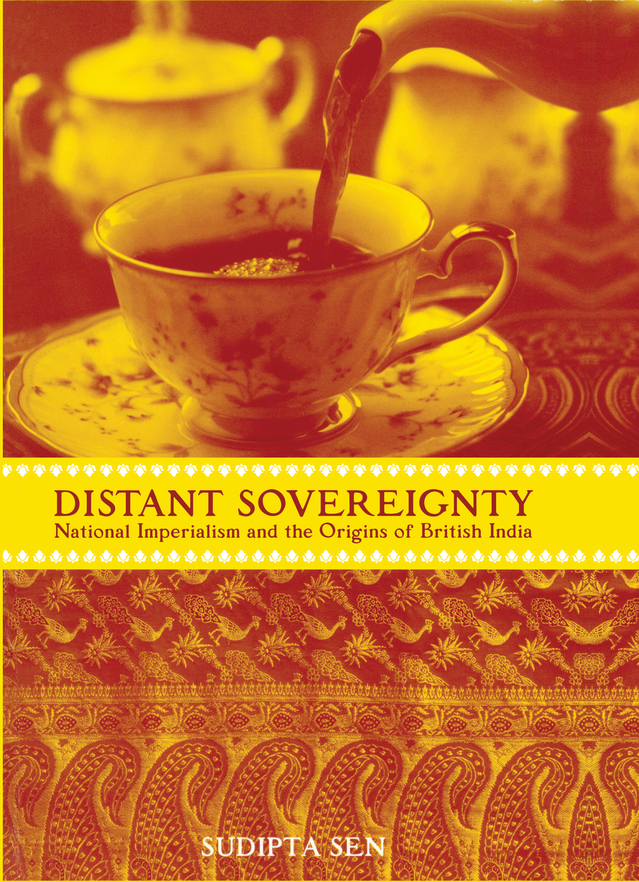

DISTANT SOVEREIGNTY

Distant Sovereignty

National Imperialism and the Origins of British India

Sudipta Sen

Published in 2002 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Copyright 2002 by Taylor & Francis Books, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

Distant Sovereignty / Sudipta Sen

ISBN 0-415-92953-9ISBN 0-415-92954-7 (pbk.)

For Phil Corrigan

Contents

This book owes its origins to the friendship and encouragement of members of the Discussion Group on the Formation of the English State, St. Peter's College, Oxford University, where I first presented a paper in April 1993 at the insistence of Bernard Cohn. My introduction to the group and subsequently to the Journal of Historical Sociology ( JHS ) seems in retrospect, to have been a catalytic experience, in the sense that it forced me to consider the history of colonial India in the light of the domestic history of England and come to terms with an archival methodology that has lately been christened as the "new imperial history." There is nothing here that is particularly radical in this for those of us who had the privilege to work with Barney Cohn, who had almost single-handedly initiated this mode of inquiry for an entire generation.

I am also indebted beyond words to Philip Corrigan for his amazing generosity, his critical eye, and his bibliomania, all which have enriched my life as a historian and as a human being ever since I met him. I wish to thank others associated with the Oxford group and the JHS, especially Derek Sayer, Gavin Williams, Joanna Innes, Martha Lampland, Bruce Curtis, John Gillingham, Sir Gerald Aylmer, and Daniel Nugent; it is indeed difficult to accept that the last two are now no more. I would also like to thank here a mentor from my student days in Calcutta, Rudrangshu Mukherjee, who introduced me to the history of England and urged me towards further exploration of colonial Indian history. Among friends who have helped to sustain my interests over the years, I cannot forget Antoinette Burton, Philippa Levine, and Faisal Devji. Others who have directly or indirectly commented on aspects of this work are Uday Singh Mehta, Thomas R. Metcalf, Elizabeth Helsinger, Jean Comaroff, Paul Jaskot, Ian Barrow, Urmila De, Jeremy Black, Mary Poovey, Richard Cullen Rath, Michael Fisher, Durba Ghosh, Prasannan Parthasarathi, Paul Greenough, Gautam Bhadra, Barun D, Sanjay Srivastava, and Kevin Grant. Research for this volume was conducted at the Oriental and India Office Collections at the British Library, the Widener Library at Harvard University, the Bird Library Special Collections at Syracuse University, the Olin Library at Cornell University, and the West Bengal State Archives at Kolkata. A special note of thanks goes to Susan Bean and the staff of the Duncan Philips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, where, searching for something quite else, I stumbled upon some of the printed pamphlets discussed here. I do not have the space here to acknowledge all the conferences and venues where I have presented various chapters and sections of this book. I must thank, however, the following for agreeing to the publication of revised versions of articles in this book: the JHS and South Asia (the South Asian Studies Association of Australia).

Thanks are also due to Minara Mollah for her detective work with footnotes and bibliography and to Vik Mukhija for his helpful editorial interventions and remarkably friendly policing of deadlines; finally, my gratitude to L, D, and M for putting up with the research and writing of this book.

Restoring the Mughal Empire

By the summer of 1813 it had become clear to residents of Delhi and to observers of public affairs in northern India that the great Mughal emperor had been made a virtual prisoner on his throne by the British. In that year the dowager queen and the heir apparent had traveled east to seek the counsel of Awadh, a provincial regime humbled by the East India Company, in the dispute that was brewing over royal succession. The Company did not approve of the emperor's choice of prince regent and took exception to the fact that the prince had deceived the British Resident by pretending to attend a wedding and by falsely claiming that the governor-general in Calcutta had issued leave for their travel. The Company found these actions "disgraceful" and in subsequent letters of complaint accused the royal family of having brought "injurious insinuations against the justice and liberality of the British government"; it also reprimanded the emperor on his behavior in the matter of succession to the throne as a sign of his "ingratitude and deceit."

After the Battle of Delhi in 1803, in which the Marathas were repulsed, the emperor had all but surrendered to the British forces. The facts that he was financially beholden to the East India Company, confined to the walls of the Red Fort, its court, and its bazaar, did not retain regular troops in his pay, and required written permission of the British Resident to move about freely were a testimony to the undeclared political mastery of the British at the heart of the subcontinent. But it is also clear that the British were eager to preserve remnants of the Mughal empire and the royal family as a necessary bastion of their newly acquired territorial and military power. They viewed themselves in this capacity as a "subject of jealous observation" by other potentially hostile states and chieftains in India and did not wish to Enemies abounded near Delhi and across the northwest; the Marathas still roamed free in the countryside.

The aura of the Mughals would continue to haunt the political climate of northern India for a long time to come. Any association to Delhi in the eighteenth century was a valuable tool for aspiring regimes and military fortune seekers. Lord Lake, the British commander who had retrieved Emperor Shah Alam in 1803 from dangerous collusion with the Maratha chief Daulat Rao Sindhia (who was advised by the French), considered the Mughals as integral to the future security of British possessions on the northwest frontiers.

The political relationship between the British in India and the ruling house of Timur continued to be fraught with inconsistency and ambiguity in subsequent decades. The contradictions of legitimacy would be resolved only after the mutiny and rebellion of 1857, when the last emperor, Bahadur Shah, was tried as "a subject of the British Government in India," and a "false traitor against the State" who had proclaimed himself as the "reigning King and Sovereign of India" and taken "unlawful possession" of the city of Delhi.Bihar, and Orissaa windfall that bailed out its monopoly tradein exchange for an annual tribute of 26,00,000 rupees.