This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 2006 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

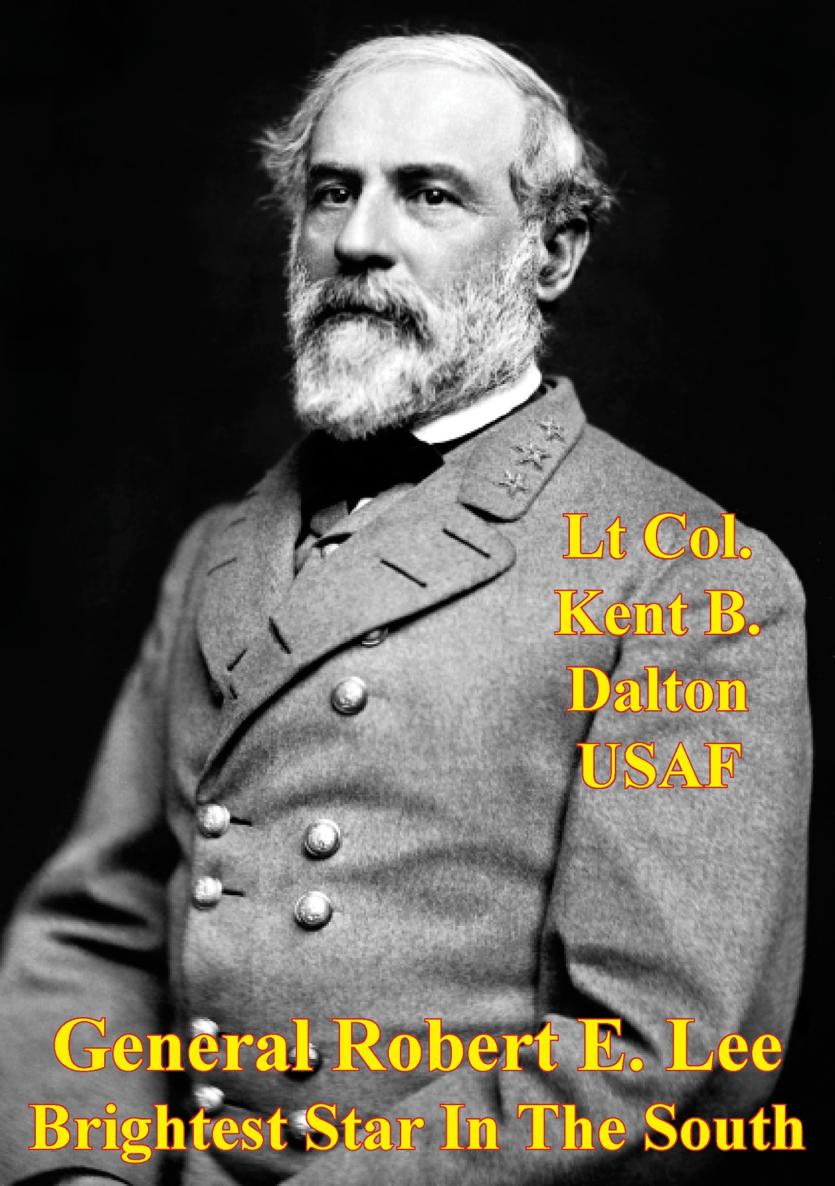

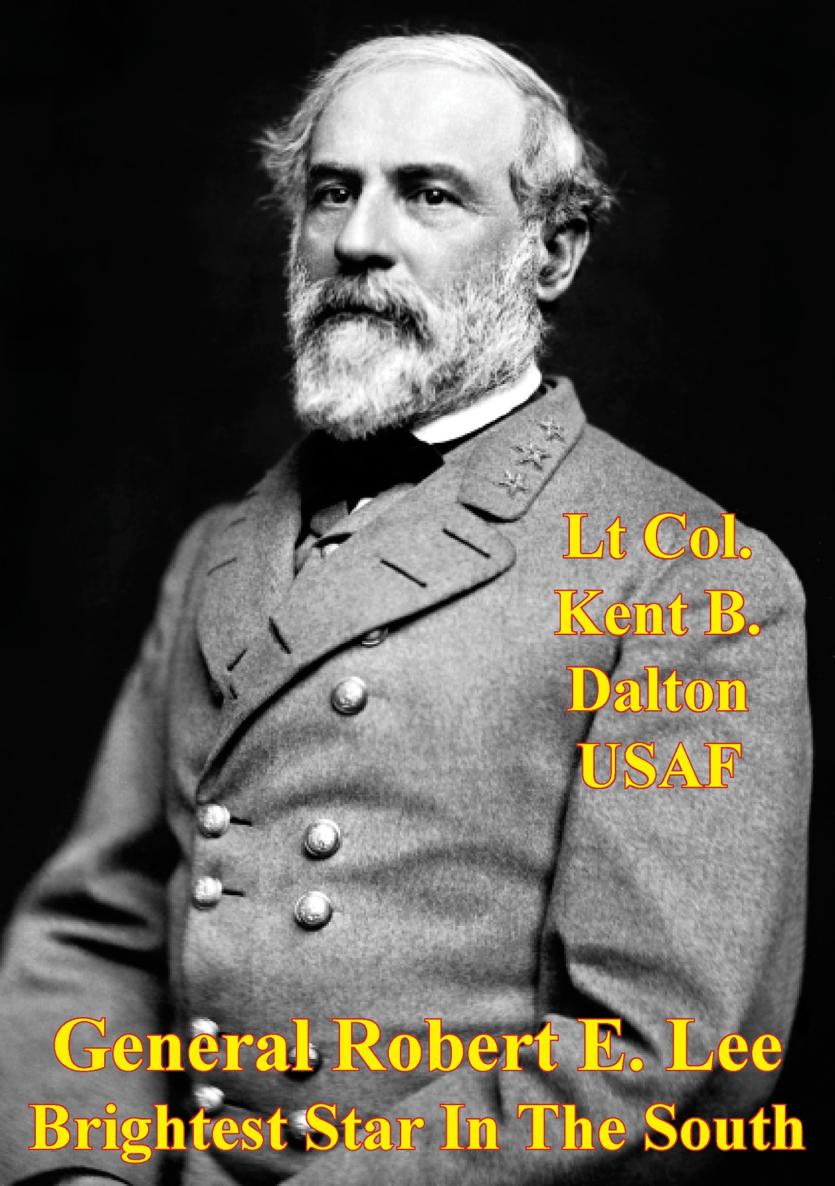

General Robert E. Lee -- Brightest Star in the South

by

Kent B. Dalton Lt Col., USAF

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

History is often overlooked for its value in terms of lessons learned. By examining General Robert E. Lees distinctive application of operational art and leadership as the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, we can discern many lessons which are still pertinent to our commanders at the operational level today. From his selection of Lieutenant General Thomas Stonewall Jackson as one of his corps commanders during his reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia, his methods to build morale to his strategy and his balancing of Space, Time and Force there are many lessons to be learned

INTRODUCTION

History provides many examples of brilliant combat leaders who have led their forces to victory in the field. Hannibal, Lord Nelson, General George S. Patton Jr., and General Norman Schwarzkopf are only a few. There has been a great deal written about battles, campaigns and wars fought in the past. We enjoy these writings for their historical value but oftentimes these events are overlooked for the value of the lessons we can learn from the action and inaction of the participants. Even when lessons are learned from these past engagements, they are often forgotten or the events themselves are not even examined. For example, during the early 1960s, when Americas involvement in Vietnam was on the rise, one American four-star general remarked that there was not much to learn from the French since they had not won a war since Napoleon had been in power. {1} Although some of these leaders lived long ago, and the engagements they fought in took place several years in the past, in some cases, hundreds or even thousands of years ago, they still hold many pertinent lessons for our 21st century operational commanders.

One such leader from who we can learn is General Robert E. Lee, Commanding General of the Army of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War. During the Civil War, Lees command of operational art and leadership was exemplary and can serve as a model to emulate. More importantly, there are pertinent lessons our 21 st century military leaders can learn from Lees distinctive application of operational art and leadership. In this paper, I will examine Lees relationship with Lieutenant General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, and why it mattered to General Lee and the Confederate cause, how General Lee raised morale, his strategy during the war, and how he seemingly bent the factors of space, time and force at the battle of Chancellorsville to engineer a victory against a much larger Union army. I will also touch on the lessons learned from each area covered and their implications for our operational level commanders of the 21 st century. Before delving into these areas, a short background on General Lee is appropriate.

BACKGROUND

General Robert E. Lee was the quintessential operational leader. He spent nearly his entire life in preparation for the time when he would command at the operational level. During the American Civil War he would prove time and again that he was a true master of the operational art.

Robert E. Lee was born January 19, 1807 at Stratford, his ancestral family home, in Northern Virginia. He was the fourth child of Ann Hill Carter and Henry Light-Horse Harry Lee, Revolutionary War hero and governor of Virginia. Completing his studies at Alexandria Academy, where he excelled in Latin and mathematics, he received an appointment for the United States Military Academy at West Point. Graduating second in his class in 1829, Lee was assigned to the armys elite Corps of Engineers. After graduating from West Point, General Lee continued a robust self-study program in military matters, paying particular attention to the writings of Baron Antoine Henri Jomini. {2} In 1831, he married Mary Randolph Custis, daughter of George Washington Parke Custis, step-grandson of George Washington, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis. Over the next 15 years, Lee spent most of his time in the army doing engineering work on coastal fortifications and re-directing rivers for navigation. {3}

In 1847, Lee reported to General Winfield Scott who was preparing to attack Vera Cruz in Mexico. Lee assisted in the planning of this successful operation, which was his first time in combat. It was under Scotts tutelage that Lee first learned how a smaller but better-trained force should deal with a numerically superior force in a stronger position.

Lee participated in more battles, leading troops and conducting critical engineering and scouting duties. During his time in Mexico, Lee learned many valuable lessons. First, he learned that a numerically inferior foe could engage and defeat a larger force, even if that force was on the defensive. To make this happen, four things were required: all information about the adversary and terrain had to be collected and analyzed, the commander of the smaller force had to be willing to take risks, had to make a decision and act on that decision, even in the face of criticism from subordinates, and had to seize the initiative. Lee gained the ability to read terrain over and above that required of a normal engineer and also came to understand the value of maneuver and the advantages of attacking an opponents flank. {4} All of these lessons were to serve him well in the future.

Lee served as the superintendent at West Point from 1852-1855, where he conducted an extensive study of the campaigns of Napoleon. His interface with faculty and visitors served to build on his already considerable military knowledge. After his stint at West Point, Lee was transferred to the cavalry as second-in-command of a regiment.

In October 1857, his wifes father died and he went back to Arlington, Virginia to handle affairs surrounding this event. {5} Lee was still in Virginia in 1861, when southern states started seceding. On April 18, 1861 Lee learned of Virginias secession. He was offered command of all Union forces but he turned down the opportunity because of the duty he felt towards Virginia. On April 23, 1861, he accepted the post of commander in chief of Virginias military forces. Three weeks later he became a brigadier general in the Confederate army. {6} He had some unsuccessful campaigning in western Virginia, spent time in the Carolinas preparing coastal defenses and was appointed military advisor to the Souths president, Jefferson Davis. {7} On June 2, 1862 he became the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, replacing General Joseph Johnston who had been wounded in battle. {8} One of the first things Lee would do was to reorganize his personnel.