First published in 1936 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

This edition first published in 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1936 George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781138482739 (Set)

ISBN: 9780429455360 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 9781138316720 (Volume 10) (hbk)

ISBN: 9780429455438 (Volume 10) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

KEY ECONOMIC AREAS

IN CHINESE HISTORY

AS REVEALED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF

PUBLIC WORKS FOR WATER-CONTROL

BY

CHAO-TING CHI

[1936]

TO

HARRIET

WITH

LOVE, RESPECT AND GRATITUDE

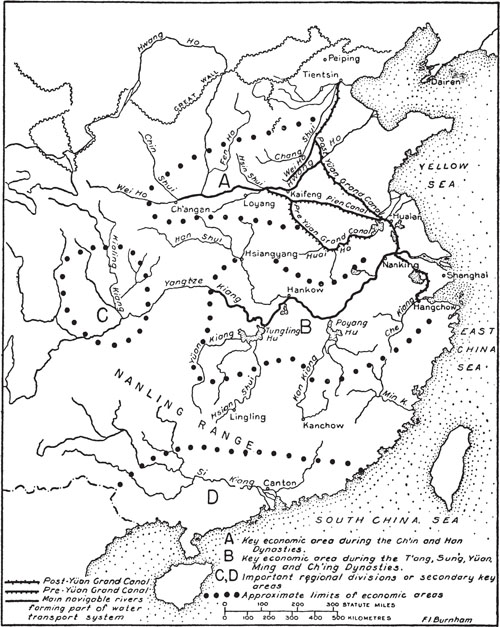

T HE present work offers the conception of the dynamics of the Key Economic Area as an aid to the understanding of Chinese economic history. By tracing the development of the Key Economic Area through an historical study of the construction of irrigation and flood-control works and transport canals, it aims to show the function of the Key Economic Area as an instrument of control of subordinate areas and as a weapon of political struggle, to indicate how it shifts, to reveal its dynamic relation to the problem of unity and division in Chinese history, and to give, on the basis of this approach, a concrete and historical-descriptive analysis of one phase of the economic development of China. The book does not purport to give a new interpretation of Chinese history as a whole. However, if the concept of the Key Economic Area proves helpful to the solution of one of the fundamental problems in Chinese history, it cannot but affect the understanding and interpretation of the whole process of Chinese historical development. In order to place this theory in its proper perspective and to indicate its possible extension and further application, it is perhaps better at this point for the author to state his general approach to historical economic studies in China.

Man makes his own history, not only under conditions which history hands down to him, but also through the rewriting of past history. This is because history itself is historical and can only be understood by each epoch, and be of service to it, in the light of its own experience. New experience gives rise to new historical insight, and in the light of new understanding, new problems can be formulated, old and new evidence resifted, and significant facts selected out of a multitude of seemingly meaningless data. Thus history must be continually rewritten in order to answer the need of man in each specific epoch. The rewriting of history is part of mans efforts to harness the forces of history, and this task becomes particularly urgent at each turning point in the historical process.

Ever since the opening of China in the middle of the nineteenth century, the problem of rewriting Chinese history has loomed large on the intellectual horizon not only of China, but of the whole world. Capitalist foreign trade and investment, through its exploitation of the world market, has created an interdependent world economy and has thrown the unevenly and differently developed socio-economic set-ups of various peoples into one turbulent current of world history. Chinese history is no longer the history of just one country, but it has merged into the stream of world history. Western institutions have made serious inroads into Chinese life, which, in turn, has become an important factor in the life of the West The far-reaching consequences of the situation were epitomized in the Great Revolution of 19251927 and its subsequent developments, which brought to the fore, for the first time in centuries, the most fundamental problems of the dynamics of Chinese society.

Economic history, or dialectical economics, recognizes the fact that fundamental problems of China to-day cannot be understood merely by studying contemporary conditions, but must be approached historically through attempts to solve the basic questions of Chinese history raised by the demands of our epoch, and to discover the dominant tendencies which govern the development of Chinese economy. The main objective of such a study, of course, is historical and socio-economic synthesis.

But synthesis and analysis are two phases of the same process and cannot be mechanically separated. Synthesis signifies building up or organization, while analysis means breaking down or separation. But, since both exclude chaos, and wanton behaviour, it is clear that building up is impossible without first having broken down and understood the meaning of the parts, and it is equally true that taking apart is impossible without first having an idea of how the parts are put together. Applying this principle to historical writing, it means that synthesis involves the systematic merging of leading ideas which result from analytical study of special problems, while analysis cannot be fruitful without a general approach to guide its labours in working through a maze of otherwise meaningless data. The apparent contradiction between the two concepts is really a reflection of their dialectical relationship; both represent necessary phases of the same process of scientific investigation. A book may be primarily a work of synthesis or of analysis, but an investigation can be fruitful only when the intimate connection between the two concepts is expressly or tacitly recognized.

Although the final purpose of the authors study of economic history is synthesis, the present book is primarily a work of analysis. It began as an attempt to trace the development of irrigation and flood-control in Chinese history through an analytical study of the immense amount of untouched source material on the subject hidden in the gazetteers (local historical geographies), special Chinese works on water benefits, and the dynastic histories. The general direction of the authors researches naturally has been determined by his preconceptions and general method of approach, specifically by his realization of the importance of irrigation and water transportation in Chinese history. But it was only after a close examination of most of the available material in the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., that the belief in the importance of water-control to Chinese history was confirmed and the conception of the Key Economic Area and its relation to unity and division in Chinese history developed in the authors mind. This book as it stands, which, except for minor changes, was completed in the middle of April 1934, represents the authors preliminary effort to define the concept, to study the geographical basis for water-control and economic regionalization in China, and to trace briefly the shifting of the Key Economic Area in Chinese history.