Published in 2016 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2016 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J. E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Zoe Lowery: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Introduction and supplementary material by Norman Graubart

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The American Revolution: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness/edited by Zoe Lowery.First edition.

pages cm.(The age of revolution)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6804-8022-1 (eBook)

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Juvenile literature. I. Lowery, Zoe.

E208.A435 2015

973.3dc23

2014041869

Photo credits: Cover, p. 1 Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock.com; p. vii DEA Picture Library/Getty Images; p. 4 Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum; photograph, J.R. Freeman & Co. Ltd.; pp. 2021, 40, 69 North Wind Picture Archives; p. 22 Heritage Images/Hulton Fine Art Collection/Getty Images; p. 25 Danita Delimont/Gallo Images/Getty Images; p. 29 MPI/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 31 1903 John H. Daniels & Son, Boston/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (pga-00995); pp. 35, 109 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 46 National Archives, Washington, D.C.; pp. 5051, 129 Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 56 US Capitol Collection, Washington, D.C., USA/Photo Boltin Picture Library/Bridgeman Images; pp. 72, 81 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; pp. 78, 116, 133 SuperStock; p. 83 Art Images/Getty Images; p. 85 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Digital file number: cp 3g06222); p. 93 Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA, USA/Bridgeman Images; p. 95 World History Archive/SuperStock; p. 97 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts, USA/Bequest of Winslow Warren/Bridgeman Images; p. 115 BackyardProduction/iStock/Thinkstock; p. 136 Photos.com/Thinkstock.

CONTENTS

I have never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries, would take place at one time or other

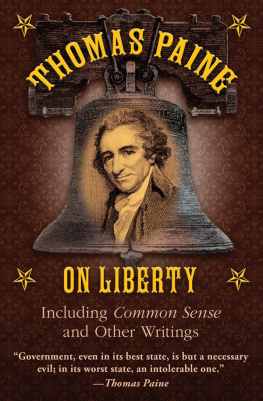

Thomas Paine, from Common Sense

W e often think of the American Revolution as being predestined, or bound to happen. But was it indeed inevitable? Thomas Paine, an English pamphleteer who lived most of his life in the 13 colonies, seemed to think so. To him, England was a nation of backwardness. He believed that the system of monarchy made it very easy for the population to understand where all of their problems came from (the king), but it also made them unable to fix their problems in a rational manner through government. As the colonists became more self-sufficient, they began to lose their affection with this system, just as Paine had. Those who would follow this line of reasoning and support independence were called patriots.

But not all colonists were patriots. Loyalists believed, even well into the Revolutionary War, that the colonies should remain with England. There were many reasons for this. Its important to remember that, before the Revolution, the colonists were subjects of the British Empire. This meant that they were not citizens of a republic but in fact owed their very existence and their human rights to the king and queen of England. Most of these subjects shared their church, their language, and their traditions with England. Those subjects who cared about these connections more than taxes were likely to become loyalists. To be a patriot was to have faith and hope that breaking these historical connections would be a reasonable price to pay for establishing a republic.

THOMAS PAINE (17371809) WAS A POLITICAL WRITER WHOSE PAPERS, SUCH AS COMMON SENSE, SPURRED AMERICANS INTO ACTION AND, ULTIMATELY, REVOLUTION.

But were the forces of loyalism and patriotism bound to fight each other in the end? Could there have been a compromise? This is where the preceding Paine quotation becomes revealing. It was not just the colonists or the patriots who saw the Revolution coming. Paine makes no such distinctions in his statement. According to him, all men both in England and America believe that a separation [will] take place at one time or other. This statement alone was neither an endorsement nor repudiation of the Revolution (although Paine was perhaps the most ardent patriot writer) but an observation about both the English and American political environments of the time. In other words, whether you wanted revolution or you wanted to keep the relationship with Britain, the news of the day forced you to have an opinion. And the news was revolution.

Whether or not the Revolution itself was inevitable, its certainly true that the Revolution could have failed. This resource recounts a great deal of military history, beginning with the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1776 and ending with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. It also covers the young, untested general named George Washington and the intimidating British figure of Lord Cornwallis. While it might be something of a clich to say that the American Revolution was a war waged against all odds, this is in fact the case. Had France not offered its help, had the British been more strategic militarily, and had the colonists been less sure of their cause, the Revolution could have been easily squashed. While the colonists knew their territory better than the British, they were largely unskilled and lacked the order and sophistication of the British army. Furthermore, this resource will discuss how the British failed to win the war by failing to devise a strategy that could outsmart and outkill the driven revolutionaries.

To be sure, the American Revolution was not a sudden earthquake or volcanic eruption. It had its causes and could perhaps have had several different outcomes. But the conflict over something as mundane as taxes put several social forces up against each other in plain view. Now, the idea of self-government was put squarely in opposition to the concept of autocratic, hereditary monarchy. The idea of a state church withered in a vast network of diverse colonial states and communities, where religious revivals and new branches of Christianity were thriving against the official backdrop of a distant, hierarchical Anglican Church.