CONTENTS

c.18251900

Artwork by Angus McBride, from MAA 13: The Scythians 700300 BC, by Dr E V Cernenko.

INTRODUCTION

Artwork by Bryan Fosten, from MAA 236: Frederick the Greats Army (1), by Philip Haythornthwaite.

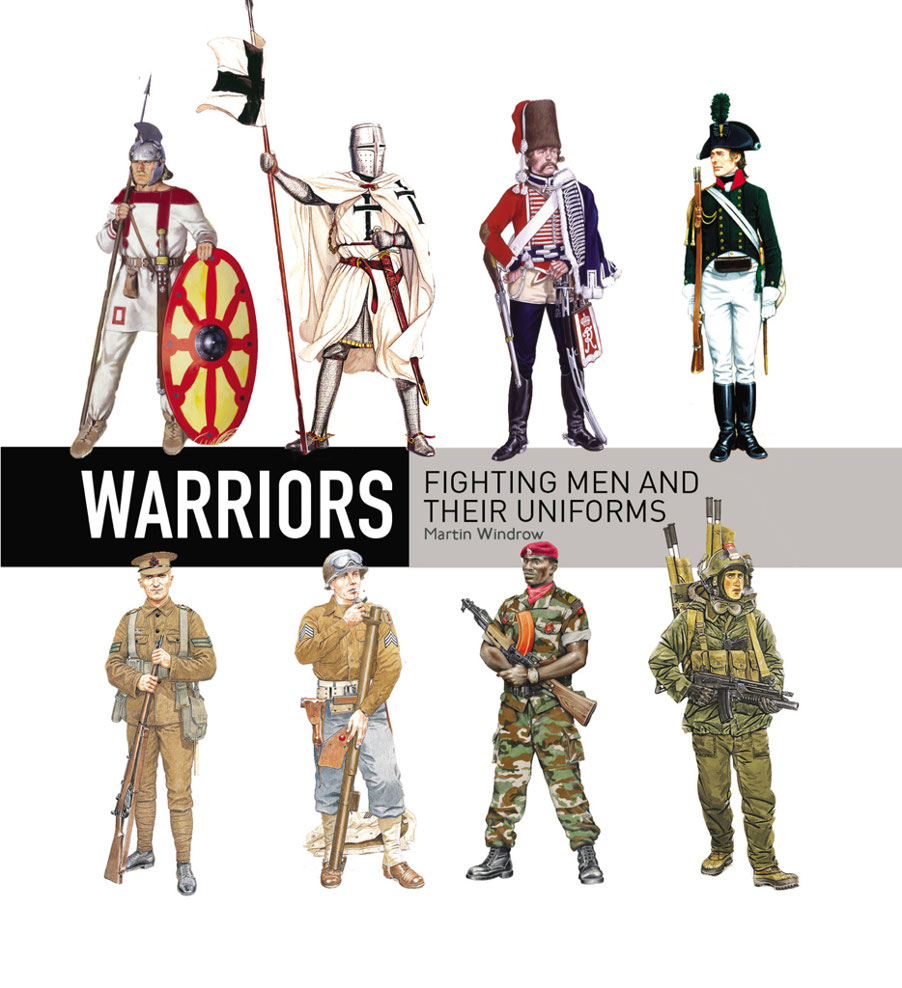

WHAT A SOLDIER WEARS has normally been a practical choice, governed by what weapons he has to face and use, but in many cases martial pride has grown out of practicality. The reason for the birth of true regimental uniforms in the 17th century was essentially practical (central procurement, for a common quality of provision); but wearing similar gear and symbols has always bonded men together, in their own eyes and the enemys. In the 18th century, when the projected narcissism of monarchs produced an orgy of decoration, practicality struck back in the stripped, cut-down uniforms of light infantry skirmishers and the green clothing of Jger riflemen but towering bearskin bonnets and decorated buttonholes were still to be seen in battle a hundred years later.

Practicality also has a way of morphing into decoration: the bunches of laces that secured armour, and the cloth tabs that held cross-belts in place, became ornamental shoulder-knots and epaulettes, and the old Hungarian riders wolfskin cape blossomed into the hussars corded and fur-trimmed pelisse. The hussar exemplified another trend: adopting the outward finery of admired foreign soldiers, as if to acquire their innate military virtues. In the 19th century, Frenchmen copied Turco-Arab zouave costume and Americans copied the Frenchmen.

The new long-range weapons of the late 19th century enforced the change to drab uniforms, but the coloured identifying flashes that had to be added during World War I soon became a source of esprit-de-corps. Late World War II brought separate uniforms for barracks and the battlefield, and the camouflage-printed clothing that represents the ultimate in anonymity. Yet todays soldiers still prefer to be seen in public not in their smart service dress, but in the camouflaged combats that unmistakably mark their calling, individuated by their regimental berets. The Roman legionary, so proud of his military weapon-belts, would certainly understand them.

Any selection of just 100 examples from more than 3,000 years of military history is inevitably fairly arbitrary. Those illustrated have been chosen to show broad trends in Western history, with a few examples to illustrate the widely contrasting nature of other cultures.

Artwork by Angus McBride, from WAR 71: Roman Legionary 58 BCAD 69, by Ross Cowan.

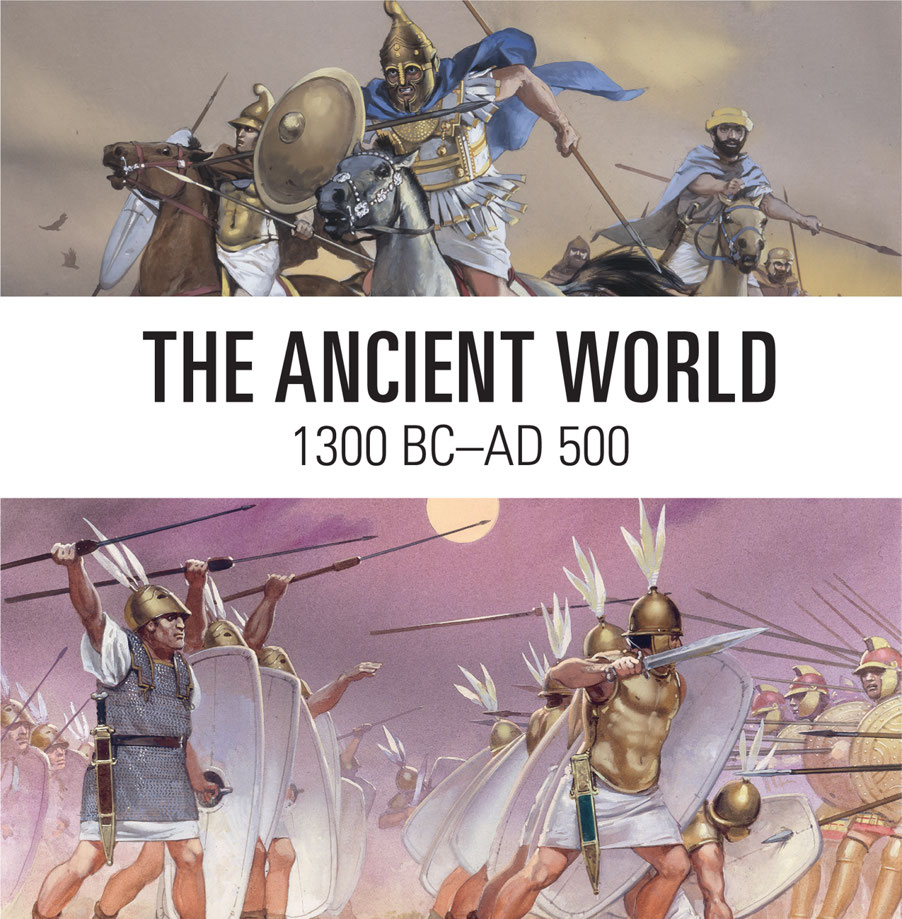

Artwork by Angus McBride, from MAA 360: The Thracians 700 BCAD 46, by Christopher Webber (top); and MAA 291: Republican Roman Army 200104 BC, by Nicholas Sekunda (bottom).

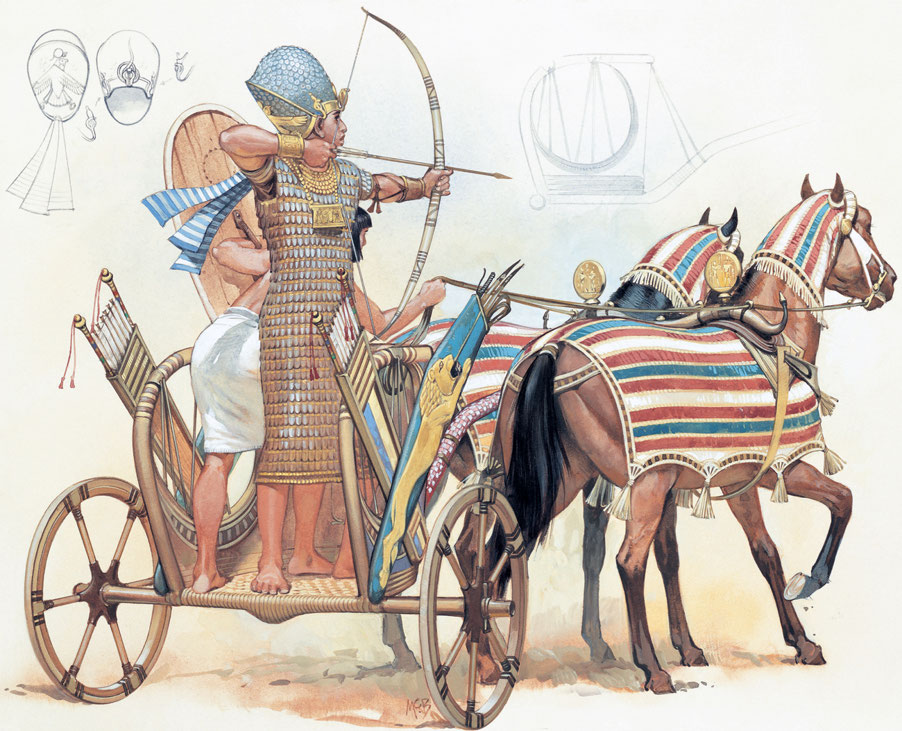

WAR CHARIOT OF PHAROAH RAMESES II

1288 BC

Artwork by Angus McBride, from MAA 109: Ancient Armies of the Middle East, by Terence Wise.

Under the New Kingdom, beginning in the mid 16th century BC, Bronze Age Egypt already had a sophisticated military system. This was based on a rotation of regional contingents to a standing army, supported by reservists, and equipped by central arsenals. Infantry units of common sizes, led by various officer ranks, were formed of spearmen, archers and slingers. The heavy-infantry spearmen fought in disciplined ranks and files, protected by padded cotton body-armour and wooden or wickerwork shields. In addition to spears they carried bronze hatchets or short swords for close fighting.

We base this painting on a depiction of Rameses II charging against the Hittites at Kadesh the first major pitched battle which history records. By the 13th century BC, war chariots formed an important corps within the army; the archers they carried tried to weaken enemy infantry formations at the start of a battle, and enemy chariots tried to thwart them. This initial clash of opposing chariots became ever more important, and the fact that the pharoah himself is shown fighting in this way emphasises the elite status of the chariot arm. The long body-armour of overlapping bronze scales was very time-consuming to construct, and therefore very expensive.

ASSYRIAN MOUNTED ARCHER

7TH CENTURY BC

Artwork by Angus McBride, from MAA 109: Ancient Armies of the Middle East, by Terence Wise.

By the late 8th century BC the Assyrians of Mesopotamia were the leading regional power. Expanding ruthlessly, they sacked Babylon in 689 BC, and invaded Egypt in 670 BC. In 612 BC they would finally be defeated in their turn, by the Babylonians and Medes.

This painting depicts a horse-archer fighting more primitively equipped Arab camel-riders during the reign of the great King Ashurbanipal (668627 BC). The bulk of the army was always infantry, but it probably had a ratio of about one heavy chariot (now with a three-man crew) and ten cavalrymen (with bows and lances) for every 100 spear-armed footsoldiers. Apart from being highly organized, Assyrian armies enjoyed one other great advantage mastery of iron, harder and sharper than bronze. By the reign of King Sargon II (721705 BC) his army was widely equipped with iron weapons and helmets, though the lamellar armour illustrated here (i.e. of metal strips sewn side-by-side and end-to-end on a base garment) is still bronze. The horse-trapping is also probably padded to give some protection against arrows. The horse-archers bow is of composite construction made by fitting and gluing together sections of wood, bone and sinew, which gave superior power and range.

Horse lancer of the Assyrian cavalry, 655 BC. Artwork by Angus McBride, from ELI 39: The Ancient Assyrians, by Mark Healy.

SCYTHIAN NOBLES

5TH CENTURY BC

Artwork by Angus McBride, from MAA 137: The Scythians 700300 BC, by Dr E V Cernenko and Dr M V Gorelik.