Contents

Guide

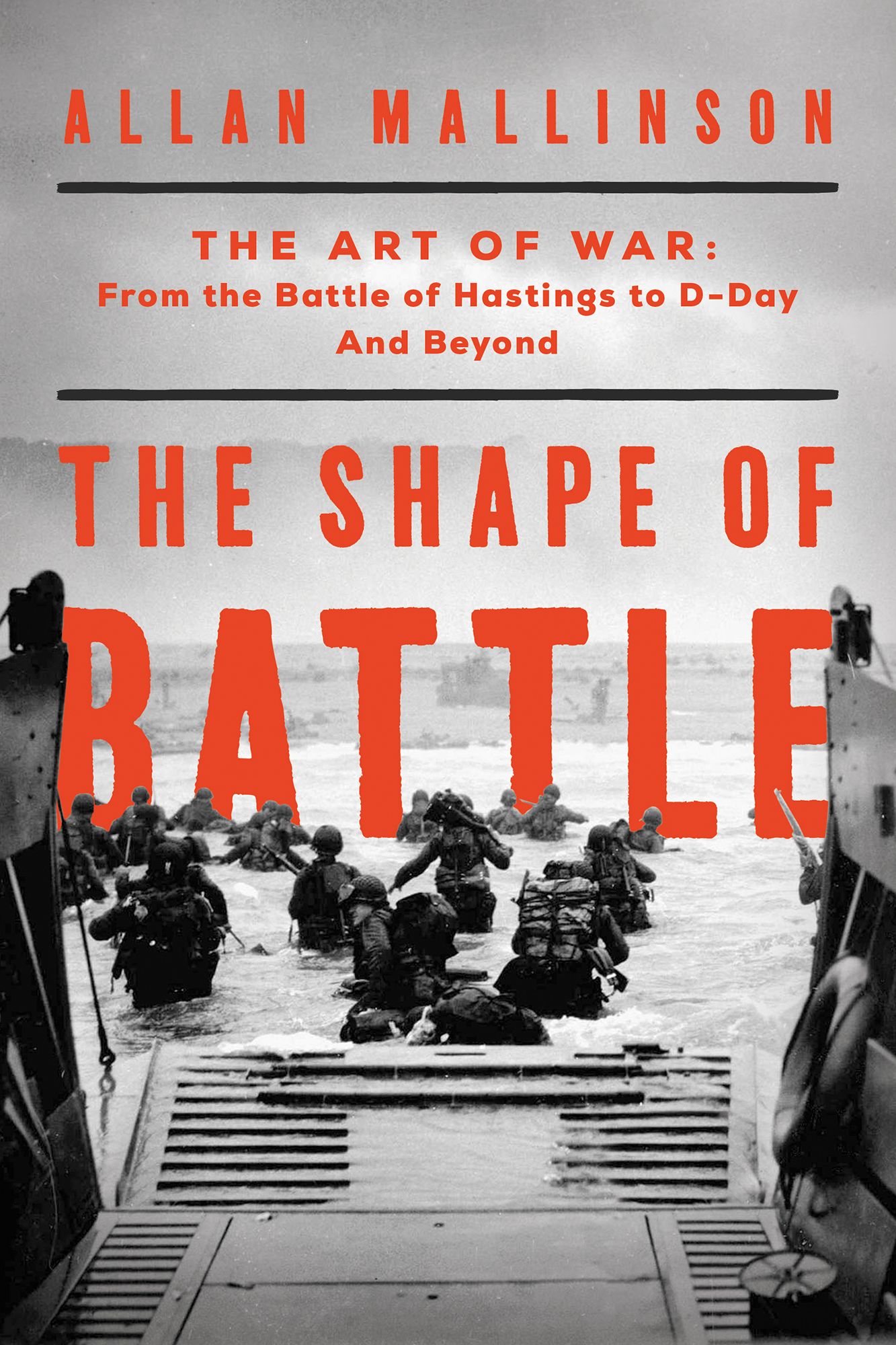

Allan Mallinson

The Art of War: From the Battle of Hastings to D-Day And Beyond

The Shape of Battle

Also by Allan Mallinson

LIGHT DRAGOONS: THE MAKING OF A REGIMENT

THE MAKING OF THE BRITISH ARMY

1914: FIGHT THE GOOD FIGHT BRITAIN, THE ARMY AND THE COMING OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR

TOO IMPORTANT FOR THE GENERALS: HOW BRITAIN NEARLY LOST THE FIRST WORLD WAR

FIGHT TO THE FINISH: THE FIRST WORLD WAR MONTH BY MONTH

The Matthew Hervey series

A CLOSE RUN THING

THE NIZAMS DAUGHTERS

A REGIMENTAL AFFAIR

A CALL TO ARMS

THE SABRES EDGE

RUMOURS OF WAR

AN ACT OF COURAGE

COMPANY OF SPEARS

MAN OF WAR

WARRIOR

ON HIS MAJESTYS SERVICE

WORDS OF COMMAND

THE PASSAGE TO INDIA

THE TIGRESS OF MYSORE

www.hervey.info

www.AllanMallinsonBooks.com

THE SHAPE OF BATTLE

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2022 by Allan Mallinson

First Pegasus Books cloth edition August 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-63936-193-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63936-194-6

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

Jacket credit: Faceout Studio

Art credit: Bridgeman + Shutterstock

The events of all wars are obscure.

History is only roughly right at best.

John Masefield, Gallipoli

The history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.

The Duke of Wellington

Battles are won primarily in the hearts of men.

Montgomery of Alamein

LIST OF MAPS

Part One Hastings

Part Two Towton

Part Three Waterloo

Part Four Sword Beach

Part Five Imjin River

Part Six Helmand: Operation Panthers Claw

PREFACE

The Shape of Battle isnt meant to be a coda to Clausewitz (On War) or a companion to Keegan (The Face of Battle), but is rather a study of why some battles were fought as they were, and as battles to one degree or another will always be fought.

No one battle is quite like any other in its shape and course. Each takes place in a different context the war, the campaign, the weapons, the people. Nevertheless, battles across the centuries, and the continents, have much in common, whether fought with sticks and stones or advanced technology. War is, after all, an intensely human activity; human nature doesnt change, and men are no more intelligent now than their predecessors of a thousand years ago.

Trying to seek the present, or the future, in the past is perilous, not least in using examples from history to confirm ones own preconceptions and prejudices. The past has first to be engaged with on its own terms. Yet if battles didnt have anything in common, why would professional soldiers study them? What other than diversion would they find useful in old battlefields? That most assiduous student of the soldiers art, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, wanted to study the great captains of the past to learn how they thought and acted, and how they used the military means at their disposal. He was, he said, less interested in the detailed dispositions than in understanding the essential problem which confronted the general at a certain moment in the battle, what were the factors which influenced his decision, what was his decision and why. In short, he wanted to discover what was in the great mans mind when he made a major decision. This, surely, was the way to study generalship.

This isnt a manual, though. I dont labour the similarities between the six examples. I dont compare and contrast. I dont try to draw over-arching conclusions that are in any way prescriptive. Military savants have been doing that for centuries, and yet in any battle one side always loses there really is no such thing as a drawn battle in the perfect sense so the formula for victory, unlike that for defeat, clearly isnt definitive. (How could it be, given the dialectic and dynamism of war?) The narratives speak for themselves. As Thucydides, the greatest of the ancient Greek historians, wrote: If he who desires to have before his eyes a true picture of the events which have happened, and of the like events which may be expected to happen hereafter in the order of human things, shall pronounce what I have written to be useful, then I shall be satisfied.

As I shall, indeed, if what Ive written simply serves to show what an enigmatic business is war the most complex human interaction ever known.

- . Montgomery of Alamein, A Concise History of Warfare (London, 1972).

- . Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, ed. and trans. Benjamin Jowett (Oxford, 1881).

INTRODUCTION Movement of Bodies

Those of you that have got through the rest, I am going to rapidly

Devote a little time to showing you, those that can master it,

A few ideas about tactics, which must not be confused

With what we call strategy. Tactics is merely

The mechanical movement of bodies, and that is what we mean by it.

Or perhaps I should say: by them.

Strategy, to be quite frank, you will have no hand in.

It is done by those up above, and it merely refers to,

The larger movements over which we have no control

Henry Reed, Lessons of the War (1942)

Modern military theory divides the practice of war warfare into three levels: strategic, operational and tactical. This division has its roots in the Napoleonic Wars, especially the works of two generals in opposing armies: the Prussian Carl von Clausewitz, and the Swiss Antoine-Henri Jomini, who served in the French. These ideas developed further with the American Civil War, and were then codified by the German general staff after the Franco-Prussian War. They reached their practical maturity with the Soviets in the 1930s following the experience of the First World War and Russian Civil War. In Britain, meanwhile, the levels were perhaps more instinctively understood than articulated. It was only really towards the end of the Cold War that anything was promulgated with authority in the 1989 document Design for Military Operations: The British Military Doctrine published by the (Army) General Staff although, as usual with British doctrine publications, it prompted more debate than it resolved.

Field Marshal Montgomery put it this way:

Grand Strategy is the co-ordination and direction of all the resources of a nation, or group of nations, towards the attainment of the political object of the war the goal defined by the fundamental policy. The true objective of grand strategy must be a secure and lasting peace. Strategy is the art of distributing and applying military means, such as Armed Forces and supplies, to fulfil the ends of policy Tactics means the dispositions for, and control of, military forces and techniques in actual fighting.