction 2001 William H. Coaldrake

Project supervised by William H. Coaldrake

Production managed by Tonia Eckfeld

Melbourne Institute of Asian Languages and Societies

The University of Melbourne

Victoria 3010, Australia.

MMI

ISBN 0-7007-1672-6

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality

of this reprint but points out that some

imperfections in the original may be apparent.

Some Thoughts on the Japan-British Exhibition

by

Ynosuke Ian Mutsu

The aim of the Japan-British Exhibition in 1910 was to spread information about the new Japanese Empire and thereby win friends. It was PR. In 1910 - long before todays Information Age - Japan was little known among the English masses. Mention of Japan called up images of Madam Butterfly of the Italian opera and The Mikado of the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. The works of Lafcadio Hearn were not read widely even in England. London was far away from Japan. A months travel by sea. No air travel yet.

The United States had much to do with the rise and fall of the new Japanese Empire. Americas Black Ships, the steam-powered fleet of Commodore Perry which arrived in Japanese waters in 1852, precipitated a crisis in government which was to bring to an end over 260 years of Tokugawa shogunal rule and the restoration of the emperor. Then a boy of 16, Meiji Tenno became the first Emperor of modern Japan. The imperial court was relocated from Kyoto to Edo, which became the capital of Meiji Japan. The Meiji Constitution reaffirmed the Emperor as the head of Empire combining in himself the rights of sovereignty.

After victories in wars with China and Imperial Russia, Japan gained the status of Empire with colonies in Asia. However, the Empire was later lost during the reign of the Emperor Hirohito. The aggression of the armed forces in China for 15 years could not be held back by Hirohito - although, I believe, he wished to do so. The United States this time came with B29s and dealt massive death from the sky -including atomic bombs - to bring Japan to its knees. The Emperor was not dethroned but was given by the victors his new role of symbol of the state and of the unity of the people in the post-war constitution.

In the days of the Japanese Empire my grandfather, Count Munemitsu Mutsu, sent his eldest son, Hirokichi, to Cambridge, England, for study. There he fell deeply in love with an English girl, Ethel Passingham, who very many years later became my mother.

Legalization of the marriage in Japan had to wait for a long time, after which mother gained Japanese citizenship and became a countess to boot. She took her new Japanese name of Iso, meaning sea-shore. Soon after the marriage, father was assigned to the Embassy in London. I was born in London in 1907, just three years before the Japan-British Exhibition.

As Charge dAffaires at the London Embassy, father, with mothers help, worked assiduously for the success of the Exhibition. My earliest memories that still remain vivid today are of scenes at the Exhibition: people on boats on the pool, paintings of Japanese scenes on the windows of a train, the artificial lake illuminated and other scenes.

Soon after the Exhibition closed the Mutsu Family of three returned to Japan. It was the Expos influence, I believe, that years later made mother write her one and only book Kamakura Fact and Legend, on the shrines and temples of the historic town Kamakura, near the sea, where we had our home. The book, published in 1918, is still selling in its fourth edition.

Father quit the foreign service and set up a large foundation for, among other causes, the spread of Western music in Japan, and the education and elevation of the social position of women in Japan. Mother was a skilled violinist and pianist. The girls school father established, the Kamakura Jogakuin, is now nearing its one-hundredth year and ranks among the best in Japan.

In 1930 - following my mothers death - I returned to Japan after some five years in Birmingham, England, where I had studied music and literature. From the following year on my jobs reflected the aims of the Exhibition: News from Japan for overseas reception. When Pearl Harbour occurred, I was serving as Head of the News for Overseas Department of the Domei News Agency. Soon afterwards I resigned and spent the war years at our villa in the mountain resort of Karuizawa far away from the path of the B29s. Years earlier I had been exempted from military duty because of my foreign looks and background. It was, fortunately, a period of disarmament.

Post-war Tokyo was a pile of ruins. My luck held out and I was given a news-writer job at the United Press Bureau in Occupied Japan. For years news stories under my by-line, on the UPI wire, were distributed and read worldwide.

Soon the Information Age dawned. The written page was augmented by instant audio-visual devices in an increasing number of homes worldwide. After serving as manager for the United States Newsreel Pool, in 1952 I incorporated my own company. Its aim was very much the same as that of the London Exhibition of 1910: to get Japan better understood in foreign lands - only this time on a wider, more global scale. International Motion Picture Company, Incorporated, as I write, is almost in its fiftieth year.

To date IMPC has produced or co-produced with overseas TV companies many documentaries on Japanese themes. For a dozen or so years IMPC served as the BBCs sole agent in Japan for the sale of BBC productions to network TV in Japan. In a curious historical coincidence, the BBCs great centre in London now stands on the former site of the Japan-British Exhibition.

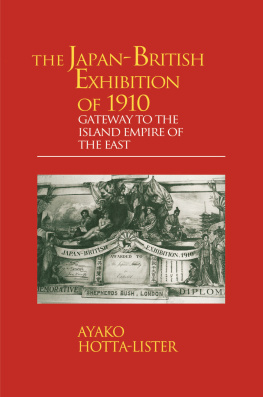

Many legacies of the Exhibition have lived on. A beautiful oil portrait of a British lady by a Japanese painter is now on display at the Shimane Art Gallery in southern Japan. A Japanese woman university graduate recently earned her MA on the Expo. Another Japanese lady, a resident of London, Ayako Hotta-Lister, has gained her doctorate on the Expo and later published her book: The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910.

Years ago, with a crew from IMPC, I spent a week in Kyoto with the late Sir Kenneth Clark while preparing the Japanese language version of his landmark television series