I LLUSTRATIONS

President Richard Nixon and National Security Adviser Dr Henry Kissinger, 1972. White House Photo Collection.

National Guardsmen advance towards student protestors at Kent State University, May 1970. Kent State University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives.

Nixon mingles with anti-war protestors at the Lincoln Memorial, May 1970. Getty Images.

West German Chancellor Willy Brandt kneeling at the Warsaw Ghetto memorial, December 1970. Getty Images.

Richard and Pat Nixon at the Great Wall of China, February 1972. US National Archives and Records Administration.

Nixon and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai share a toast, February 1972. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Kissinger briefs the White House press corps that Peace is At Hand in Vietnam, October 1972. Shutterstock.

Kissinger and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev hunting outside Moscow, May 1973. Getty Images.

Nixon and Brezhnev en route to California aboard presidential aircraft Spirit of 76, along with Treasury Secretary John Connally and interpreter Viktor Sukhodrev, June 1975. US National Archives and Records Administration.

Brezhnev and interpreter Sukhodrev meet actor Chuck Connors at San Clemente, California, June 1975. US National Archives and Records Administration.

Nixon, Kissinger, Alexander Haig and new vice-president Jerry Ford in the White House, late 1973. Getty Images.

Premier Golda Meir and Defence Minister Moshe Dayan visit Israeli troops on the Golan Heights after the Yom Kippur War, November 1973. Getty Images.

Writers Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Heinrich Boll meet after the formers exile from the Soviet Union, February 1974. Associated Press.

Nixon hugs his daughter Julie after announcing his resignation watched by sister Tricia and husband David, August 1974. US national Archives and Records Administration.

President Jerry Ford swaps his fur coat with Brezhnev, Vladivostok Summit, December 1974. Associated Press.

Fleeing Americans board a US Marine Helicopter at Tan Son Nhut Airbase in Saigon, Vietnam, April 1975. Getty Images.

P REFACE

Its subjunctive history, Hector tells his pupils in Alan Bennetts The History Boys. You know, the mood used when something may or may not have happened. Some periods in time seem decisive, clear-cut. My first book, Aftermath, was about such an era, with the Second World War and onset of the struggle between East and West which followed it. This second volume picks up that story two decades later, in the middle passage of the Cold War. Beginning with the summer of 1968, when Soviet tanks quelled the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia, and the Democratic Party convention in Chicago collapsed amid scenes of popular protest at the Vietnam War, the book runs through to 1975, with Americas final exodus from Saigon, and the twilight period of Jerry Fords caretaker presidency.

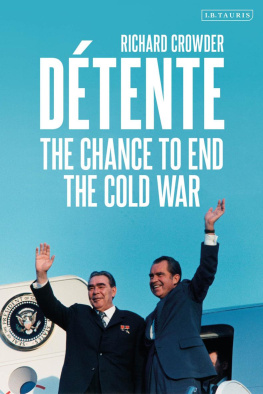

During these seven years, the world changed, and yet didnt. The leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, hoped to forge a new relationship between East and West. An era of negotiation, rather than confrontation, as Nixon called it, for which Brezhnev coined the name dtente a French word for an easing of tension, which had first entered the diplomatic lexicon to describe failed efforts to defuse competition between the great powers before the First World War. The quagmire of Vietnam and the strain of the Czechoslovakia invasion had forced both men to question old thinking, and wonder whether it might be possible to channel the Cold War away from the brink of conflict, towards a peaceful coexistence, in the phraseology of the time. In parallel, Nixon reached out to communist China, in a dramatic break with her isolation over the previous decades. And, within Europe, West German leader Willy Brandt imagined a new start for his country, burying the shame of the Nazi past in a reconciliation with her Eastern neighbours that was dubbed Ostpolitik.

Dtente was not to be. The high point came in 1972, with a first visit for Nixon to Moscow, close behind his trip to Beijing. Nixon and Brezhnev signed agreements on limiting nuclear weapons and other matters, posing for the worlds cameras with champagne glasses in hand. But by 1974, when Nixon returned for a second visit amid tumult in Washington over the Watergate affair, it was clear that the initiative had run its course. Dtente limped on through the subsequent presidency of Jerry Ford, with agreement of the Helsinki Accords on peace and human rights in Europe, and enjoyed a brief revival under his Democrat successor Jimmy Carter. With the arrival of Ronald Reagan to the presidency, a new chapter opened in the Cold War, and a dramatic return of tension between the superpowers. Dtente fell apart for many reasons lack of support in both countries; geopolitical tensions, including in the Middle East; Nixons own political demise. At its core, it failed because it assumed that the superpowers could park differences in their values to work on common interests. That tension whether voiced by the neoconservative hawks in Washington or dissidents under persecution inside the Soviet Union made long-term cohabitation impossible.

There is much tactical mastery during this period to admire. Nixon and Kissinger were players at the top of the game, drawing together different threads nuclear talks; agreement over Berlin; Middle East; Vietnam; China to pursue their goals. It was diplomatic tradecraft of the highest order, if cynical and secretive at the same time. The channel between Kissinger and Anatoly Dobrynin, the wily veteran who served as Soviet ambassador in Washington, was a thrilling blend of intellect, battle of wits, and moments of genuine friendship. In the closing months of Nixons presidency, the shuttle diplomacy that Kissinger conducted in the Middle East after the Yom Kippur War is another case study in first-class diplomacy, as he coaxed historic adversaries towards a path of peace.

Dtente left some important traces. The agreements on missile defence and limiting strategic arms that Nixon and Brezhnev signed have, until recently, been a bedrock to international arms control. The Helsinki Accords enabled creation of groups like Solidarity in Poland or Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, whose opposition to communism eventually led to the revolutions of 1989 in eastern Europe. Nixons opening to China paved the way for the reforms that unleashed the Chinese economy as a global powerhouse. As we look at this wall, commented Nixon during his visit, what is most important is that we have an open world. Fifty years on, that has come true in ways unimaginable at the time, as people, information, finance and ideas swirl around our planet at a speed and with consequences that we sometimes find hard to comprehend.

Yet, the greatest changes of the era took place outside the sphere of international diplomacy. The 1960s brought social collision across the world, from the anti-war protests in America to the student demonstrations on the streets of Paris, or Mao Tse-tungs Red Guards in China. A new generation, whom advertising executives dubbed the baby boomers, brought new attitudes. Musicians of the era Bob Dillon, Jimmy Hendrix, John Lennon preached a new set of values, and attitudes towards sex, gender, race, the environment and religion were all transformed. The landmark ruling on abortion,

![Kissinger - Years of Upheaval: [VOL2 Classic Memoirs]](/uploads/posts/book/181244/thumbs/kissinger-years-of-upheaval-vol2-classic.jpg)