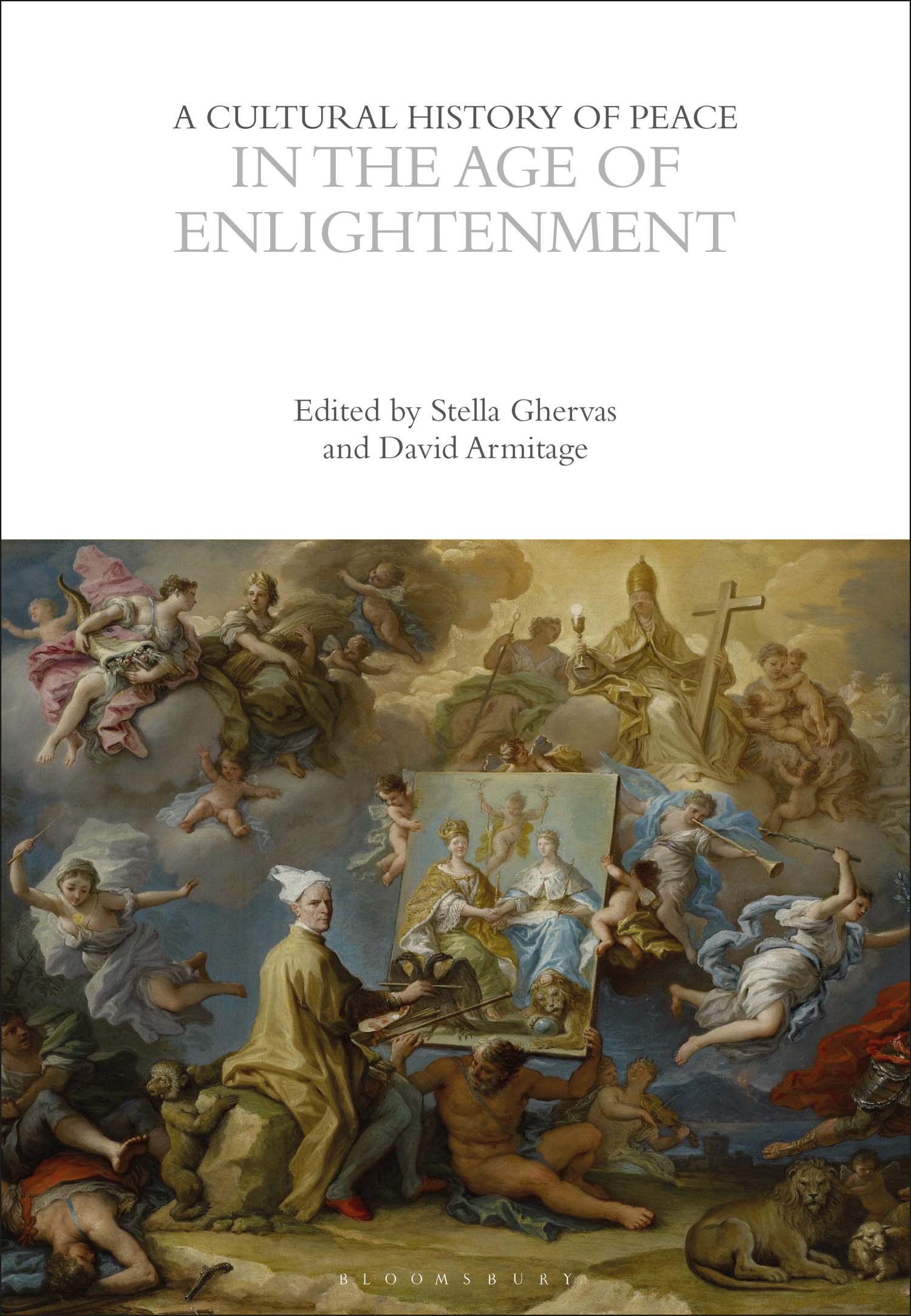

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF PEACE

VOLUME 4

A Cultural History of Peace

General Editor: Ronald Edsforth

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Peace in Antiquity

Edited by Sheila L. Ager

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Peace in the Medieval Age

Edited by Walter Simons

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Peace in the Renaissance

Edited by Isabella Lazzarini

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Peace in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Stella Ghervas and David Armitage

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Peace in the Age of Empire

Edited by Ingrid Sharp

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Peace in the Modern Age

Edited by Ronald Edsforth

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Immanuel Kant (17241804).

Theodor van Thulden, Allegory of Peace and Justice after the Thirty Years War.

After Gerard ter Borch, The Ratification of the Peace of Mnster (1648).

Hugo Grotius (15831645), Dutch Jurist and Politician.

Delff, The Signing of the Treaty of Utrecht on 11th April 1713.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (17121778).

The Congress of Vienna (1815).

CHAPTER 1

Henry Sumner Maine (18221888).

Eirene, Goddess of Peace.

Christian Wolff (16791754).

Benjamin Constant (17671830).

CHAPTER 2

Frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes De Cive (Paris, 1642).

CHAPTER 3

Pierre Mignard, Alexander the Great and Thalestris, Queen of the Amazons.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (16241674).

John Opie, Mary Wollstonecraft.

CHAPTER 4

Thomas Hobbes, 1676.

Jonathan Swift, The Tale of a Tub (1721).

George Fox preaching to a crowd in Maryland (1671).

Benjamin West, William Penns Treaty with the Indians (177172).

Immanuel Kant (17241804).

Meeting of the Society of Friends (the Quakers).

CHAPTER 5

Pompeo Batoni, Peace and War (1776).

Elisabeth Louise Vige Le Brun, Peace Bringing Back Abundance (1780).

Gerard ter Borch, The Ratification of the Treaty of Mnster (1648).

Peter Paul Rubens, Minerva Protects Pax from Mars (c. 162930).

The Salon of Peace, Versailles.

Charles Le Brun, The King Governs by Himself, 1661 (1680s).

Stefano Torelli, Catherine the Great in the Guise of Minerva, Patroness of Art (1770).

Stefano Torelli, Allegory on the Victory of Catherine the Great over Turks and Tatars (1772).

Matvey Fedorovich Kazakov, Public Celebration that was Held on the Khodynka Field on 19 July 1775 (1775).

Anton von Maron, Portrait of Empress Maria Theresa as a Widow (1773).

Benjamin West, The Treaty of William Penn with the Indians (177172).

Jacques-Louis David, Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799).

Antoine Jean Gros, Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau (1807).

RONALD EDSFORTH

When people learn that I study and teach peace history, they often look puzzled and ask me, Does peace have a history? A Cultural History of Peace is an emphatically positive response to that question. Yes, peace has a history. The original scholarly essays collected in these six volumes clearly show that peace always has been an important human concern. More precisely, these essays demonstrate that what we recognize today as peace thinking and peace imagining, peace seeking and peace making, peace keeping and peace building have long recorded histories that stretch from antiquity to the twenty-first century. All of us who have contributed to A Cultural History of Peace believe that present and future generations should have the opportunity to recognize and understand the importance of this peace history.

Very few universities and colleges had faculty who taught and researched peace history before the end of the Cold War. Even today, most professors who do peace history moved into it from other specializations in History or other academic disciplines. Most contributors to A Cultural History of Peace are professional historians, but Anthropology, Sociology, Political Science, Journalism, Art History, Religion, and Classical Studies are also represented. These fifty-six contributors work on four continents in thirteen different countries. Their participation in this project tells us that peace history has earned a global recognition in academia that not so long ago was unimaginable. Their essays build upon prior scholarship, but they are also introducing new research and new interpretations. As a whole A Cultural History of Peace highlights our humanity, something that has been for too long overshadowed in history by the inhumanity of war and other forms of violent conflict. Pursuing answers to new and seldom asked questions, these collected essays expand our knowledge of when, how, and why people in the past pursued peace within their own societies and peaceable relations with people from other societies.

The South African novelist Nadine Gordimer wisely observes, The past is valid only in relation to whether the present recognises it. (2007: 7). In other words, what happened in the past is not necessarily history. History is made when scholars produce meaningful answers to the questions they ask about the past. The past cannot change, but history can and does change when scholars ask new questions, and when they use previously undiscovered or ignored evidence to develop new interpretations of the past. Evidence of what people said or did, or said they did, are basic materials out of which scholars shape answers to questions like Does peace have a history? Of course, to answer this particular question about the past, we must have in mind some definition of peace. Like most people we probably immediately think of peace as not war, a classic definition that describes peace in negative terms, as an absence of the type of violent conflicts that still loom so large popular histories and stories about the past. The American psychologist and peace activist William James succinctly summed up this common way of framing of the past, simply stating, History is a bath of blood. (1910: 1).

James description of history still plays well in a world that during the last century experienced the massive casualties and devastation of two world wars, genocides, and numerous civil wars, as well the fears created by transnational terrorism and still-threatening nuclear arsenals. And significantly, a bath of blood framing of continues to shape the priorities of most mainstream reporting of the news from around the worldif it bleeds it leadswhen, in fact, most people today live in zones of peace where their lives are not threatened by violent political conflict. A human beings chances of dying in war have been historically low in this century, and in striking contrast to the peaks of worldwide violence reached during the global conflicts of the twentieth century. (https://ourworldindata.org/war-and-peace) Yet so accustomed are we with framing history and the present as a bath of blood, most of us have difficulty comprehending these facts. Steven Pinker recently noted this problem in the preface to The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

Next page