The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Bro

Contents

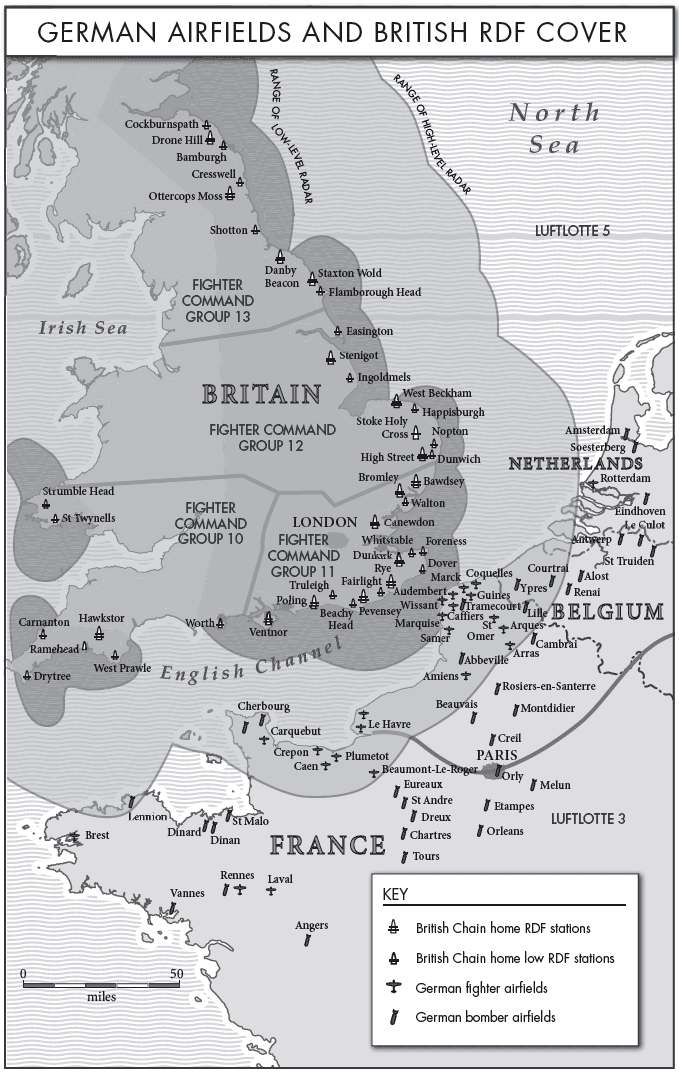

Maps and Figures

RAF FIGHTER COMMAND ORDER OF BATTLE

Groups and squadrons, 8 August 1940 (0900 hours)

(Sector stations in italic)

LUFTWAFFE ORDER OF BATTLE IN THE WEST

AUGUST 1940

Note on the Text

So as not to cause any confusion, I have used German ranks, rather than English translations. I have also called German units by their German names, largely because when writing about something from the German perspective, it seemed odd not to do so. Thus I have called German motor torpedo boats S-boats as in Schnellboote rather than E-boats, as the British termed them.

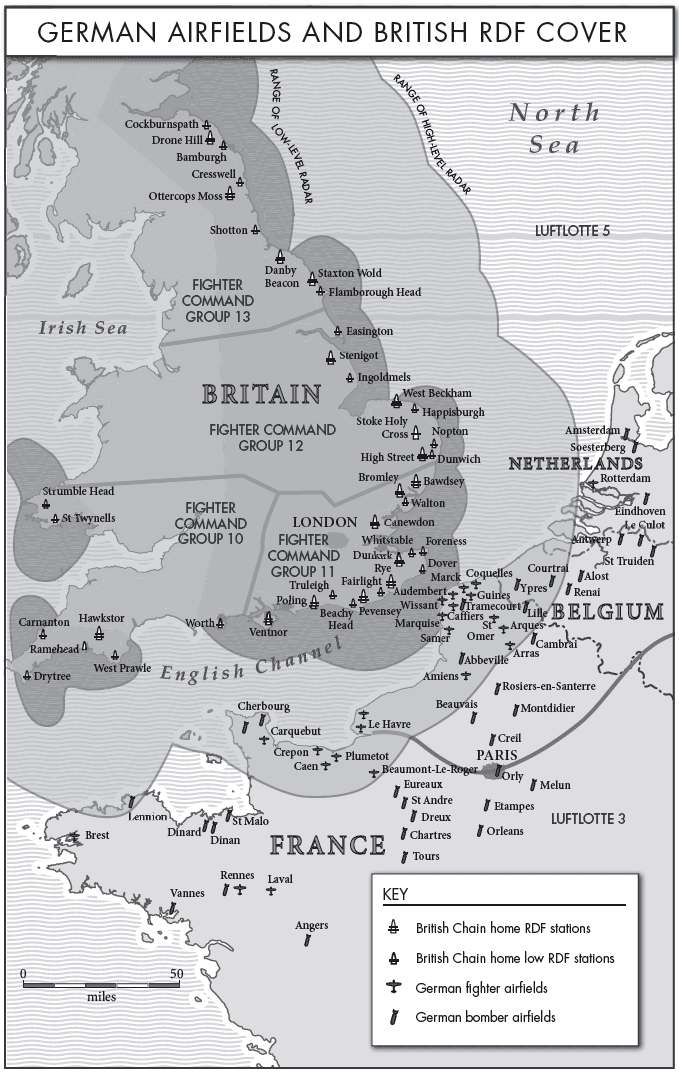

Equally, I have referred to German air units in the German terminology, partly to help distinguish them from British units, but also because their units were not quite the same as those in the RAF. The largest Luftwaffe force was the air fleet, or Luftflotte , and within each Luftflotte were Fliegerkorps (air corps). Beneath that there could even be Fliegerdivisionen . However, the principal air unit was the Geschwader , which contained three Gruppen ; each Gruppe then had three Staffeln . Thus 2/JG 2 was the second Staffel of the first group of Jagdgeschwader 2. A Jagdgeschwader was a fighter unit, a Kampfgeschwader a bomber unit. Staffeln were always labelled with Arabic numbers, Gruppen by Roman numerals. Thus III/KG 4, for example, was the third Gruppe of Kampfgeschwader 4. A fighter Staffel would have a theoretical establishment of twelve aircraft, but usually an operational number of nine. A bomber Staffel would have a theoretical establishment of nine, and an operational number of one or two less.

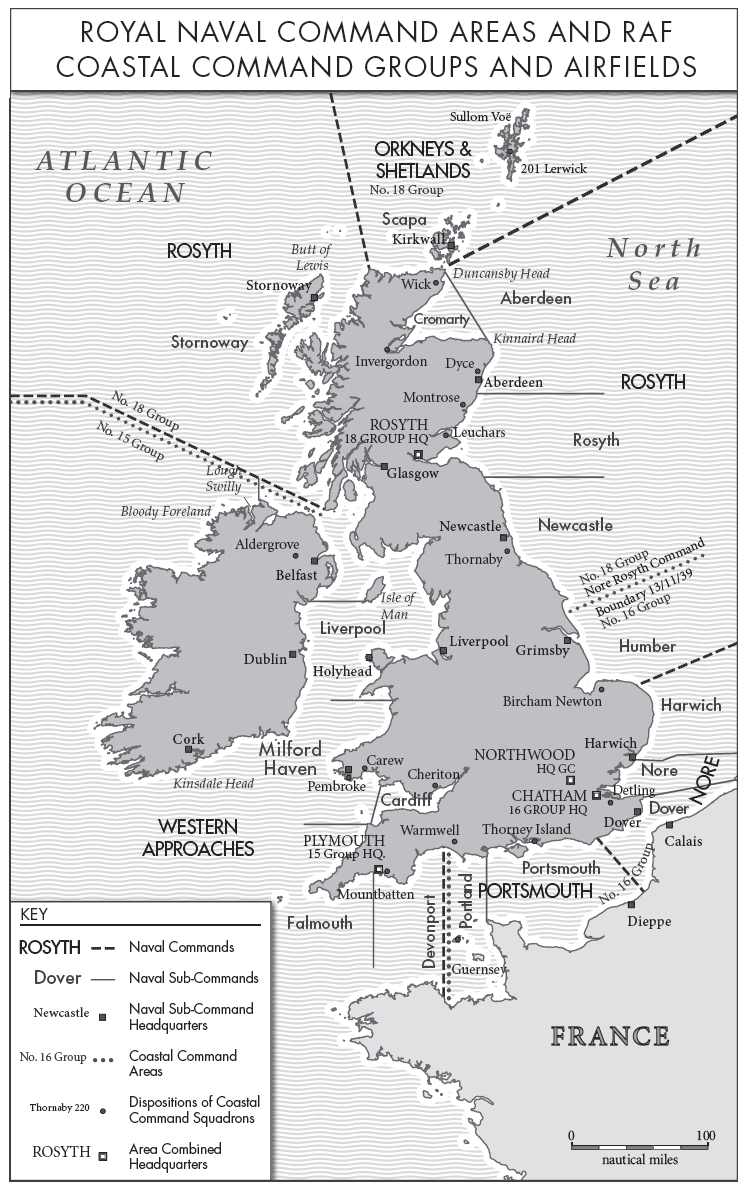

The RAF did not have an organization based on army structure, but rather was separated into commands, which from Britain were divided into Fighter, Bomber, and Coastal Commands. The principal unit within these commands was the squadron. Fighter squadrons had a theoretical establishment (IE or immediate establishment) of sixteen aircraft, of which at least twelve would be operational. They also had an IE of twenty pilots.

Introduction

T HE B ATTLE OF B RITAIN began for me in the Autumn of 1939, wrote Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding in his despatch; after all, that was when Britain and Germany went to war. In the end, however, he opted rather arbitrarily for 10 July 1940 as its starting point, the day the Germans first attacked southern England with a large formation of some seventy aircraft. Dowding was referring to RAF Fighter Commands role that summer and his despatch set the benchmark for how the great aerial clash over Britain has been viewed ever since.

Yet his Spitfires and Hurricanes first properly tussled with the Luftwaffe in May that year, over France, while the intense battle between the two sides was far more all-encompassing than an account of the clash in the air suggests. At every level, from the corridors of power to the man in the street, and from the Field Marshal to the private, or from the skies above to the grey swell of the sea, those summer months of 1940 were a period of extraordinary human drama, of shifting fortunes, of tragedy and triumph a time when the world changed for ever. For Britain, her very survival was at stake; for Germany, the quick defeat of Britain held the key to her future. For both sides, the stakes could not have been higher.

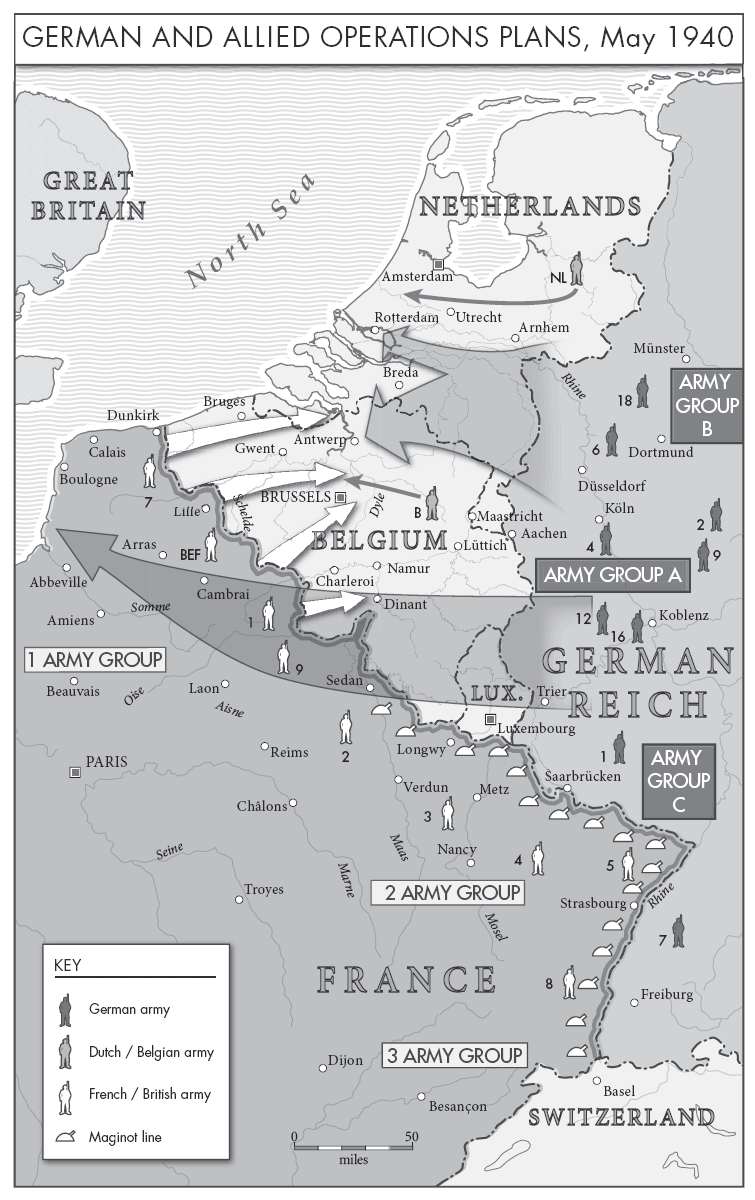

The time has come to look at those critical months afresh. Dowding was possibly stretching the point too far in suggesting the Battle began with the outbreak of war. But it was with the launch of the western campaign that Britain began to face the worst crisis in her history, while for Germany 10 May 1940 marked, inextricably, her crossing of the Rubicon. The point of no return.

In these five critical months, the battle encompassed warfare on land and at sea as well as in the air, whilst the British and German governments fought their own political and propaganda battles as well as one for intelligence, all of which had a profound impact on the unfurling events. In isolation, these differing aspects only present part of the story. Together, new and surprising perspectives emerge.

Truly, the Battle of Britain is an incredible story, and even more so when the full picture is revealed. Rarely has there been a more thrilling episode in history.

S UNDAY , 5 M AY 1940, a little after two that afternoon. A warm, sunny day over much of Britain, but above Drem aerodrome, a busy grass airfield some twenty miles east of Edinburgh, a deep blue sky was pock-marked with bright white cumulus drifting lazily across the Scottish headland on a gentle breeze. Perfect flying weather, in fact, which was just as well because Pilot Officer David Crook could barely contain his excitement any longer.