ALSO BY CLAUDIO SAUNT

A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the

Transformation of the Creek Indians, 17331816

Black, White, and Indian: Race and the

Unmaking of an American Family

Copyright 2014 by Claudio Saunt

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2015

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by JAM Design

Production manager: Julia Druskin

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Saunt, Claudio.

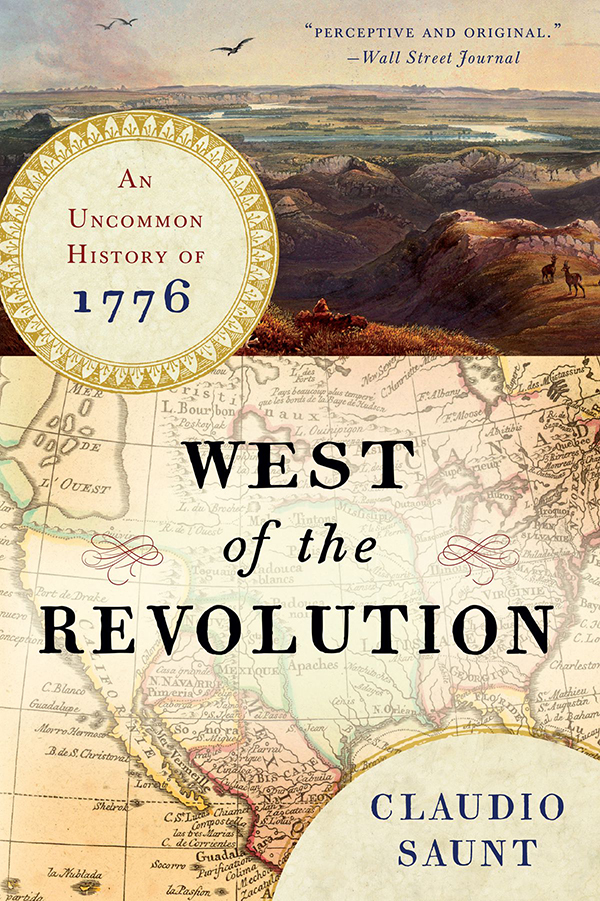

West of the Revolution : an uncommon history of 1776 / Claudio Saunt.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-24020-7 (hardcover)

1. United StatesHistory18th century. 2. AmericaColonizationHistory.

3. AmericaDiscovery and explorationSpanish. 4. EuropeColoniesAmerica.

5. Indians of North AmericaHistoryRevolution, 17751783.

6. EuropeansAmericaHistory. 7. North AmericaDescription and travel.

8. West (U.S.)Discovery and exploration. 9. West (U.S.)History18th century.

I. Title. II. Title: Uncommon history of 1776.

E303.S28 2014

973.3'13dc23

2014011360

ISBN 978-0-393-24430-4 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-393-35115-6 pbk.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

WEST

of the

REVOLUTION

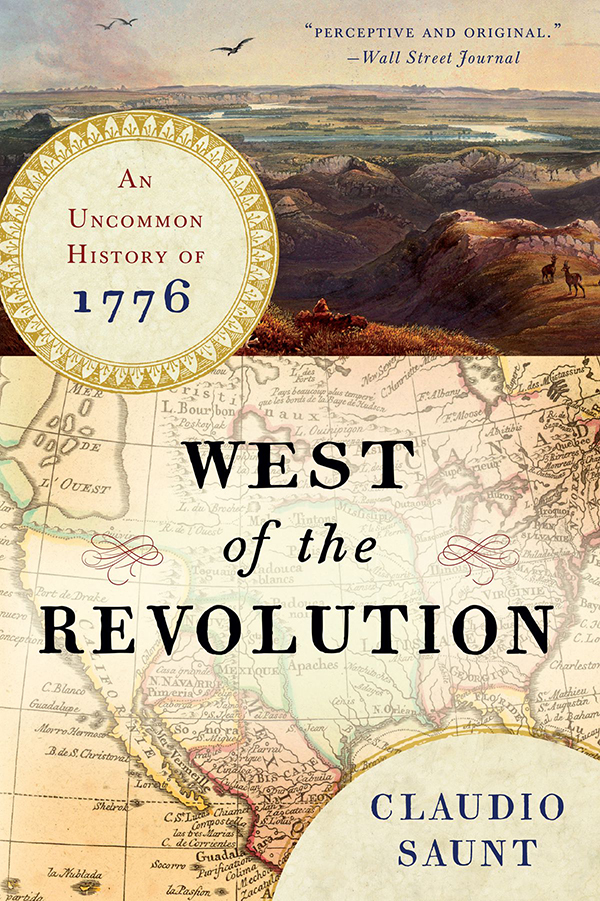

T here is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island, declared Thomas Paine in Common Sense, his famous pamphlet that galvanized American revolutionaries in 1776. The war was not the affair of a city, a county, a province, or a kingdom, he claimed, but of a continentof at least one eighth-part of the habitable globe. That eighth became, in the words of patriot David Ramsay, fully a quarter of the globe, waiting to be redeemed from tyranny and oppression. We know how the story of that redemption unfolded, even if we are sometimes hazy about the particulars. The American Revolution so dominates our understanding of the continents early history that only four digits1776are enough to evoke images of periwigs, quill pens, and yellowing copies of the Declaration of Independence. Yet the colonies that formed the Continental Congress and filled the ranks of the Continental Army (paying men in Continental currency) made up only a tiny fraction of the actual continentjust under 4 percent of North America, to be more precise.

In 1776, formative events were occurring not just along the Eastern Seaboard but across all of North America. In Alaskas Aleutian Islands, Russians were destroying Aleut villages. In San Francisco, native residents and Europeans made contact for the first time ever. Down the coast in San Diego, Kumeyaay Indians rose up against the Spanish, and participants spent months afterward dealing with the consequences of the failed revolt. That same year, the Sioux discovered the Black Hills. To many Americans, these stories are almost entirely unknown, as surprising and unpredictable as events that we watch transpiring in the present moment. They are the subject of West of the Revolution.

I grew up in San Francisco, twenty-five hundred miles from Boston and the seat of the American Revolution. San Francisco did not exist when British soldiers and American Minutemen met in battle at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. In late June 1776, a week before Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, Jos Joaqun Moraga built a small shelter of branches on the banks of a lagoon that the Spanish called Arroyo de los Dolores. The site became Mission Dolores, the first colonial settlement in San Francisco. While the young republic took shape on the opposite side of the continent, San Francisco moved in its own direction. In 1808, shortly before James Madison became the fourth president of the United States, Ivan Kuskov, an employee of the Russian-American Company, secretly buried a copper plate in San Francisco that read, Land belonging to Russia. Four years later, he would found the Russian outpost of Fort Ross less than one hundred miles to the north.

As a child who was more interested in music than in the past, I remained ignorant of the history of my birthplace for many years. My summer music camp was located on the Russian River, which drains into the Pacific Ocean a few miles south of Fort Ross. For too long, I puzzled over the name: was it the Rushing River or the Russian River? The Rushing River seemed more plausible. As far as I understood, the Russians had nothing to do with California, and dropping the final g made perfect sense to a would-be jazz musician. After all, my favorite Miles Davis albums at the time were the classic LPs Workin, Steamin, Relaxin, and Cookin. Of course the river must have been Rushin.

There is further evidence of my historical ignorance. When I was eight and the Bicentennial of the United States rolled around, I was delighted to go on a field trip to see the worlds largest birthday cake, which was illustrated with scenes from the American Revolution and had been trucked across the continent to San Francisco. At least, that is how I remember it. Reading through the historical record, I find a slightly different account of the festivities. The three-tiered, six-sided, revolving cake was indeed enormous, rising thirty feet (not counting the five-foot phoenix mounted on the top), and weighing in at 17.5 tons. But the monstrosity never crossed the continent, and its eighteen panels did not illustrate the Revolution, as I had remembered. The cake, made by a local pastry chef to celebrate San Franciscos own bicentennial, instead commemorated events from the citys history, beginning with Francis Drakes discovery of the bay and including the arrival of the Spanish. San Franciscos history was at such odds with the narrative being celebrated for the national Bicentennial that my fourth-grade imagination turned the cake into a tribute to events in Boston, Philadelphia, and elsewhere along the East Coast.

My misconceptions about the Russian River and San Franciscos bicentennial surely suggest that I did not pay enough attention in elementary school, but they are also symptomatic of a broader phenomenon. Americans are generally unacquainted with the early history of their continent beyond the thirteen British colonies that formed the United States. Like the foreshortened continent in Saul Steinbergs famous New Yorker cover View of the World from 9th Avenue (Figure 1), early America recedes rapidly from our historical consciousness as we look west, vanishing at a horizon only a few hundred miles from the Atlantic Coast.

In contrast to that provincial perspective, it is possible to envision early America as stretching from one coast to the other and encompassing all the people who lived there. This exciting prospect reveals vast lands and multitudes of North Americans whose stories are unfamiliar to us. We have an intimate connection to those lands; we live on them, yet know little about their early history.

Next page