I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation for the help received from the following individuals, organisations and associations, without whom this book could not have been realised. I trust that I have not in error missed anyone who assisted me and would offer my sincere apologies, should that be the case.

Lindsay Bridge, Nereo Castelli, Eugen Chirva, Mario Cicogna, Amos Conti, Frank Heine, Richard de Kerbrech, Rei Kimura, Knut Klippenberg, Arnold Kludas, Enoki Koichi, Siri Holm Lawson, Boris Lemachko, Michael Lynch, Rolf Meinecke, Dr Piotr Mierzejewski, Mervyn Pearson, Bjrn Pedersen, Luca Ruffato, James Shaw, Yan Shuheng, Erling Skjold, Peter Tschursch, Kihachiro Ueda and Ray Woodmore.

Bundesarchiv (Martina Caspers)

Deep Image Co. (Leigh Bishop)

Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum (Klaus Fuest)

French Line Archives (Pauline Maillard and Nancy Chauvet)

Glasgow University Archives (William Bill and Gemma Tougher)

Guildhall Library, Aldermanbury, London (Valerie Hart)

Hapag-Lloyd (Peter Maass)

Imperial War Museum

JAMSTEC (Noriko Kunugiyama)

John Swire & Sons (Rob Jennings)

Lancastria Survivors Association

Maritime Photo Library (Adrian Vicary)

Mitsui-OSK (Yasushi Kikuchi)

Nippon Yusen Kaisha (Captain Masaharu Akamine)

Ostsee Archiv (Heinz Schn)

PoW Research, Japan (Toru Fukubayashi and Yuji Miwa)

Press Association (Jane Speed and Laura Wagg)

Royal Navy Submarine Museum (Debbie Corner)

The National Archives, Kew

United States Navy

University of Bristol (Professor Robert Beckers and Jamie Carstairs)

University of Liverpool, Cunard Archives (Dr Maureen Watry)

World Ship Society Photo Library (Jim McFaul & Tony Smith)

CONTENTS

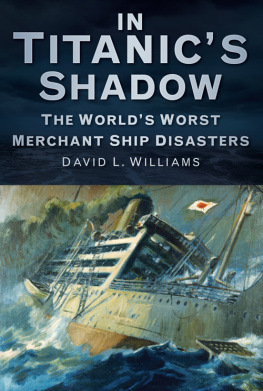

F our days after leaving Southampton on her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912, the White Star Lines new flagship, RMS Titanic , struck an iceberg near the Grand Banks, off Newfoundland, and foundered with the loss of 1,507 lives. The disaster sent shock waves around the world and brought about many important yet long overdue improvements to the rules governing maritime safety. Since that time, there has been an enduring fascination with the tragedy, not least because it was claimed the ship was virtually unsinkable and, having been perhaps influenced by such thinking, because there was an inadequate number of lifeboats to rescue all the people she was carrying. The sinking of the Titanic rapidly became a metaphor for extreme calamity, especially of a maritime nature, and, ironically, her name has been used as a means of conveying the gravity of far more serious events. Hence, we have Asias Titanic , The Titanic of Germany, and so on.

The Titanic story has been told and retold countless times in books and films, so that to each new generation it has become a familiar fable; warning of the consequences of human arrogance and of taking lightly the ever-present dangers of the seas. From this emerged the misconception that the sinking of the Titanic was the worst shipping disaster ever, a belief still widely held today, overshadowing many other equally or more serious maritime losses. Indeed, a comparable tragedy that occurred barely two years later, when the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Ireland was run down and sunk in the St Lawrence Seaway, is nowhere near as well known, certainly outside shipping circles, even though 1,098 lives were lost. Although the approaching First World War in part deflected attention away from this second great catastrophe, the impact of the Titanic s loss on the public consciousness had somehow made it easier to accept this equally grave event.

During the First World War, the relentless migration to total war, with seemingly diminishing regard for casualties and in which, for the first time, civilians became legitimate targets, heralded the potential for even greater slaughter on the oceans. While the Titanic disaster remained, briefly, the most serious deep-sea maritime accident, the destruction by torpedo of ships like the Lusitania and Gallia , with extremely high casualties, was a clear indication of things to come. It was in this conflict that the Titanic s horrendous death toll would be surpassed, while in the Second World War that followed only twenty years later, the margin by which it was to be exceeded would grow alarmingly.

While it is not the intention of this book to diminish the gravity of the Titanic disaster, it is nevertheless fitting at the time when the 100th anniversary of that loss is being commemorated, once more giving it a singularly disproportionate focus, that the losses of those ships that subsequently suffered higher casualties should receive greater recognition. The disparity of attention between these events can be best demonstrated by an experience I had while researching for this very book. A search in a well-known, specialist maritime reference library for any literature on any of the ships described in this volume drew an almost complete blank, whereas there was an entire rack of books devoted to the Titanic alone.

By raising the profile of these other losses, it sets the Titanic disaster in a broader context. This approach, while perhaps relegating Titanic and giving it a less extraordinary status, highlights how in peacetime, despite international conventions, the regard for passenger safety has been increasingly compromised for the sake of commercial competition and operational economics, and, in wartime, how human life has been callously cheapened.

As already alluded to, the ships described in these pages, more than forty in total, all suffered significantly worse human casualties when they were sunk than had the Titanic . In some cases, the number of victims was three or four times greater. In total, they account for a death toll of 140,000; a staggering loss of life at sea and an average of 3,250 people killed with each sinking. Thus, while it is not the intention to suggest that the Titanic case should not receive the attention it does, these far less well-known tragedies do give the so-called worst disaster at sea a sobering perspective.

Despite the fact that the Titanic disaster now ranks far behind many other merchant ship casualties in terms of lost life, these other ships remain, in comparison, largely inconspicuous and unknown, hidden from the media spotlight. There are many reasons for this. If we consider first, by way of contrast, the greater public awareness of the Titanic tragedy and, for the purposes of the exercise, disregard its appalling consequences, it can be seen that it had an almost theatrical dimension with all the drama and human interest of a well-plotted novel. It could almost have been conceived as a screenplay or bestseller, with its vivid characters and a gripping storyline advancing relentlessly to its awful climax. Oblivious to the impending danger, each facet of the ships vulnerability is sinisterly revealed; also, there is the contrast between the prospects for survival of rich and poor as they confronted eternity; a contrast with underlying themes of morality and social injustice.

On the other hand, this is not so for the majority of the ships and incidents described herein. Sunk mainly in wartime while carrying troops, prisoners or evacuees, they lacked the glamorous image that was an integral part of the Titanic s story. Grey ships on grey oceans, sparsely reported due to the restrictions of news embargoes imposed at the time in many cases little more than the barest of facts was ever recorded about these major shipping disasters. Moreover, if we take into consideration the fact that around 85 per cent of these losses involved enemy ships, although not in all cases enemy personnel, it becomes clear there was far less concern about the severity of the loss of life. It was a case of: we were fighting a war; in wartime people get killed; and these victims were invariably enemy people and not our concern.

Next page