INTRODUCTION

At the top of the world, an invisible circle stretches several hundred miles around the North Pole. Humans have lived in this region, called the Arctic Circle, for tens of thousands of years. They learned to survive in its cold and snowy climate by hunting and fishing. But for some who have dared to explore the region, ice and cold have proved deadly. On some Arctic expeditions, only a few people survived journeys that doomed their companions.

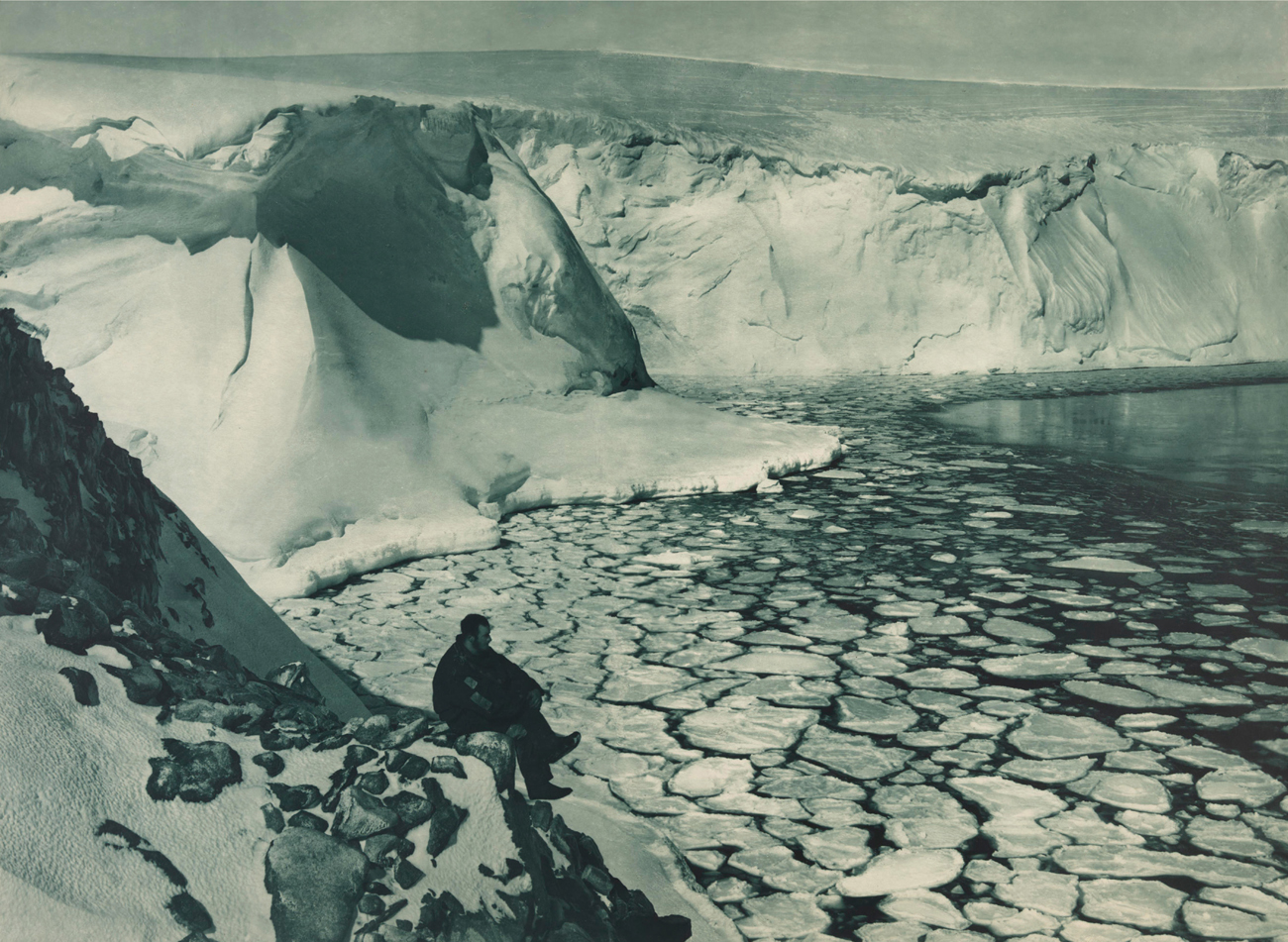

On the opposite end of the globe, an even colder land surrounds the South Pole. Antarctica is one of Earths seven continents, and its climate is the harshest on the planet. Blizzard winds there can reach 200 miles (322 kilometers) per hour. Temperatures often plummet to minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 73 degrees Celsius) or more. Ice sheets in Antarctica can be more than 1 mile (1.6 km) thick. Unlike the Arctic, no one settled in Antarctica until 1898, when the first scientists set up a base to study the weather and wildlife there. But even before then, brave explorers made the difficult journey to Antarctica. Some wanted to reach the South Pole. Others sought to map the geography. Even today, some people attempt to ski across the remote southern continent. They love the adventure of pushing themselves to withstand the extreme cold and isolation.

Whether theyre explorers, scientists, or sailors, several people have survived the harsh conditions of the polar regions. In the stories ahead, youll meet people who could have died from starvation or the bitter cold during missions that went wrong. But in most cases, their incredible courage and skill, along with some luck, helped them survive the most extreme locations on Earth.

In the early 1900s, few people had the strength and courage to explore Earths harsh polar regions.

AND THEN THERE WAS ONE

Douglas Mawson

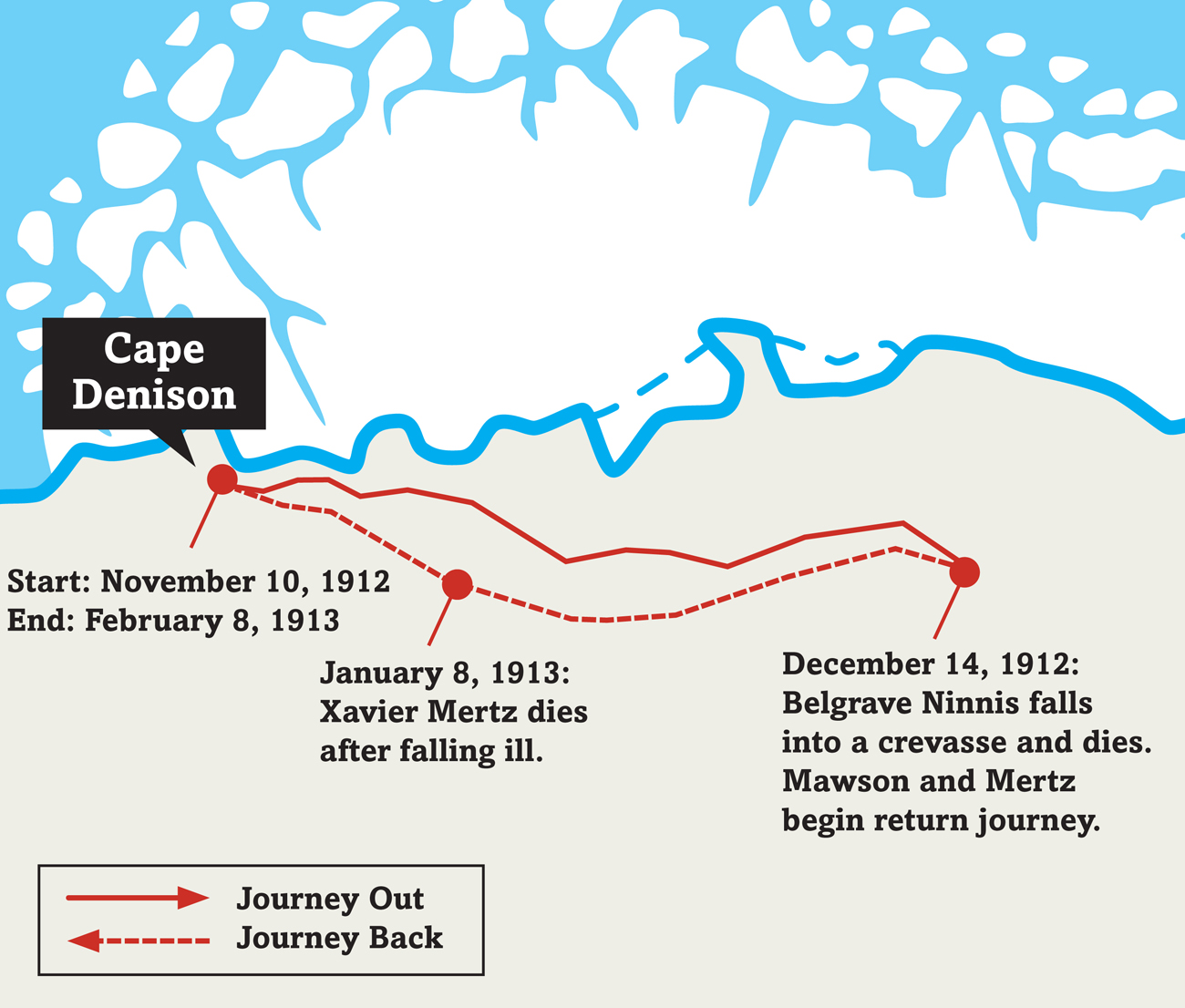

With 16 Douglas Mawson was ready. On November 10, 1912, he set off to explore the northern coast of Antarctica. No human had ever gone there before, and Mawson wanted to map the area and collect mineral samples.

Joining him on the Ernest Shackleton, who had hoped to become the first person to reach the South Pole. After that first trip, Mawson decided he wanted to return to Antarctica to focus more on science.

As Mawson and his partners set off with their dogs, they hoped to reach a point about 350 miles (563 km) southeast of the expeditions main base at Cape Denison. They had to get there and back by January 15, 1913. That day, the Aurora would return to pick up the expedition members and bring them back to Australia. The men had just enough food to last for the two months they would be on the ice. And if they missed the ship, they would have to wait another eight months for it to return in the spring. South of the equator, the seasons are reversed, so spring begins in September.

A few days out from the main base, even as summer approached, Mawsons team got a taste of Antarcticas extreme weather. A dogs plunged into one. Luckily, the men were able to pull them back to safety.

Did You Know?

Douglas Mawson was just one of several explorers traveling across Antarctica in 1911 and 1912. When Mawson left Australia in December 1911, Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott were each attempting to reach the South Pole. Mawson had met Scott previously in 1910. The explorer had asked Mawson to join his expedition. Mawson said no, since Scott wasnt interested in exploring Antarcticas northern coast. Mawson later learned that Scott had lost to Amundsen in the race to the South Pole. Scott and the rest of his five-man team died on their return journey.

Roald Amundsen and his team of sled dogs at the South Pole on December 14, 1911

A Dangerous Crevasse

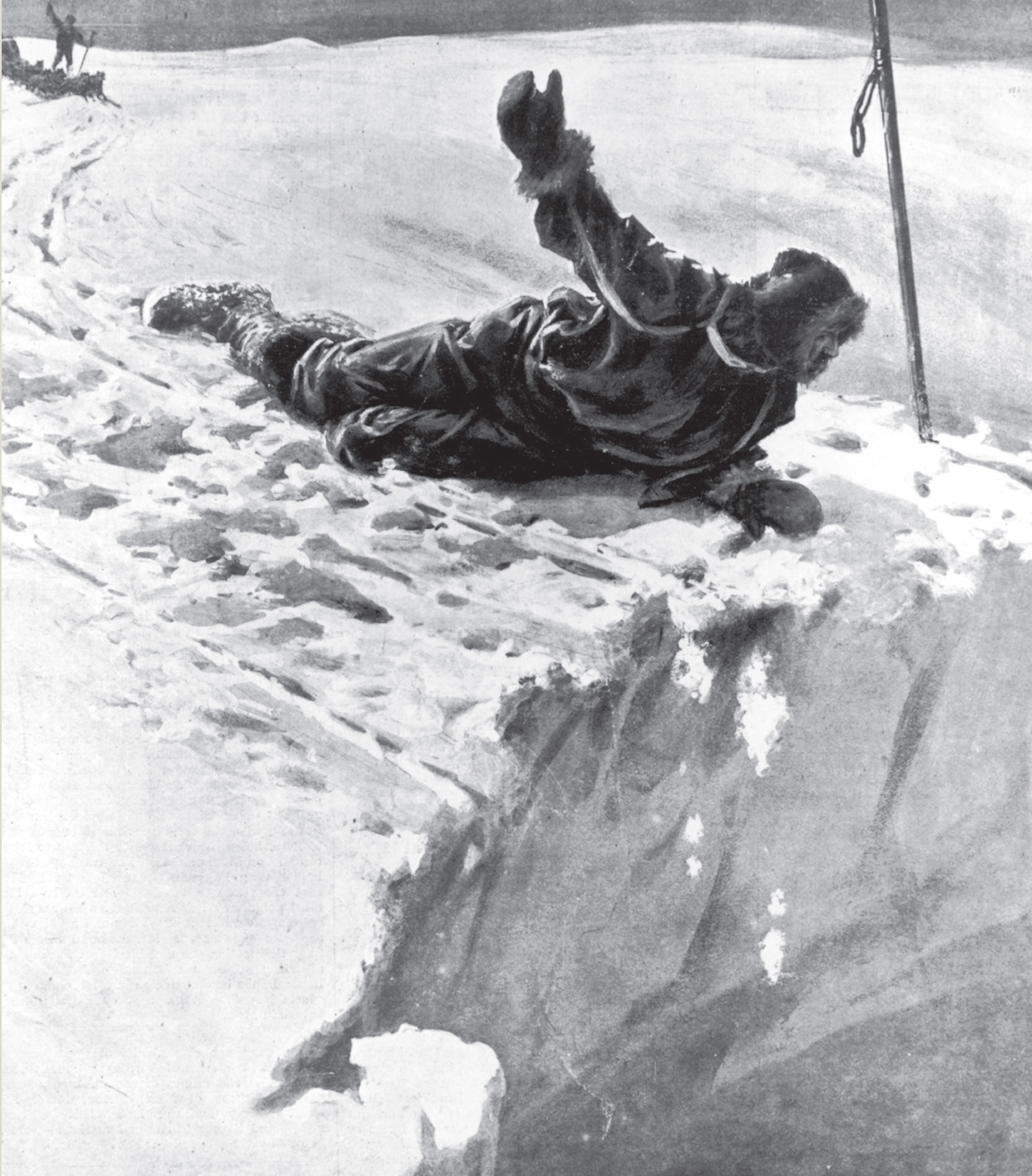

The danger of falling into crevasses and losing dogs only seemed to grow as the team went on. Ninnis started to fall into a crevasse but was able to pull himself out. One sledge nearly fell into another crevasse, but its runners caught in the ice before it went too far. However, the team lost several dogs. One wandered off and was never seen again. The team also killed some dogs that couldnt keep up the pace. Their meat became food for the remaining dogs.

Despite the setbacks, after about a month, the team had covered almost 300 miles (483 km). On December 14, the men woke to sun and relatively warm temperatures, about 21 F (-6 C). That day Mertz was traveling on skis when he signaled that he was crossing a crevasse. Mawson passed a warning back to Ninnis, who was guiding the last sledge. Mawson then continued on. But then he saw that Mertz had stopped and was looking behind him. When Mawson turned to look, Ninnis and his dogs had vanished.

Mawson and Mertz went back to the crevasse. A snow bridge had given way, revealing a gap about 11 feet (3.4 meters) wide. When Mawson looked down, he could see one of the dogs on a shelf of ice, some 150 feet (46 m) below. But there was no sign of Ninnis. Mawson and Mertz shouted down into the gap, but they didnt get a response. Ninnis was dead.

The team didnt just lose a trusted companion. The sledge Ninnis was steering had carried most of the teams food and important equipment. Mawson figured they had enough food left to last about 10 days. That night the men boiled their empty food bags to get the last crumbs out of them. They fed leather to the remaining dogs.

The next day and only luck would decide if they won.

The group suffered a terrible blow when Ninniss sledge fell into a deep crevasse. Along with Ninnis, the team lost several dogs, the tent, clothing, and most of the food.

Growing Weaker

Day after day, the two men traveled west. Some days were clear. But other days the snow whipped around them. They ate only the smallest amounts of food, hoping to make what they had last as long as possible. As they grew weaker and the number of dogs fell to three, they threw away what they could to lighten the load on the sledge. More than a week after Ninniss death, they still hadnt reached the halfway point back to the base.

On December 28, Mawson and Mertz killed the last dog. But its meat lasted only for a few days. As the New Year began, Mertz showed signs of failing health. His energy faded, his fingers were frostbitten, and patches of skin fell off his legs. He stopped eating solid food, getting down only some powdered milk mixed with water.

By January 7, Mertzs poor health slowed the men down to only about 1 mile (1.6 km) each day. At this rate, they would never reach the base by January 15. Still, Mawson knew he couldnt leave Mertz behind. That day, however, Mertz had what Mawson called fits. He was too weak to even leave his sleeping bag to relieve himself. Early on the morning of January 8, Mertz died. Mawson would have to cross the remaining frozen miles alone.