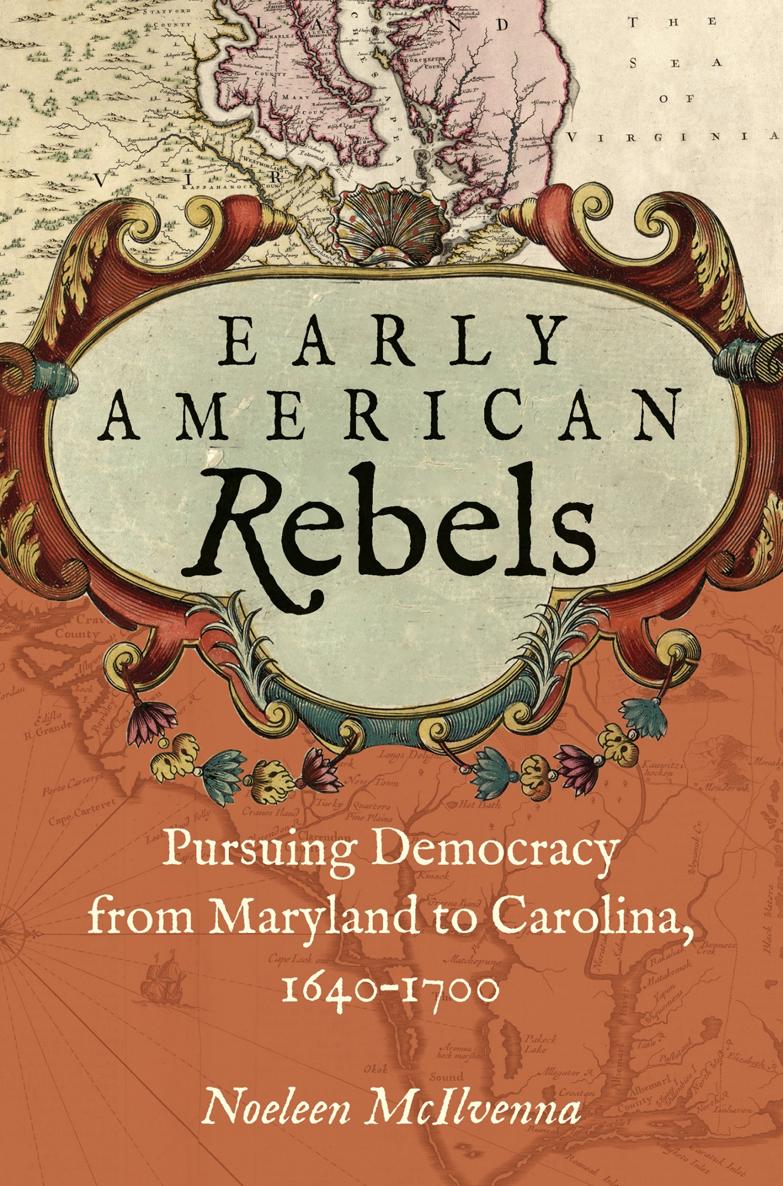

Early American Rebels

Early American Rebels

Pursuing Democracy from Maryland to Carolina, 16401700

Noeleen McIlvenna

The University of North Carolina PressCHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Fred W. Morrison Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2020 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McIlvenna, Noeleen, 1963 author.

Title: Early American rebels : pursuing democracy from Maryland to Carolina, 16401700 / Noeleen McIlvenna.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019044426 | ISBN 9781469656052 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469656069 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469656076 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Representative government and representation United StatesHistory17th century. | InsurgencyUnited States History17th century. | DemocracyUnited StatesHistory 17th century. | United StatesHistoryColonial period, ca. 16001775. | Great BritainColoniesAmericaHistory.

Classification: LCC E188 .M17 2020 | DDC 973.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044426

Cover illustrations: Top, Christopher Browne, A New Map of Virginia, Maryland, and the Improved Parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey (courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division); bottom, John Speed, A New Description of Carolina (courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection, http://www.davidrumsey.com).

To Lance

Contents

Figure and Maps

FIGURE

MAPS

Acknowledgments

My thanks go first to Stephen Jenkins and to Billie Jenkins, genealogists who provided essential leads at the beginning of my research. I hope they understand why the book became much more than the story of John Jenkins.

I am truly grateful for the financial support from the North Caroliniana Society, who awarded me an Archie K. Davis fellowship. Wright State University support also proved crucial; funding from the College of Liberal Arts allowed travel to archives from Annapolis to London. During those travels, archivists at the Maryland State Archives, Maryland Historical Society, and the Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture were consummate professionals. Librarians at Duke University and North Carolinas State Archives, at the Alderman Library, University of Virginia and the National Archives in London also eased the pain of research.

Readers improved the book a great deal, and I am thankful for their thorough feedback. The UNC Press editorial staff are patient with me, and Chuck Grenchs relentless positivity sustains a writer over the long, long years of writing a book.

Good colleagues make everything possible. My writing group, a troop of dedicated women, sat at tables with me for years, ensuring I never gave up. Carol Mejia-Laperle, Sirisha Naidu, Marie Thompson, Nimisha Patel, Sarah Twill, and especially Deborah Crusan, who fed me nearly every week while I slowly produced these pages, have my undying loyalty. And while I tried to describe the struggles of the Gerard network for self-rule, I learned in real life what it took to maintain a coalition against power. My fellow AAUP-WSU officers reminded me why the work of academics matters so much to a free society, and the facultys collective struggle for the soul of the university over the last several years illuminated the truth that perseverance is militancy. I am forever inspired.

My familys faith in and patience with me through the production of three books deserves a major award. Tess models scholarly discipline for me, instead of the other way around. My partner, Lance Greene, taught at universities in other states while I wrote this one. He came back though, and as always, made the figures and formatted the text. But his ongoing contribution is so much more. His intellectual company challenges my thinking. His steadfastness and love allow me to work from a firm foundation. The book is dedicated to him.

Early American Rebels

Introduction

We are about to meet some of the most determined egalitarians in American history. The household of the first Susannah Gerard of St. Clements, Maryland, would nurture both ideas and action profound for their time. Informed by experiences, and demanding some say in their own destiny, men and women moved around the Chesapeake region, looking for a means to build a political system that would serve their needs. That they maintained the struggle over a half century, spread over at least three colonies, and managed to be elected again and again by their neighbors allows us to see that they were not a fringe movement, but in fact, leaders who brought modern ideas into the mainstream, only to face repression. Yet they won battles, and some seemed to win the war in their own lifetimes. This story of political radicals in the seventeenth-century colonies might have been told as an intellectual history, tracing the shifts in thought over time between republicanism, democracy, and equality before the law, while disentangling the knots between religious theology and the spectrum of political radicalism. But because these people were not intellectuals in the normal usage of the term, but in fact activists, this is a political historya history of class struggle.

The struggle occurred at a particular moment in the development of global capitalism, a stage economists usually call primitive accumulation. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, the lords of the manor were enclosing their lands in high hedges, forcing peasants to the cities and replacing them with more lucrative sheep. For a century, an unemployed rural proletariatlandless laborersexisted in England. In time, the wool constituted the raw materials and the unemployed peasants the labor that joined together in the workshops built by early industrialists. The profits their work generated would become the capital that could finance the ever larger factories, mills, and mines generating ever more capital for ever more development. In the American colonies, however, the process differed. Europeans violently expropriated the land not from feudal peasants but from Indians. Then, unfree workersat first indentured servants bound for years to work without pay, and later enslaved people kidnapped from Africa and their children born into slaveryperformed the labor. The system did not match our normal vision of an urban working class toiling for poverty wages in a textiles factory. These laborers performed their work instead in tobacco and cotton fields, on rice and indigo plantations. But the resultthe creation of massive capital and political power in the hands of a fewwas the same. This process took about a century in the area around the Chesapeake Bay.

At this primitive accumulation stage, the term class was not what it became after the Industrial Revolution. In the British realm of 1600, the dominant concept was blood or kinship hierarchy. Accident of birth determined the limits of the possible. The child of the king, the child of the country squire, the child of the yeoman, and the child of the peasant knew their place. The top 5 percent, nobility and gentry, expected that all in society would behave accordingly, accepting without protest the parameters of power for their social rank. Every institution in society undergirded this reality, not least of all the Church of England. A glimpse at a wedding of an heir to the British throne takes us back to a time when the monarchs position at the front of the church reflected their position in society, and the rest filed into their pews in the social order of their birth. This hierarchy thus seemed to an uneducated populace to be endorsed by God, and the church/state censorship ensured that any critical thinking of the premise would not find an audience. It had been this way for centuries, and the trappings of pomp and mysticism encouraged all to believe that no alternative existed.