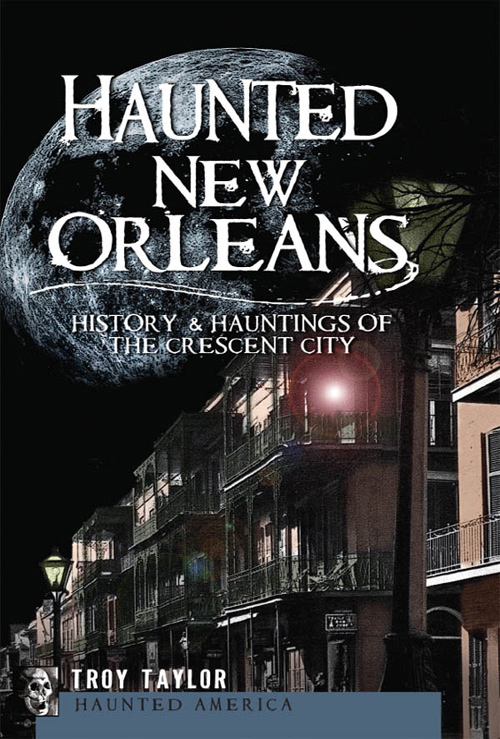

Published by Haunted America

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Troy Taylor

All rights reserved

First published 2010

Second printing 2011

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.259.9

Taylor, Troy.

Haunted New Orleans : history & hauntings of the Crescent City / Troy Taylor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-944-3

1. Haunted places--Louisiana--New Orleans. 2. Ghosts--Louisiana--New Orleans. I. Title.

BF1472.U6T397 2010

133.10976335--dc22

2010026637

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

INTRODUCTION

The very name New Orleans conjures up a succulent variety of thoughts in the mind of anyone who hears it: the soft sounds of jazz, whirring ceiling fans, wrought-iron gates and hot, spicy food. Along the swollen Mississippi River, the city dozes, only to come alive at night with the revelry of its people and the blare of music and laughter from Bourbon Street and the French Quarter.

These are the images of New Orleans that many people think of, but there is another side to the city as wellan underbelly and a darkness that is as carefully hidden as the gates to the small courtyards that lurk between buildings in the French Quarter. This dark side is there, just like the spectacular gardens and courtyards, but you have to know where to look for it. And if you dont see it at first, dont worry, because its liable to sneak up and surprise you when you least expect it.

The dark side of New Orleans is as much a part of the city as chicorylaced coffee and beignets and is filled with the seductive imagery of voodoo, murder and ghosts. Only in New Orleans could darkness and death seem so appealing.

New Orleans was established in the earliest days of the eighteenth century. The first colonists to stake a claim to the swampy lands were of French origin. They came to this hot and waterlogged place in the early 1700s, preceded only by explorers like LaSalle, who came down the Mississippi River in 1682 and claimed the land where the river ended for France. In 1699, two French Canadian explorers named Pierre le Moyne and Jean Baptiste le Moyne sailed in from the Caribbean and landed on a tiny bayou near the future site of the city. Since the Catholic holiday of Fat Tuesday fell on the next day, they called the spot Pointe du Mardi Gras.

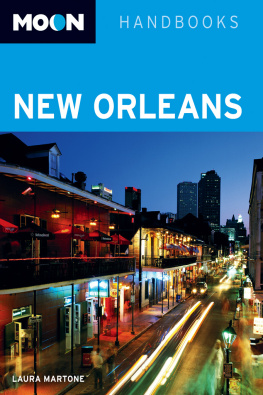

New Orleans mysterious and decadent French Quarter.

Exploring the New World was not all about adventureit was also about money. Colonies and exploration were expensive, and by 1700 the French were broke. The Bourbons of France were approached by a Scottish man named John Law, who created a New World company in which the French could invest and thereby settle the Lower Mississippi Valley. In reality, the plan was a scheme to bilk money from the investors in return for selling them Louisiana. Law was given a monopoly on trade, as well. Later, when it turned out that Laws company was merely a large confidence game, many of the settlers decided to ignore this and stay on.

During the first year of Laws operation, he decided that a town should be founded at a spot that could be reached from both Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River. In 1718, this town became La Nouvelle Orleans.

Development of the city began that year, but work was slow, thanks to brutal heat and the rising and falling waters of the Mississippi. There was talk of moving the city because of the danger of flooding, so levees were constructed, which spread out as the city and the plantations of the area grew. But rising water was not the only danger that could be found at the mouth of the Mississippi. In many early documents, writers spoke of the monsters that dwelt in the murky waters, and the Indian legends told of gigantic beasts that waited to spring upon unwary travelers. May God preserve us from the crocodiles! wrote Father Louis Hennepin.

Meanwhile, John Law was having problems holding up his end of the bargain that he made with the French. In order to get his money, he had promised his investors that he would have a colony of six thousand settlers and three thousand slaves by 1727. His problem, however, was a shortage of women. The colonys governor, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, wrote, The white men are running in the woods after the Indian girls. About 1720, one solution to cure the shortage of women arrived when the jails of Paris were emptied of prostitutes. The ladies of the evening were given a choice: serve their term in prison or become a colonist in Louisiana. Those who chose the New World quickly became the wives of the men most starved for female companionship.

The prisons also served as a source for male colonists. Many thieves, vagabonds, deserters and smugglers also chose to come to Louisiana to avoid prison time. They made for strange company when mixed with aristocrats, indicted for some wrongdoing or another, who also chose New Orleans over the Bastille.

New Orleans also lacked education and medical care. Despairing over the conditions, Governor Bienville coaxed the sisters of Ursuline to come from France and assist the new city. The first Ursulines arrived in 1727 and set to work caring for orphans, operating a school, setting up a free hospital and instructing slaves for baptism. They also provided a safe haven for the casket girls, young middle-class girls who had come in answer to the call for suitable wives. The young women were so named for either the distinctively shaped hats they wore or for the government-issued casket-shaped chests of clothes and linen they brought with them. No one can say where the name came from, but it stuck. The first of the casket girls arrived in 1728, and they continued to come until 1751, marrying those single male colonists who had been unable to snag one of the professional girls who had been sent from the Paris jails a few years before.

The Ursuline Convent on Chartres Street. The sisters set up the first free hospital in the city and the first schools. They also brought the casket girls to the citymiddle-class young women who made suitable wives for the settlers.