This edition is published by Arcole Publishing www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books arcolepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1946 under the same title.

Arcole Publishing 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

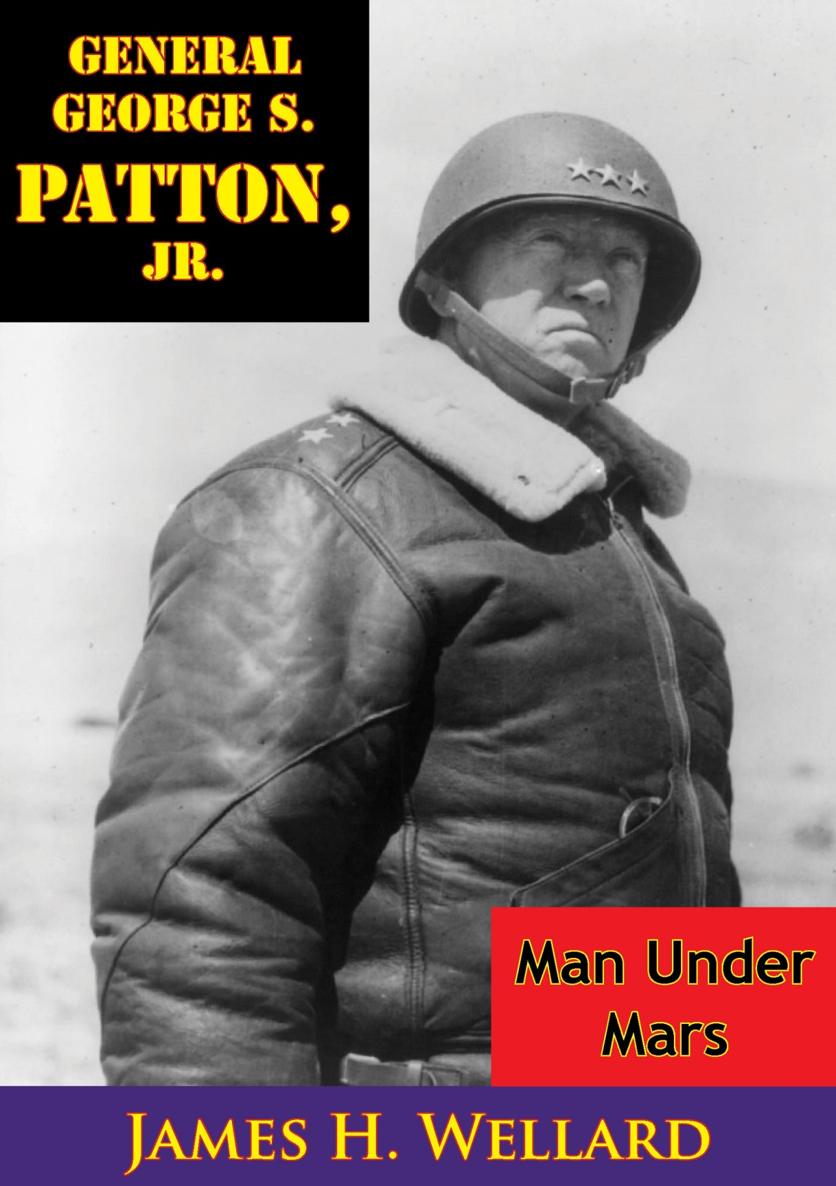

GENERAL GEORGE S. PATTON, JR.:

MAN UNDER MARS

BY

JAMES WELLARD

With Illustrations and Maps

PREFACE

This book is not an official biography of General George Smith Patton, Jr.; it is an interpretative study of an American who typifies in his career and personality a phase of history which has just ended with the last of what we may come to know as the Gunpowder Wars.

So far, Patton has been written about almost exclusively under the title of Old Blood and Guts, though no one associated with him or his armies ordinarily calls him by that name. The impression given by newspaper and magazine accounts is of a brilliant and impetuous general who makes war as exciting and colorful a spectacle as an epic in glorious technicolor.

Whatever Patton did, he seems to have had a label slapped on him. The labels are many, including among the more complimentary, Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, The Man from Mars, The Green Hornet, Iron Pants, and, of course, Old Blood and Guts. After the slapping incident in Sicily, he was known as the man 50,000 G.I.s were waiting to shoot, After the Third Armys victories in Europe, he was re-labelled Hero. Before long he can, in the nature of things, expect to be called Fascist and Warmonger.

Who, then, is this Patton who is booed one day and applauded the next by a hundred million of his fellow countrymen? In this book I have tried to tell, by relating the whole story of the man, his exploits, and his beliefs. I have tried to show that Patton is not a man covered over with many contradictory labels, but a soldier whose life has been devoted to a single idea which he has elevated into a faith. That idea, or faith, is a passionate love of war, which becomes, in Patton, a martyrs urge to die on the battlefield.

It is hard for civilians in a modern democratic society to understand this self-sacrificial love of war, for the warrior class which held such ideas is now almost extinct. But war is what Patton believes in; and it is this belief which explains why he was once called Hero, why he pommeled a sick soldier, why he raced across Europe, why he attacked the Siegfried Line in the depth of winter, why he crossed the Rhine without firing a shot, why he came home a Conqueror, why he told a Sunday-school class there would always be wars, and why he showed covert sympathy with Nazis in Occupied Germany.

If Patton was merely the exponent of the gospel of expert killing, he would be a more fitting subject for a military historian than for me. But his personality and ideas fell with tremendous impact on millions of Americans who fought in the last of the Gunpowder Wars; and I felt that in telling his story I could tell, in part, their story, too.

So I have attempted to describe Patton as I saw him against the background of great events, when I was serving as a war correspondent with his armies in Tunisia, Sicily, and Europe, from November, 1942, to May, 1945. What I saw and experienced helped me to understand not only Patton, but also the men who fought with him, and the war they fought, and the significance of that war to him and to them. Because I was a civilian, I saw many aspects of war which the professional soldier either does not notice or disregards; and I saw especially that while war has its sad splendor which Patton has glorified into a creed, it has a physical and spiritual ugliness which transcends even the beauty of brave men doing brave deeds.

And so when I came to examine the life and times of Patton, I tried to find in the circumstances of his origin and environment an explanation for the prayer he addresses to a Deity he calls God of Battle, a prayer which says: To slay, God make us wise. My inquiries took me as far back as another Patton who lived a hundred years ago, Brigadier-General George Smith Patton, who died a heros death on the field of battle at Winchester, September 9, 1864.

This, then, is where the book begins; and it ends almost a century later, June, 1945.

In writing this first book-length biography of Patton, I had a great deal of material based on his exploits as commander of our European armies, but little or nothing on the previous phases of his life. The short newspaper and magazine accounts which have appeared in the last three years were full of picturesque episodes and quotations; but they all seemed, to me at least, rather hearty and hasty attempts to justify a successful general to a dubious public. I found, for instance, a whole series of oft-repeated stories which had a vaguely apocryphal sound. There was the story of the twenty-six polo ponies which Patton was reputed to have taken to his first camp in Texas, after he graduated as a second lieutenant from West Point, I mentioned this story to Mrs. Beatrice Patton, the generals wife, and received an indignant denial: We never had twenty-six ponies.

I realized, then, in order to get an accurate account of Pattons early life, I would have to consult people rather than records. I, therefore, applied to Mrs. Patton, who graciously received me, and gave me the data I needed, even though her experiences with interviewers had not been happy ones; for the information she gave them, she said, was often distorted or misused. Nonetheless, she was kind enough to go over the part of the manuscript I had finished, correcting certain errors of fact, and to give me material for the earlier chapters.

I wish to thank Mrs. Patton for her invaluable help, at the same time pointing out that she is in no way responsible for any of the views about her husband which I have put forward; but, on the contrary, she is in strong disagreement with many of the conclusions I have drawn. But I believe my facts are accurate, and the twenty-six polo ponies, together with a number of other tall tales, are, thanks to her guidance, now struck from the record.

I also had the opportunity of talking with men who knew Patton before and during the First World War, and from them I obtained certain information which is incorporated into this book. All of it is not favorable to Patton; but I was not writing either a panegyric or an obituary; only a factual account with a personal interpretation of those facts. Admirers of the General may disagree with my interpretation on the grounds that I have overemphasized the less favorable aspects of his character. His friends at West Point will hotly dispute the statement that he was unpopular at the Academy, or that he was called a quilloid, though this information was forthcoming from a fellow cadet of the same class as Patton. Others may object to my account of Pattons role in the Mexican and First World Wars; but here again I have drawn my own conclusions from the accounts of his contemporaries.