Quarterly Essay is published four times a year by Black Inc., an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Publisher: Morry Schwartz

ISBN 186 395 1342

ISSN 1832-0953

Subscriptions (4 issues): $49 a year within Australia incl. GST (Institutional subs. $59). Outside Australia $79. Payment may be made by Mastercard, Visa or Bankcard, or by cheque made out to Schwartz Publishing. Payment includes postage and handling.

To subscribe, fill out and post the subscription card, or subscribe online at:

www.quarterlyessay.com

Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to the Editor at:

Black Inc.

Level 5, 289 Flinders Lane

Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia

Phone: 61 3 9654 2000

Fax: 61 3 9654 2290

Email: quarterlyessay@blackincbooks.com

Editor: Chris Feik

Management: Sophy Williams

Production Co-ordinator: Caitlin Yates

Publicity: Meredith Kelly

Design: Guy Mirabella

Printer: Griffin Press

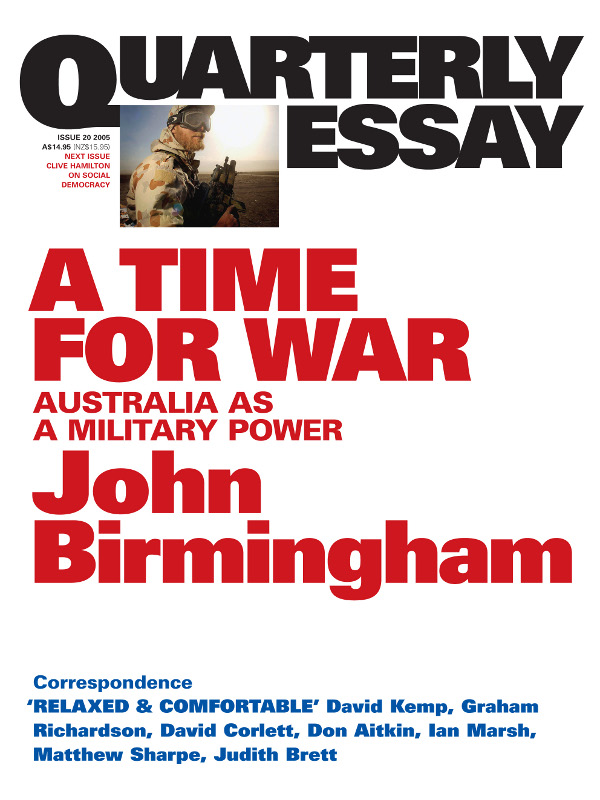

A TIME

FOR WAR

Australia as a

Military Power

John Birmingham

Once upon a time every schoolboy in the British Empire could tell you about the Afghan wars. Be they seated at a small wooden desk in Liverpool, Calgary, Dunedin or Toowoomba, they could take their Conway Stewart fountain pens and scratch out a couple of paragraphs on, say, the massacre of nearly seventeen thousand men, women and children during the British retreat from Kabul, through the Khyber Pass in January of 1842.

Those fortunate enough to attend a better school could probably provide some context, pointing out that the passes of the eastern reaches of the Hindu Kush had run deeper with blood than water at many times in the previous three and a half thousand years. Invaders from central Asia and Europe had repeatedly swarmed down the mountains and into the fertile plains of the Indus River valley since Alexander the Great hacked and slashed his way through in 326 BC. Genghis Khan and Tamerlane, two of the great warrior-psychopaths of human history, brought their version of shock and awe to the defiles in 1224 and 1398. Muslim hordes under Mahmud of Ghaznawi poured through up to seventeen times between 1001 and 1030 AD.

So many conquerors, invaders, brigands, savages, slavers, liberators and true believers of one kind or another have contended in blood in this place that it is a wonder the ground remains so barren. With so much life having been spilled over the centuries by Persians and Scythians, White Huns, Tartars, Mongols, Mughals, Soviets, British and Americans, its a minor mystery how the fallen cannot have nourished the earth with their passing. But barren it remains.

The 800-kilometre-long mountain system was born of the tectonic clash between the Indian and Eurasian plates. The rocky granite of the jagged, broken-tooth landscape is largely igneous metamorphic in origin, a coldly scientific term for the hellish processes involved in generating enough heat and pressure to turn solid rock molten and lift it up into a summit twenty-five thousand feet high. Here and there on the northern slopes forests are sustained by snowmelt; wild goats and sheep and even small remnant populations of black and brown bear are to be found tucked away in the high crags. But for the most part the whole area presents to European eyes as desolate howling wasteland.

The sorrows of history and terrain have created a crazy maze of ethnic splinters and tribal groups, some of which can boast of blood feuds nurtured through many, many centuries. To these micro-states there have recently been added new bloodlines from all over the Dar al-Islam as jihadi flowed into Taliban and Al Qaeda training camps through the last years of the twentieth century.

Civilisations have always ground against each other in this stark landscape. For glory, for treasure, for no good reason beyond the Great Khans belief that the greatest joy a man can know is to conquer his enemies and drive them before him.

The modern Afghan wars have been fought for purposes high and low. The first, disastrous British expedition, which ended in the slaughter of General Elphinstones force by Ghilzai warriors in the gorges between Kabul and Gandomak, touched off nearly a century of strategic rivalry with the Russian Empire for control of Afghanistan. The Soviet invasion of 1979 can even be seen as a continuation of this, as the Tsars successors manoeuvred to gain greater access to the choke-point at the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Alternately it may have been a pre-emptive strike, to snuff out the possibility of an Islamist revolt such as occurred in Iran. Whatever the case, Leonid Brezhnevs generals were no more successful than Queen Victorias had been, and the Red Armys tenure left only ruins from which the Taliban emerged as the avatars of an older, apocalyptic vision of war as a holy calling.

To this long trail of tears one more people sent their warriors. They were Australians, and in the first weeks of March 2002 they fought a battle in a valley known as the Shahikot.

When a hundred SAS troops infiltrated the heights overlooking the Shahikot, they were the first ground forces this country had committed to major combat since the early 1970s, when the Royal Australian Regiment was fighting in Vietnam. The intervening years had seen great change, both in the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the society it was pledged to protect. The Australians who served in Vietnam from 1962 were a mix of volunteers and draftees. They did not enjoy the unqualified support of the citizens in whose name they fought, and many were vilified on their return.

The fracturing of Australian society that accelerated throughout the 1960s was driven in part by increasingly vehement disagreement over the Vietnamese conflict. The intricate skein of blood and consequence spun out of that war is far too complex to untangle here, but a few strands stand out. A generation, or at least a significant part of it, was to some extent radicalised. Australian governments lost confidence in the use of military force as an instrument of policy. And in combination, these developments created a substantial body of mass and elite opinion that came to doubt and even deny the legitimacy of military force.

No Commonwealth government, not even Gough Whitlams, seriously considered embracing pacifism or the tenets of unilateral disarmament. But a broad-based coalition within civil society did coalesce around a loose, ill-defined set of principles that might best be characterised as anti-war. The peace movement had no formal leadership or organisation, but it did have demographic weight, drawing hundreds of thousands of disparate individuals into public action, for instance during the Vietnam Moratorium marches, or a decade later in the anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1980s.

The end of the war an ignominious defeat for the industrialised democracies saw the retreat of the military from the centre of public life in Australia. It had been damaged by the misadventure in South-East Asia. While Australian soldiers proved more than a match for the North Vietnamese regulars and Vietcong guerillas against whom they fought, at home the armed forces lost their standing as a universally respected institution. The nations military heritage as important a part of the culture as trade unionism, liberal individualism, the bush, sport or more recently multiculturalism was devalued in the eyes of a large minority of the population. Importantly, because so much of the most uncompromising and aggressive opposition to the war had originated on university campuses, a large cohort of future leaders was estranged from the military tradition that had, just one generation earlier, secured the very freedoms the protesters enjoyed while opposing the war.