Mediterranean Naval Battles that Changed the World

Mediterranean Naval Battles that Changed the World

Quentin Russell

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Quentin Russell, 2021

ISBN 978-1-52671-599-9

eISBN 978-1-52671-601-9

Mobi ISBN 978-1-52671-600-2

The right of Quentin Russell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For James Russell MC and Efthalia Russell MBE

Contents

Maps

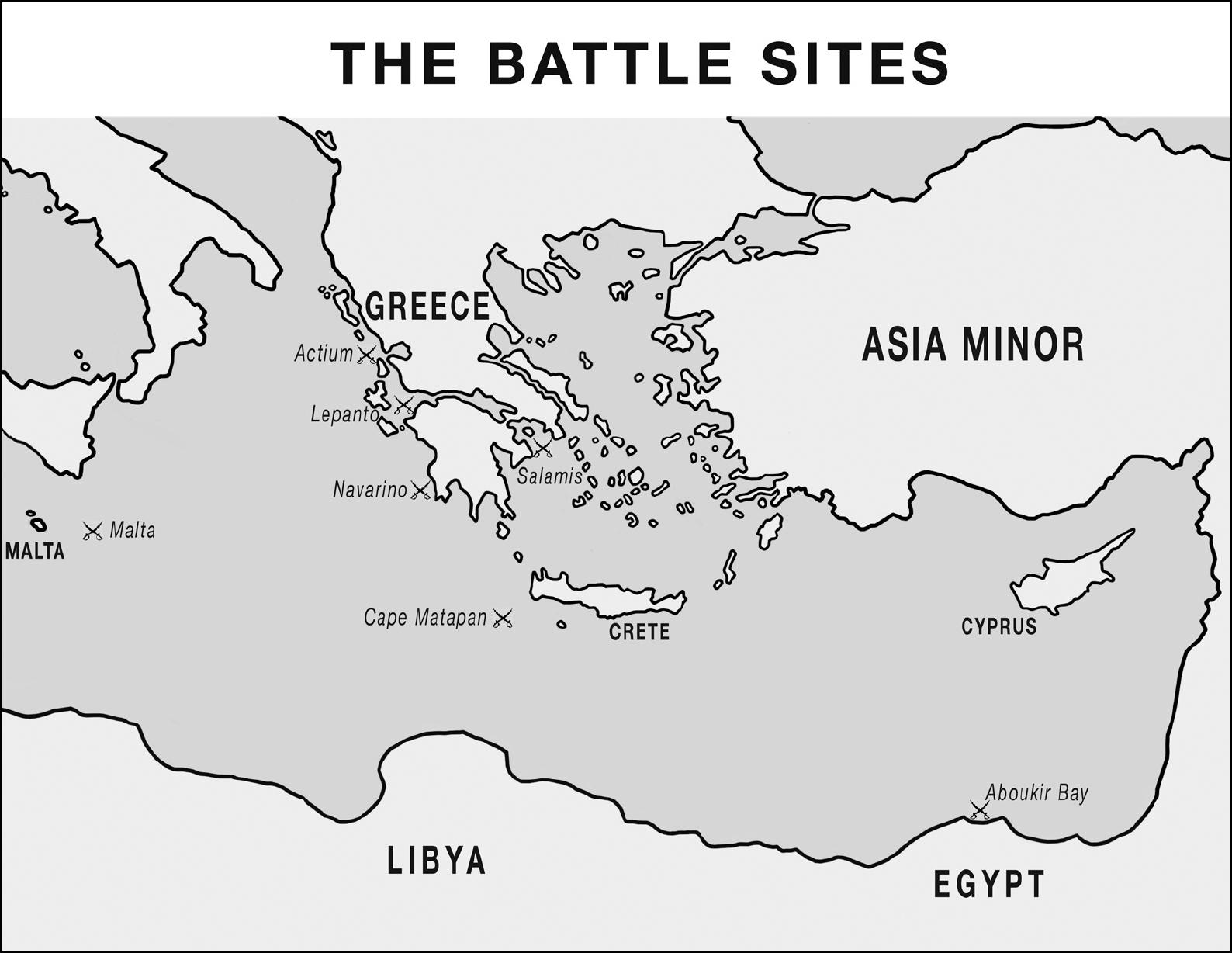

Battle Sites

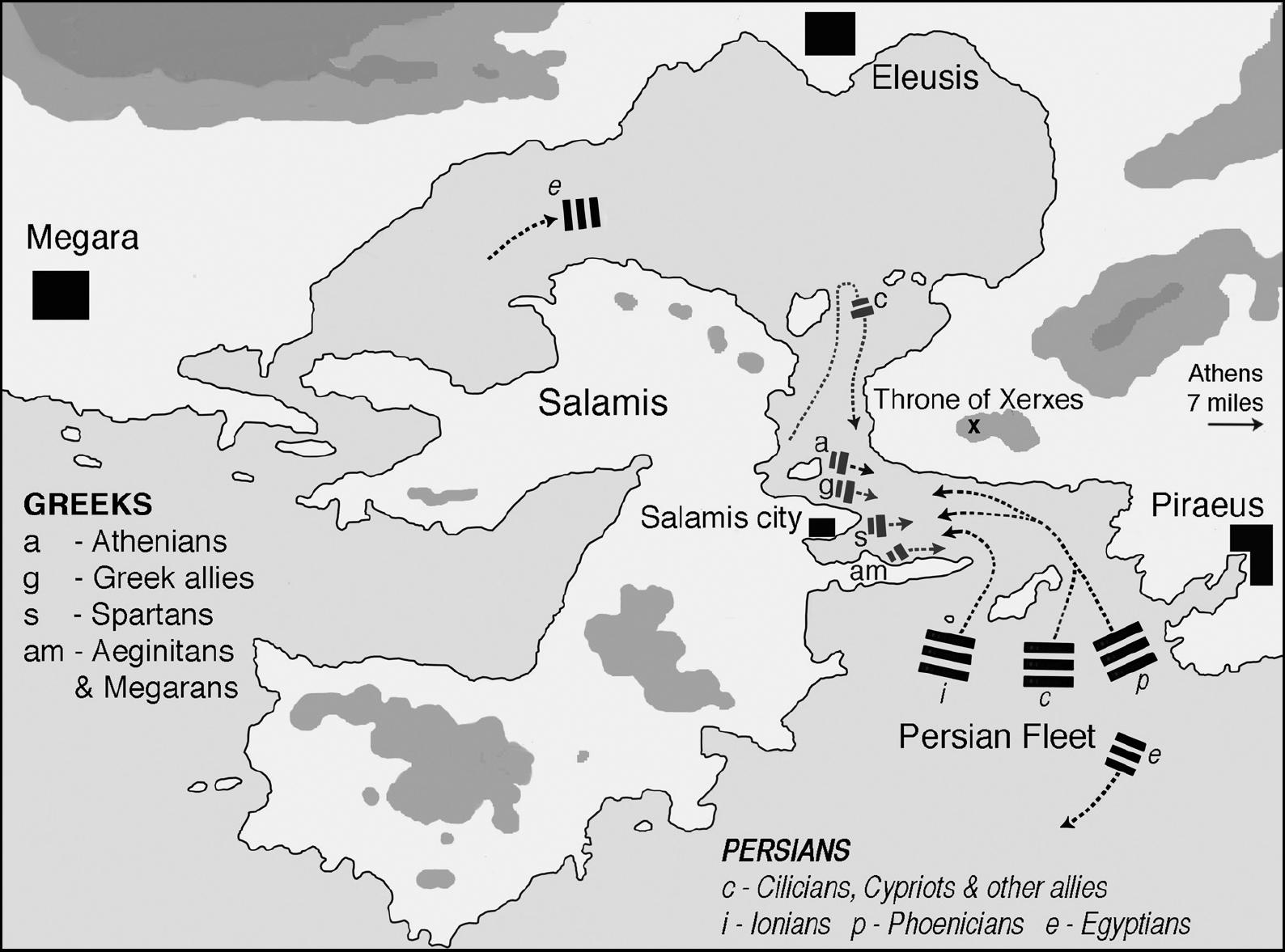

Battle of Salamis

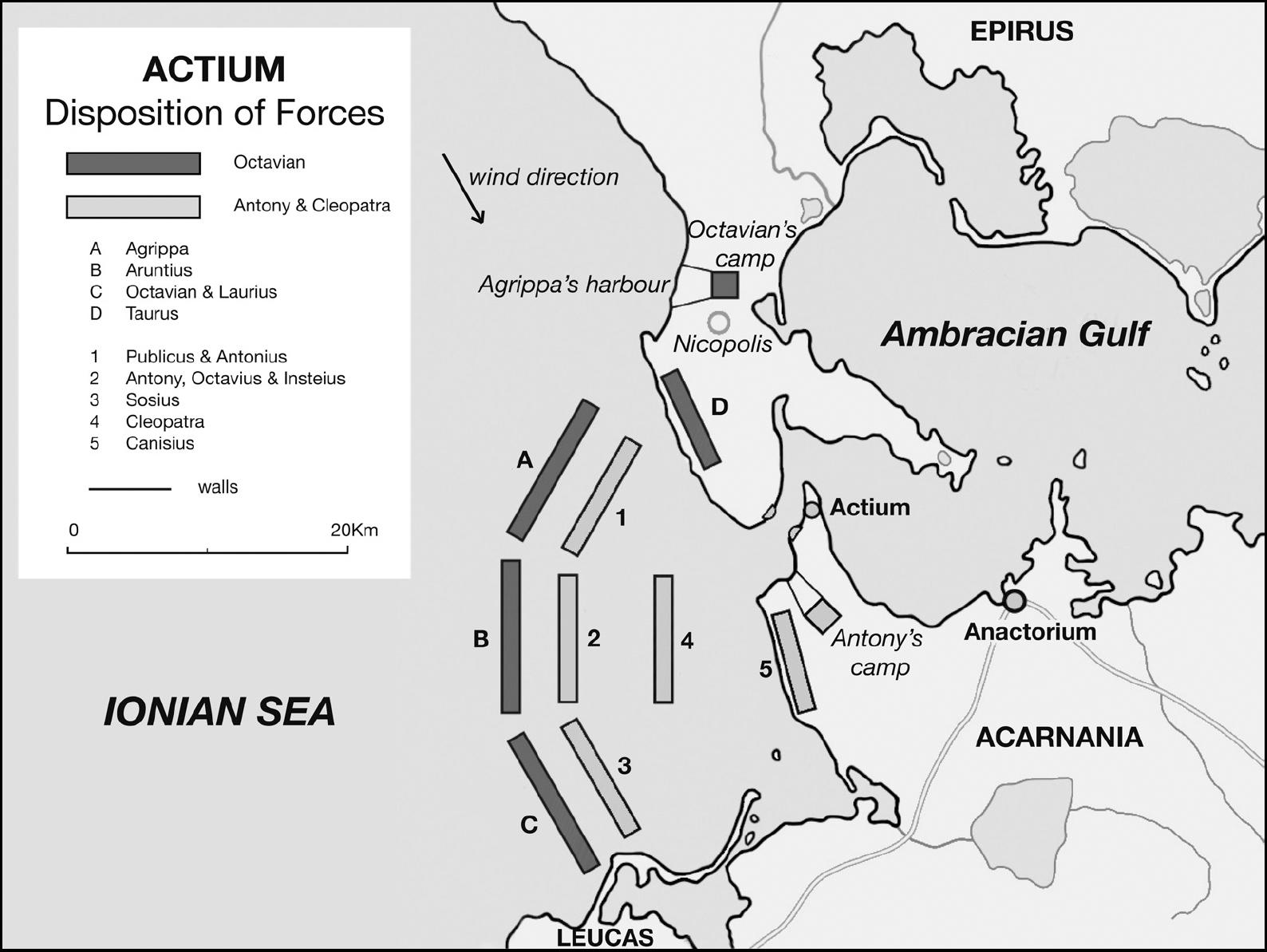

Battle of Actium

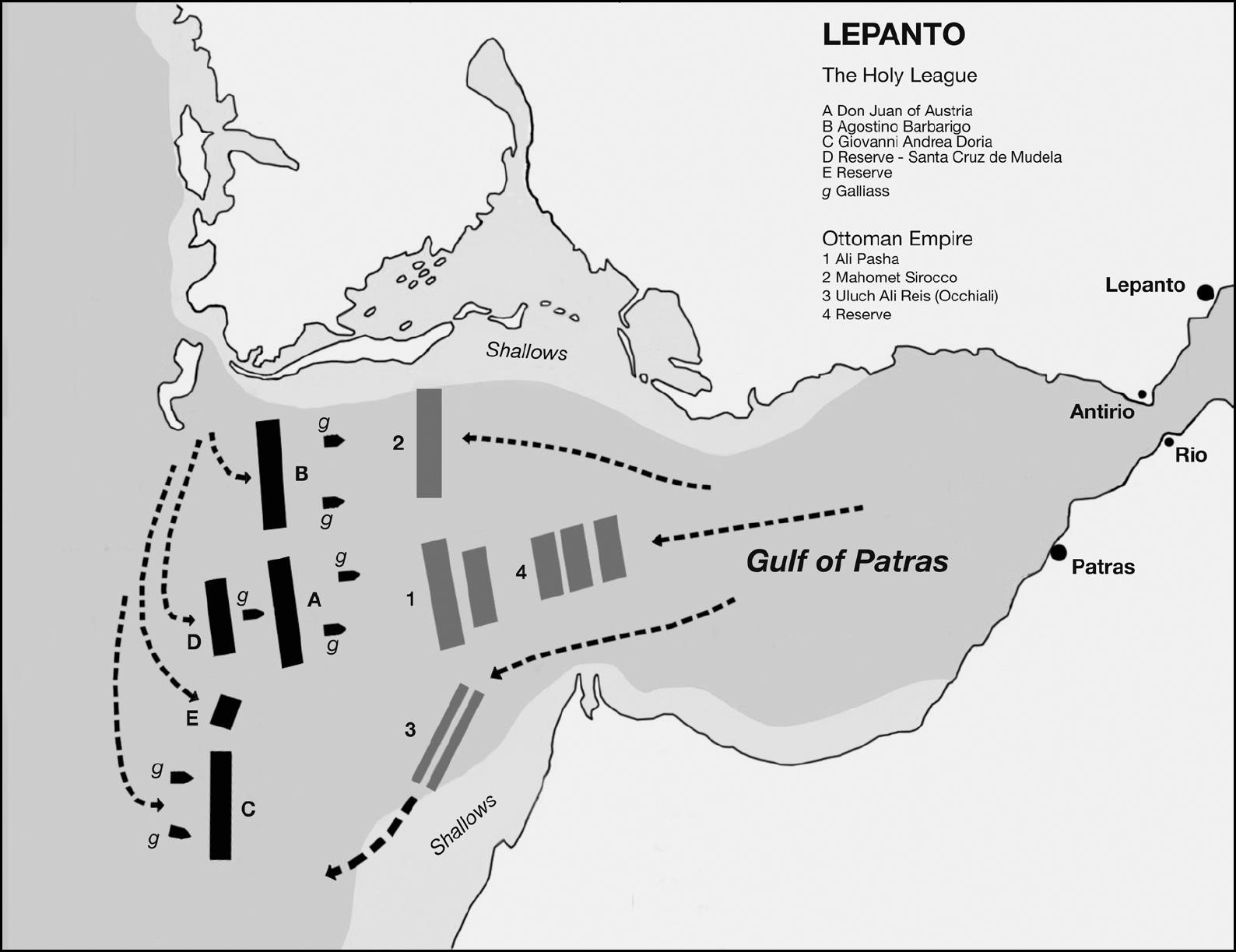

Battle of Lepanto

(All maps Quentin Russell)

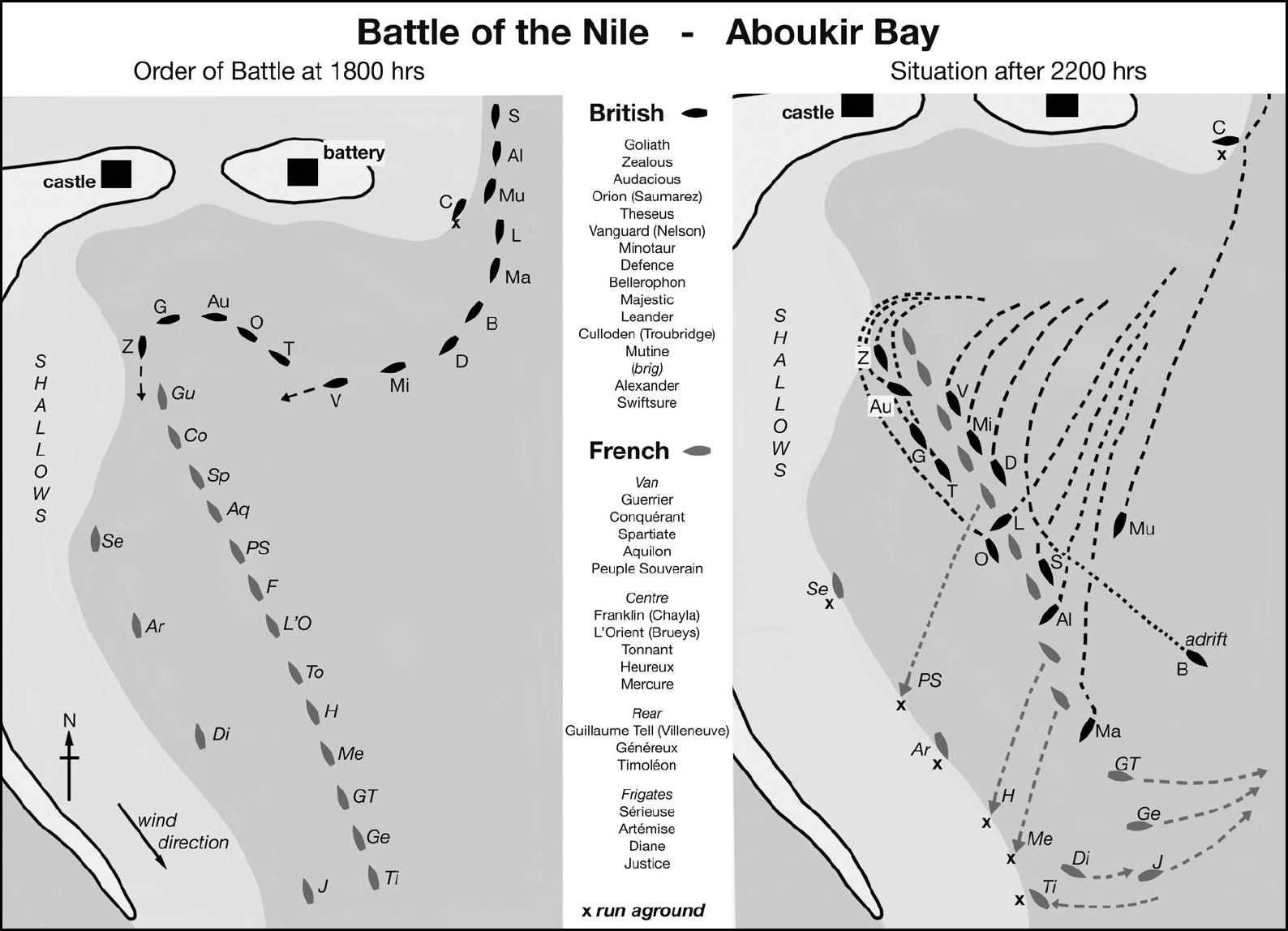

Battle of the Nile Aboukir Bay

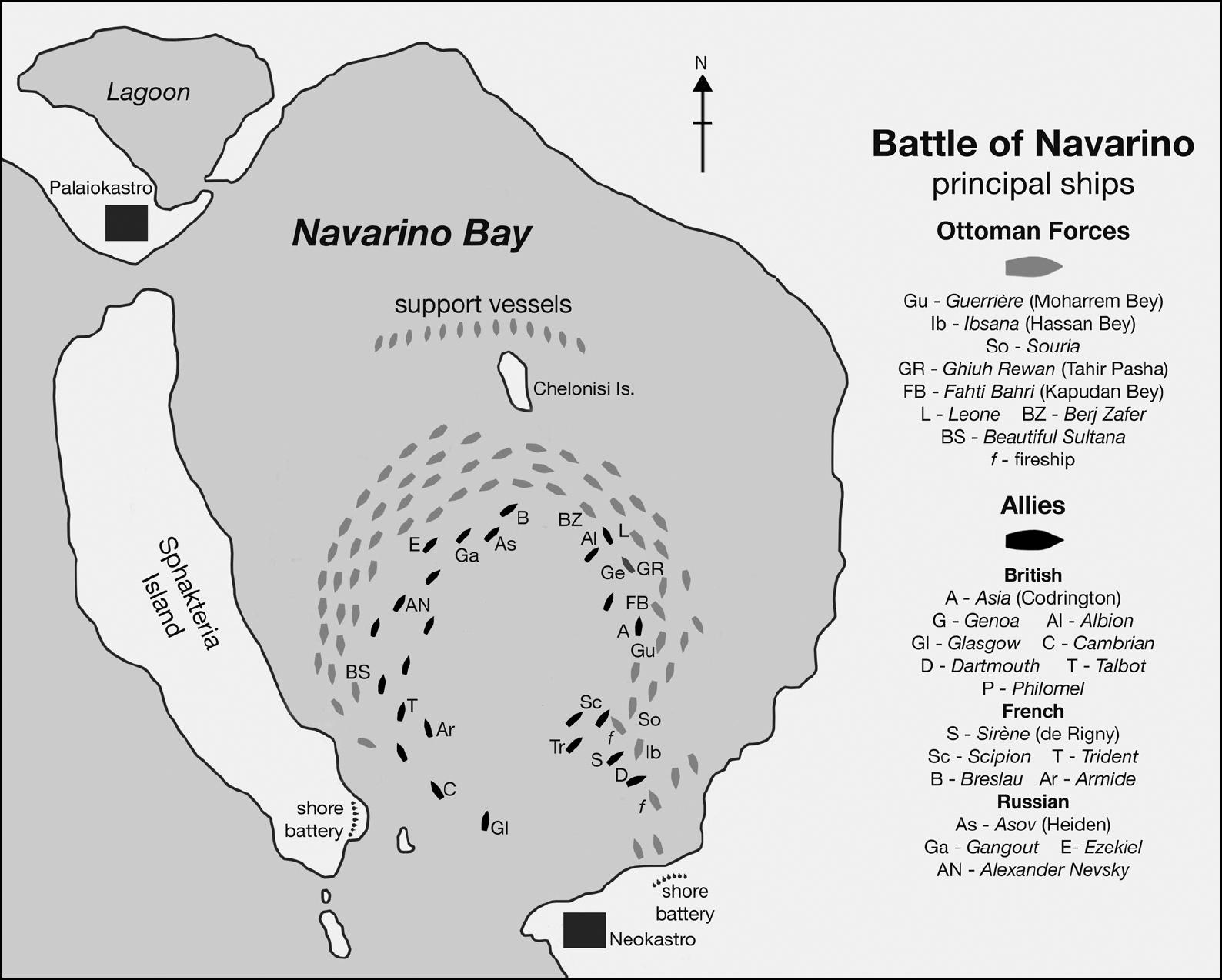

Battle of Navarino

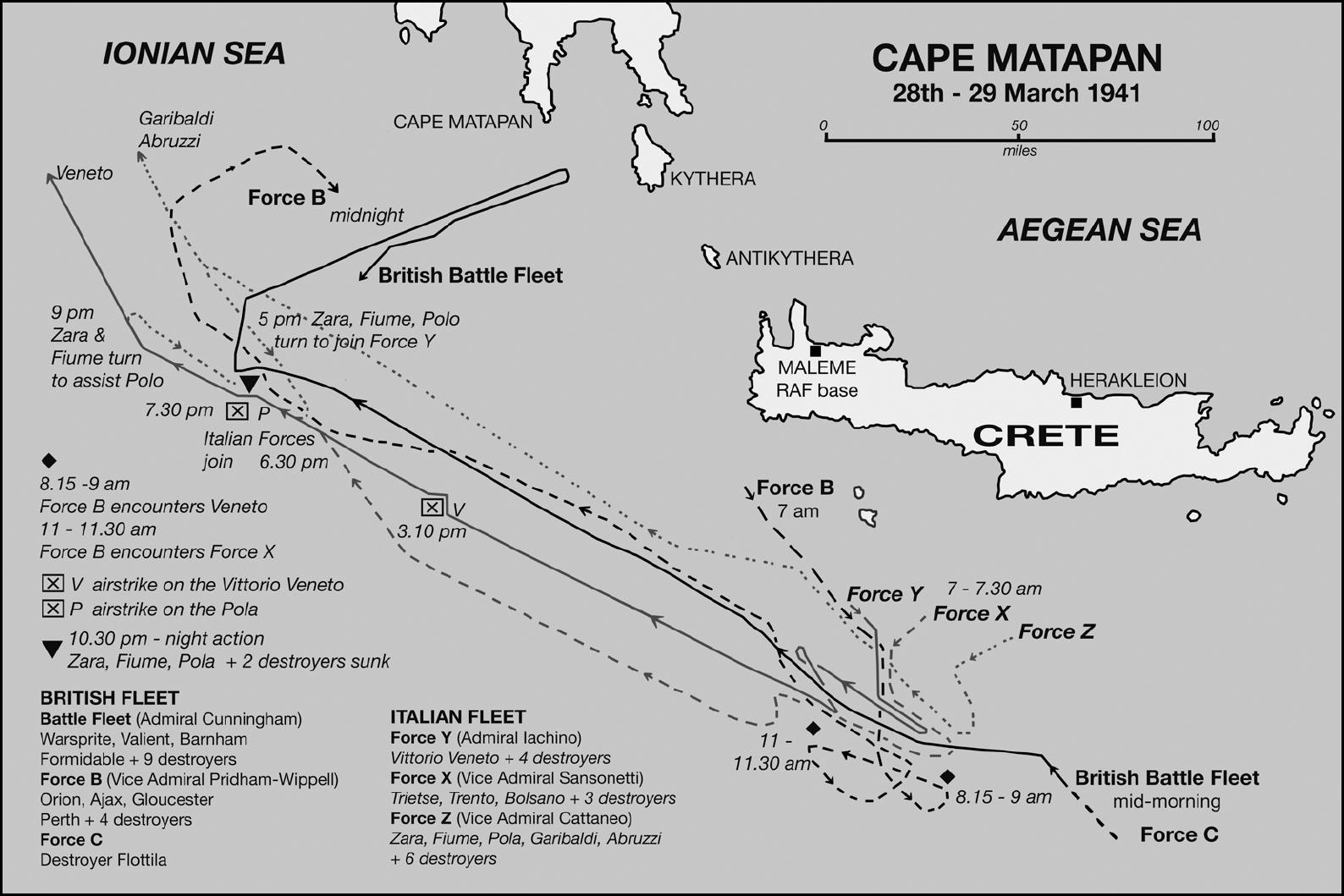

Battle for Malta Cape Matapan

Introduction

The Contested Sea

During his long conflict with Britain, Napoleon Bonaparte often compared France to ancient Rome, and his enemy with Romes obstinate adversary Carthage. This was not only because Rome managed to defeat Hannibal, his favourite general, but also to prove a point. Early in his military career when he was a precocious 19-year-old lieutenant on garrison duty in Auxonne, he reached the conclusion that a nation whose strength is reliant on its navy will always ultimately be defeated by one that is dominantly a military power. Carthage had achieved success through its shipping and commerce, whereas Rome was essentially an agricultural society. Napoleon argued that experience has nearly always shown that the maritime state was vulnerable because warfare destroys its commerce, leading to its exhaustion, whereas on the contrary its opponents are toughened and strengthened.

When his theory was put to the test, despite his many victories it was Napoleons land empire that was defeated. In the end France had proved unable to isolate and wear down Britain because it could not overcome the Royal Navys mastery of the seas, leaving the Duke of Wellington to declare in 1814 that Britains maritime supremacy had enabled him to maintain his army while strangling France. After his defeat and exile to St Helena, Napoleon was forced to concede that the inferiority of the French navy had cost him dearly, but he still maintained that the outcome was not inevitable. The great American naval historian, Alfred Thayer Mahan, writing in 1889, took the opposite lesson from history. Britain by this time was established as the premier naval power in the world and the possessor of a large empire, and it seemed to him that it followed that a naval power would always prevail.

In the West the beginnings of naval warfare start in the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean, being almost completely landlocked and thus the largest inland sea, offered a unique environment for the development of seafaring. At times a barrier and the boundary between continents and cultures, East and West, it was also a conduit for settlement and exchange, providing a highway for trade and ideas, and ultimately colonisers and invaders. The Mediterraneans numerous islands and limited expanses of open water were ideal for the development of the art of seafaring, allowing early mariners the luxury of never having to venture far from land. Once the sea was explored it nurtured communities that looked towards it for their livelihood rather than to the land. Plato noted ( Phaedo 109) that the Greeks had settled around the Mediterranean like frogs around a pond. Centuries later Cicero, in contradiction to Napoleon, put in the mouth of Cato ( De Res Publica 2.10) the sentiment that Romulus had founded Rome on the banks of the Tiber because it gave the city access to the sea (around only 16 miles/26km away), and with the advantages of a coastal city he had the foresight that from this vantage it would become the centre of a world empire.

By then skill at seafaring had become part of the common culture of the coastal civilisations that had grown up around the Mediterranean. Phoenicians and Greeks had left their homelands, searching for raw materials and then land to settle, and founded cities in suitable havens. The Greeks most important colonies were along the coast of Anatolia, where their independent city-states, collectively known as Ionia, became torchbearers of Greek civilisation. There was a long history of conflict for control of the Ionian coast between the Greeks and the native Anatolians and an uneasy relationship of competition and respect grew up between the rival communities. In the 7th century BC, when Lydia became the dominant power in the region, it was the Ionian Greeks who were forced to submit. But Lydias supremacy was short lived. A new and more formidable empire had emerged in the east. The early great empires of the Nile valley and the Fertile Crescent had been created by land armies, and they had been content to halt their expansion at the coast. The Egyptians, although knowledgeable sailors, built their whole society around the fluctuations of the Nile and were little interested in naval power except for defence, whereas this new power, successor to the Assyrians and Babylonians, would not be satisfied merely with taking the coastal cities. The armies of Cyrus the Great of Persia swept all before them, overrunning the Median, Babylonian and Lydian empires and bringing Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Levant under their control. Egypt, that had been the most successful and dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean, fell to Cyrus son, Cambyses II, in 525BC and by the reign of his grandson, Darius I (the Great, 550486BC), Persia was the largest and best-organised empire in the world, stretching from the Indus valley to the shores of the Mediterranean. But Darius was not to be satisfied within the confines of his Asian empire. With his eyes on Europe, he pushed west across the Hellespont in 513BC and invaded Scythia.

Next page