Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed; however, if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright James Holland, 2018

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Keith Burns

ISBN: 978-1-405-92948-6

James Holland

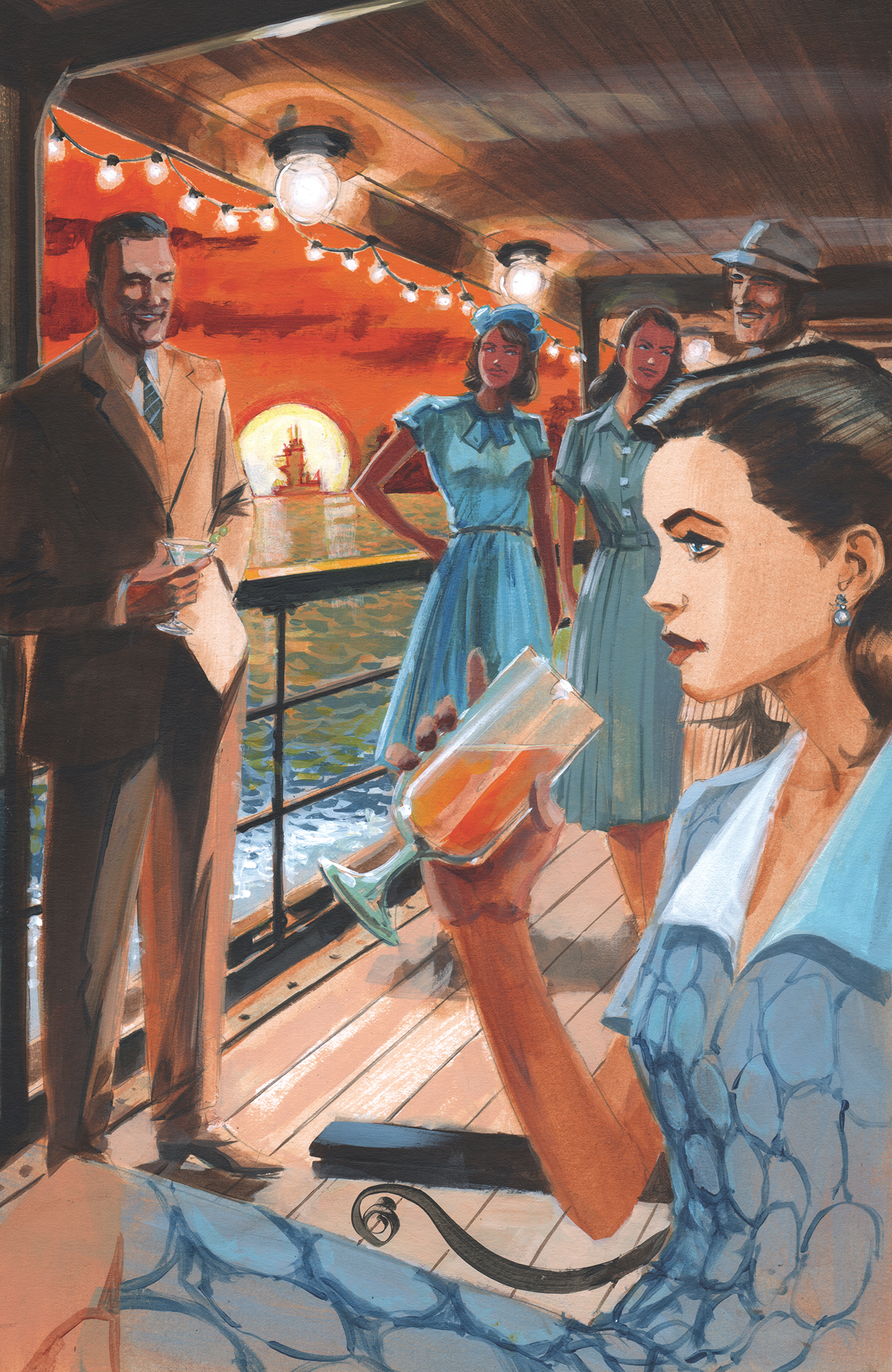

THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC

with illustrations by

Keith Burns

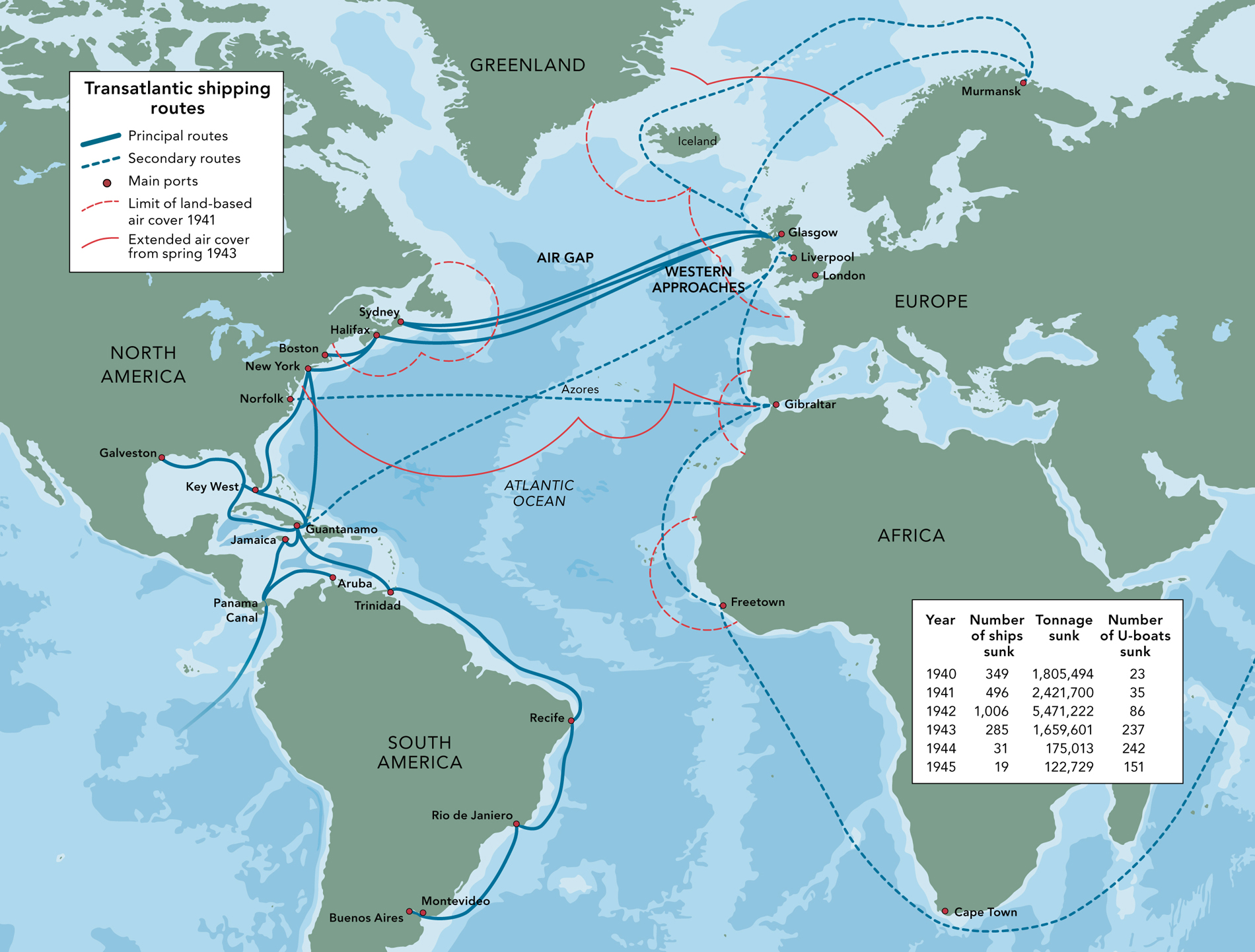

The Atlantic battle began just a few hours after war was declared by Britain and France on 3 September 1939. Some 370 miles north-west of Ireland, a German submarine, or U-boat, U-30, spotted a large vessel steaming west. Lieutenant Fritz Lemp, U-30s commander, was convinced it was an armed merchant cruiser and so opened fire with two torpedoes. These struck at 7.40 p.m., and just after midnight the ship finally sank along with 128 men, women and children. Tragically, the boat was not armed at all, but had been a small transatlantic liner, the SS Athenia, heading to America from Britain with civilians fleeing the war.

It was the start of the longest battle of the entire Second World War, in which ships, submarines and aircraft fought a bitter war of attrition that saw the deaths of over 100,000 servicemen and civilians. Those fighting across these brutal grey seas also fought an ongoing battle with the ocean itself. The Atlantic is a vast and unforgiving place. This was also, in the context of six years of war, possibly the most important battle of them all, because without supplies, warring nations cannot fight. For the Axis forces to defeat the Allies, those supply lines across the ocean had to be severed.

Sinking the Athenia was against Prize rules, which forbade the sinking of civilian passenger vessels during armed conflict and to which Germany had agreed. For Britain, that the ship was sunk by a U-boat also had worrying echoes of the First World War, when German submarines had severely affected the flow of transatlantic supplies. Britain was utterly dependent on seaborne trade, so severing those sea lanes was an overwhelming priority for Germanys war.

At the same time, the Germans also knew that, the moment war was declared, Britains vastly superior navy would impose an economic blockade against Germany which was precisely what they did. This was comparatively easy for the Royal Navy to do because Germany was stuck in central Europe with only a comparatively short coastline, so access to the worlds oceans was very limited.

The most obvious way to break through such a blockade was by submarine. Technology in U-boats had advanced significantly since the last war, and with Germanys poor natural resources and geographical isolation, combined with demands for a large army and air force, it made sense for its navy, the Kriegsmarine, to focus almost entirely on developing as sizeable a U-boat fleet as possible. U-boats were also smaller, easier and cheaper in every regard to build and keep in fuel than a large surface fleet.

Despite this obvious logic, however, Hitler, the German Fhrer, had backed the so-called Z Plan to build a fleet of battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers and destroyers. Only a fraction of these had been constructed by September 1939.

HMS Hood leads HMS Rodney and HMS Renown on manoeuvres on the High Seas.

The British responded to the sinking of Athenia by immediately imposing the convoy system, whereby a mass of merchant ships sailed together protected by escorting warships. These were mostly destroyers: fast, manoeuvrable vessels that were much smaller than the larger cruisers and battleships known as capital ships. Destroyers were equipped with depth-charges mines that sank beneath the surface and then exploded as well as with guns and torpedoes. The theory was that these escorts would provide a protective screen, while the merchant ships would also benefit from safety in numbers. It was very hard to protect a lone vessel sailing across the Atlantic.

Convoys did cause problems, however, because they meant a mass of ships departed and arrived at port at the same time, and needed loading and unloading all at once too. In between, dockworkers had little to do. It was not an efficient use of port facilities, but unquestionably made the ships passage safer.

As German troops swarmed over Poland, the Kriegsmarines new surface fleet was largely stuck behind the British blockade. Not so the U-boats, however. In September, one of the Royal Navys precious aircraft carriers, HMS Courageous, was sunk. Then, in October, in one of the most daring and skilled attacks of the war, Lieutenant Gnther Prien of U-47 managed to slip into the narrow and heavily protected British base at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys and sink the mighty battleship Royal Oak, with the loss of 833 men. It was a severe shock not just to the navy but to Britain as a whole.

These attacks showed all too clearly what a potent force U-boats could be, yet at the wars start Admiral Karl Dnitz, the commander of the BdU, the U-boat arm, had just 57 rather than the 300 for which he had been pleading. Even this small number looked more impressive on paper than it was in reality, because submarines operated to the rule of thirds: one third at sea, one third heading to and from their hunting grounds, and one third undergoing re-equipping and repairs. In all, there were only 3,000 men in the entire BdU and few more than fifty U-boat commanders. Training took time, as did building up the necessary skill and experience. Should Dnitz ever have the chance to increase the size of his force significantly, the pool of manpower for such an expansion was very slight indeed.