A Chance in Hell

A Chance

in Hell

THE MEN WHO TRIUMPHED

OVER IRAQS DEADLIEST CITY

AND TURNED THE TIDE OF WAR

JIM MICHAELS

ST. MARTINS PRESS

New York

A CHANCE IN HELL . Copyright 2010 by Jim Michaels.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

For information, address St. Martins Press,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

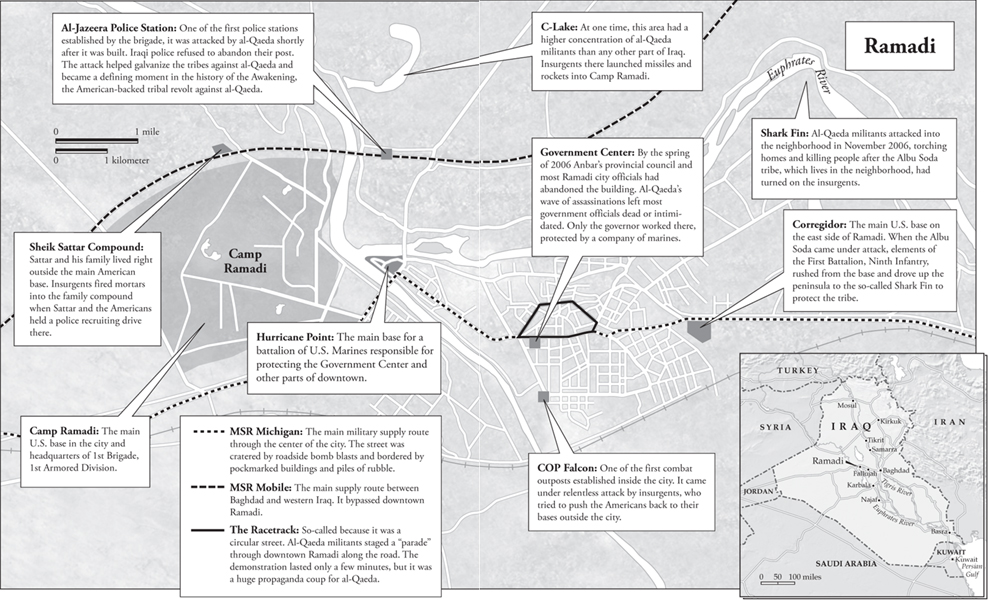

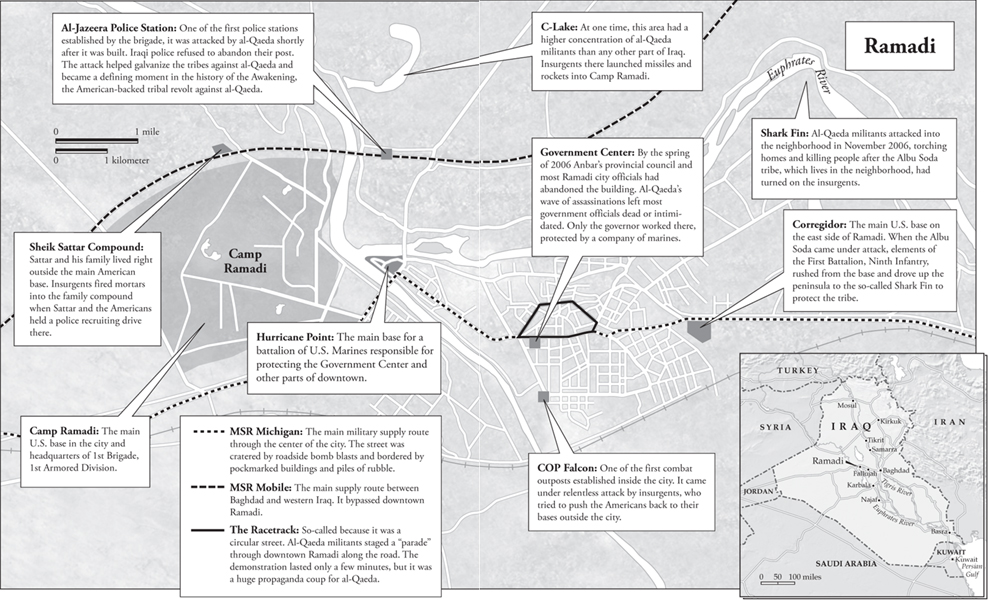

Map by Paul J. Pugliese

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Michaels, Jim.

A chance in Hell : the men who triumphed over Iraqs deadliest city and turned the tide of war / Jim Michaels.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-312-58746-8

1. Iraq War, 2003CampaignsIraqRamadi. 2. United States. Army. Armored Division, 1st. I. Title.

DS79.766.R36M527 2010

956.7044'342dc22

2010002173

First Edition: June 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the sons of Anbar, Iraqi and American

CONTENTS

A Chance in Hell

INTRODUCTION

The idea for this book originated during a meeting with a State Department source in the lobby of the Al-Rashid Hotel in Baghdad in the summer of 2006. Sipping thick Turkish coffee amid the the hotels faded carpets and Saddam-era faux chandeliers, my source talked about strange developments in Ramadi, a provincial capital about seventy miles west of Baghdad. An army brigade commander there was making peace with tribes in the heart of insurgent territory.

The source, who made frequent trips to Anbar and had been in the country for years, wasnt entirely approving of developments there. The brigade commander, Col. Sean MacFarland, was dealing with a minor tribe. His higher command, the Marine Expeditionary Force, was attempting to work with the major sheiks, most of whom had decamped to Amman, Jordan. MacFarlands strategy was showing promise in Ramadi, but threatened to upset the larger strategy in the Sunni province. It wasnt clear where all this was heading.

The story was intriguing, though I was skeptical it had the broad implications necessary for a cover story in USA Today. At best it was a bright spot amid a war that was going poorly. It was hard to be optimistic about Iraq in 2006. At best, Ramadi would make an interesting color story; shades of T. E. Lawrence. There was something romantic about desert tribes. I asked a few questions, flipped my notebook shut, and walked from the lobbys chilled air into the Baghdad summer. I was finishing up a reporting trip and it would be several months before I was back in Iraq. I figured the story could wait.

I was wrong. Within months, Ramadi had gone from an insurgent safe haven to a model of stability. The turnaround was largely ignored by the media at the time and was overshadowed by unrelenting bad news elsewhere in Iraq and policy gridlock in Washington.

What happened? I got a chance to find out in the spring of 2007 when I heard that an army team was going to Germany to gather lessons learned from MacFarlands First Brigade, First Armored Division, which had just returned from Ramadi to its base in Friedberg, Germany. Col. Steve Mains, director of the Center for Army Lessons Learned, without hesitation allowed me to accompany the team to Germany. I spent several days interviewing commanders, staff officers, and noncommissioned officers in the bucolic setting of the German countryside.

It was hard to escape the conclusion that the success in Ramadi was more about the artnot the scienceof war. It was a story about leadership and how the decisions of individuals can change the tide of history.

The idea of a peaceful Ramadi seemed far-fetched when the brigade first arrived. The city looked like Stalingrad under seige. There was no other way to describe it. Americans were lobbing rockets into the center of the city on a regular basis. Anbar Province was a sideshow. The real effort was in Baghdad. Other units and commanders came and went in Ramadi. MacFarland saw something many others missed. He didnt fall back on regulations and policy guidance. He was given latitude and he took every inch of it. When his higher command wanted to put the brakes on his initiative, he pushed back.

MacFarland was only part of the equation. The other half of this remarkable story was Abdul Sattar Bezia al-Rishawi. Sheik Sattar was easy to overlook. He was a minor sheik and the head of a small tribe. He carried around a six-shooter and liked whiskey. A cautious military commander would keep the likes of Sattar at a distance.

MacFarland embraced the sheik. Sattar returned the embrace. Its hard to overestimate how crucialand courageousthat decision was for both men. When the war looked hopeless these two men helped changed the course of history. That is not to take away from anything that has happened before or since. But this story reminds us all that wars are won and lost by men and women and the decisions they make.

It is wrong to think of this as an American initiative. It was a tribal revolt against al-Qaeda. But MacFarland made the very risky decision to support it. History would have been different had he made another call.

What happened in Ramadi in 2006 is not well understood.

Even as it became clear that Ramadi was improving dramatically in late 2006, Baghdad and other parts of Iraq continued to slide downhill. The policy for Iraq in Washington was in disarray. In January 2007 the White House announced a new strategy backed by temporary reinforcements of 30,000 surge forces that would be deployed to Iraq. Most of the troops were headed toward the capital. The developments in Ramadi would soon be overshadowed by a massive flow of American troops into Iraq under the new plan.

The story of the surge and MacFarlands experience in Ramadi would briefly surface as an issue in the 2008 presidential campaign. Senator John McCain had tied his political fortunes to the White Houses surge strategy. McCains critics said the developments in Ramadi in 2006 proved that progress in Iraq had started before the surge, suggesting the new method was irrelevant at best.

This book will likely reignite the debate. That would be too bad. The argument missed the point, as political squabbles often do. MacFarlands Ready First Brigade succeeded because they were using the tactics of the surgethough officially the strategy had not been launched yet. Gen. David Petraeus, who was appointed to lead the new U.S. effort in Iraq, institutionalized those tactics across Iraq, averting disaster and putting the war on a path toward victory.

There had been other successful efforts at reconciliation, dating back to 2003 when Petraeus was a division commander and was reaching out to former Baathists. In 2005, Marine Lt. Col. Dale Alford formed an alliance with the tribes and pushed al-Qaeda out of al-Qaim, a small city near the border of Syria. An army brigade in Tal Afar, in northern Iraq, built a model of stability by forming alliances with local leaders. But MacFarlands alliance with Sheik Sattar defeated al-Qaeda in a strategically important city. This model of cooperation to end al-Qaedas presence in Iraq was supported by Petraeus and soon there were awakenings across the country.