Published in 2018 by Enslow Publishing, LLC.

101 W. 23rd Street, Suite 240, New York, NY 10011

Copyright 2018 by Enslow Publishing, LLC.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Crompton, Samuel Willard, author.

Title: How Woodrow Wilson fought World War I /Samuel Willard Crompton.

Description: New York : Enslow Publishing, 2018. | Series: Presidents at war | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grades 712.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004615 | ISBN 9780766085299 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: Wilson, Woodrow, 18561924Juvenile literature. | World War, 19141918United StatesJuvenile literature. | United StatesPolitics and government19131921Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC D766 .C76 2018 | DDC 940.3/73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004615

Printed in the United States of America

To Our Readers: We have done our best to make sure all website addresses in this book were active and appropriate when we went to press. However, the author and the publisher have no control over and assume no liability for the material available on those websites or on any websites they may link to. Any comments or suggestions can be sent by e-mail to .

Photo Credits: Cover (Wilson), pp. Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo.

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 WILSON BEFORE THE CONGRESS

CHAPTER 2 WILSON THE MAN, WILSON THE PRESIDENT

CHAPTER 3 THE FIRST WORLD WAR BEGINS

CHAPTER 4 FROM NEUTRALITY TO BELLIGERENCE

CHAPTER 5 ADMIRALS AND GENERALS

CHAPTER 6 THE WAR AT HOME

CHAPTER 7 THE CRISIS

CHAPTER 8 THE FINAL PUSH

CHAPTER 9 THE BIG FOUR

CHAPTER 10 WILSONS LEGACY

CONCLUSION

CHRONOLOGY

CHAPTER NOTES

GLOSSARY

FURTHER READING

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

I n the summer of 1914, America, and most of the rest of the world, was at peace. To be sure, there were tensions and flare-ups between various nations. But the overall theme was one of peace and the expectation that it would continue.

Forty-nine years had passed since the end of the Civil War, and in all that time Americans had not been called upon for any serious wartime sacrifices. The Spanish-American War, in 1898, had been a relative piece of cake, with the United States gaining large amounts of territory for rather little loss of life (more had died from disease than battle wounds). The various Indian Wars on the Great Plains had entailed no significant loss of life. Where foreign relations were concerned, a majority of Americans felt blessed.

Much, but not all, of this changed in the summer of 1914, when two great alliance systems went to war in Europe. The Allied Powersconsisting of Britain, France, Russia, Serbia, and a number of otherswent to war against the Central Powersconsisting of Imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire. Americans watched with horror, and some fascination, as the various Great Powers of Europe seemed determined to destroy each other.

This map shows where the men of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) landed in France, and the routes they took thereafter.

Americans were glad to have a steady hand on the national tiller. Woodrow Wilson had only been in office a year and a half, but he demonstrated great calm as the Great War commenced. The son and grandson of Presbyterian ministers, Wilson believed that thisthe second decade of the new centuryrepresented a turning point in the affairs of humankind. Surely, he reasoned, the various peoples of Europe would come to their senses. Eventually they would recognize the benefits of peace, and he would be in a unique position. As the leader of the only nation which did not seek money, territory, or both, Wilson would act as the honest broker between the two sets of alliances, and bring the Great War to an end.

If anyone could have pulled this off, Woodrow Wilson was that man. The American president possessed great intellect, as well as an abiding faith that God was the author of history. Wilson had tremendous willpower, and his ability to move the average person with his speeches was unrivaled among the major leaders of the day.

But it was not to be. Too many powers had invested too much blood and treasure in the war. Therefore, with each passing month, the battlefield casualties increased, and the bitterness between the various nations rose. By 1916, the year Wilson was reelected to the presidency, millions of lives had been lost.

From his vantage point in Washington, DC, Wilson observed a terrible tragedy unfolding. Every man left dead on the battlefield increased the likelihood of future wars, whichthanks to technological advanceswould be even more destructive. Therefore, in the late winter of 1917, the American president made up his mind. In order to help ensure future peace, he would propel his countrymen white and black, immigrant and native borninto the most destructive war the world had ever seen.

WILSON BEFORE THE CONGRESS

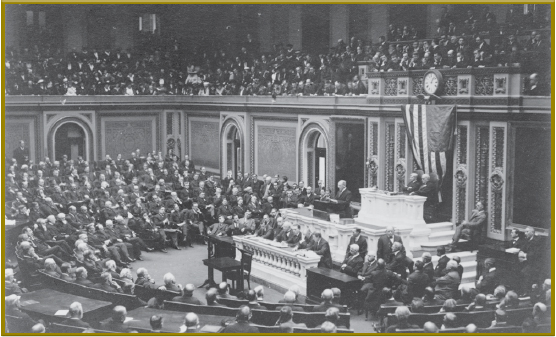

A light drizzle of rain fell on Washington, DC, during the afternoon of April 2, 1917. Residents of the American capital city were not surprised or dismayed. The winter had been severe, and spring was later than usual. The really big news was not the weather, but the knowledge that President Woodrow Wilson would address both Houses of Congress at 7:30 p.m.

That the president would ask Congress for a declaration of war against Imperial Germany was understood by nearly everyone. America and Germany had drifted toward conflict for months, and it seemed naturalif regrettablethat the nations would soon go to war.

President Wilson and his entourage departed the White House at 6:15 p.m. Not only was the president surrounded by US Army personnel but there were also sharpshooters placed in buildings along his route. On this evening, no chances were taken with the presidents security.

Arriving at the Capitol Building, President Wilson was brought inside and escorted to the chamber of the US House of Representatives. The chamber was the only room large enough to accommodate the members of the US House of Representatives and the US Senate, as well as the nine members of the US Supreme Court.

Entering the House chamber, President Wilson took heart from the outpouring of patriotic enthusiasm. Many senators and representatives waved American flags, and others shouted that they were willing to go to the battlefront themselves, if necessary. Removing his hat, President Wilson ascended the podium, adjusted his wire-rimmed spectacles, and began what he knew was the single most important speech of his career. Gentlemen of the Congress, Wilson began.