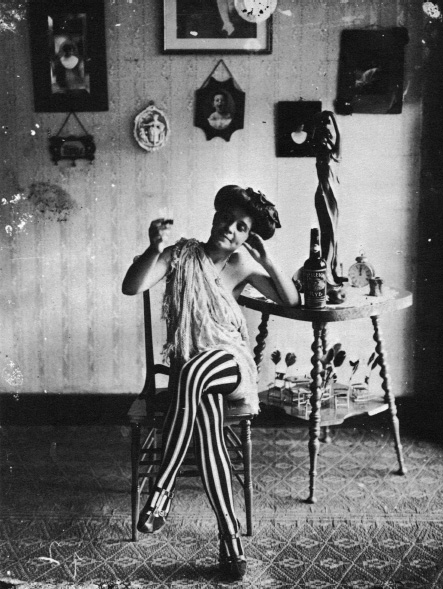

One of the women of New Orleanss Storyville. Photograph by Ernest Bellocq.

TROY TAYLOR

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Troy Taylor

All rights reserved

Unless otherwise noted, all images are from the authors collection.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.011.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Troy.

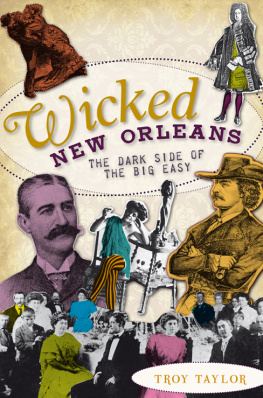

Wicked New Orleans : the dark side of the Big Easy / Troy Taylor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition: ISBN 978-1-59629-945-0

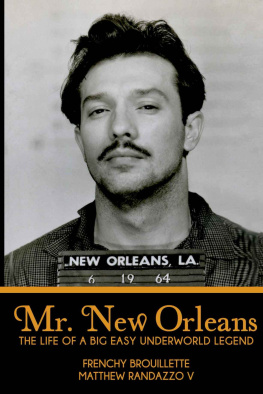

1. Crime--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 2. Criminals--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. 3. Organized crime--Louisiana--New Orleans--History. I. Title.

HV6795.N38T39 2010

364.10976335--dc22

2010018081

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T he author would like to thank the great chroniclers of crime and legend in New Orleans, including Lyle Saxon, Herbert Asbury, Robert Tallant and Edward Dreyer, along with many other writers and chroniclers of the citys life and death. Thanks also to the jazz musicians who created an American original and to Becky LeJeune at The History Press. As always, thanks to my wife, Haven, who makes it all worthwhile.

A CITY BORN IN SIN

N ew Orleans is a city that was literally born in sin. From the original charters that were based on fraud to the emptying of the French prisoners to provide settlers to the region, widespread government corruption, gaudy social functions, rampant prostitution and frequent lapses in any civilized moral code, New Orleans has a long and very colorful history of crime and vice.

The corrupt city of legend and tradition began during the days of French governor Marquis de Vaudreuil and continued through the years of the citys domination by Spain. It flourished between 1800 and 1803, when the province was neither French nor Spanish, and when a general sense of freedom allowed and encouraged the arrival of vagabonds and adventurers from all parts of the world. It the end, it would be as property of the United States that New Orleans would embark upon its golden age of crime and spectacular wickedness and would achieve its status as Americas leading city of sin.

In September 1717, John Laws Company of the West, popularly known as the Mississippi Company, obtained, by royal grant, control of the French province of Louisiana. At the time, there were almost no settlements in the region, which had long ago been claimed for France by the explorer LaSalle. The small outpost that existed nearby had a population of fewer than 300, consisting of a garrison of 124 soldiers, a few priests, 28 women and 25 children. The men were mostly adventurers and frontiersmen who had wandered into the province from Canada and Illinois, but the women, almost without exception, were deportees from the prisons and brothels of Paris. The hardships of life in the wilderness had not changed their manners and customs. When a worried priest suggested that sending away all of the immoral women would improve the culture of the province, Lamothe Cadillac, who was then governor of Louisiana, replied, If I send away all loose females, there will be no women left here at all, and this would not suit the views of the King or the inclinations of the people.

This was not the first time that a commercial enterprise had attempted to settle Louisiana. The Bourbons of France were broke by the early 1700s. They had spent vast amounts of money on exploration and now had vast lands under their control but not the money to actually develop them. When Scotsman John Law approached them with his grand scheme, he must have seemed like a godsend. The terms of the royal franchise issued to the Mississippi Company were granted to John Law with the understanding that he would import six thousand white settlers and three thousand slaves to the colony. They would then work, as a commercial enterprise, the gold and silver mines and pearl hatcheries with which the country was said to abound. The Mississippi Company was made up of investors and a board of directors, which elected Law the chief director and gave him almost unlimited powers. Under Laws plan, France would retain all governmental control of the new colony.

Laws authority over the enterprise allowed him to place himself and his representatives in almost every position of power in the colony. However, he did appoint Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, as the governor and commander of the region. Bienville had been in Louisiana for twenty years and, with his brother, Iberville, had played an important role in the early exploration of the area. He knew Louisiana well, and while he accepted his appointment to the governorship, he also suspected that Laws plan was an elaborate scheme. He had repeatedly told his superiors in Paris that there were no gold and silver mines in Louisiana and that the few pearls to be found in the Gulf of Mexico were worthless. He urged the French government to abandon its search for riches and focus instead on the development of agriculture in the rich lands of the Mississippi Valley. But his recommendations were dismissed because they provided too slow of a method of garnering the boundless wealth that the French were certain Louisiana had for them. Bienville accepted his position and, while suspicious of Law, hoped that he would soon have the authority to carry out the projects that he felt would truly develop the region.

John Law was a mathematical genius and one of the most flamboyant promoters in history. His grand scheme of the New Orleans colony was doomed to fail, and eventually, the French government ended his control over it.

Bienvilles commission arrived in February 1718, and soon after, he led twenty-five convicts, carpenters and a few adventurers from the Illinois country to a crescent-shaped bend in the river that he had surveyed nearly twenty years before as a good site for a settlement. In a cypress swamp that was teeming with snakes and alligators, he set his men to work clearing the forests and building sheds and barracks. He named the new settlement Nouvelle Orleans in honor of the French regent, the Duke of Orleans.

Work was soon underway, and Bienville sent the directors of the Mississippi Company glowing descriptions of the climate in New Orleans, the fertility of the soil and the many other advantages of the site he had chosen for the town. Other French officials, however, felt less optimistic about the site. They complained of the flat and swampy ground, the plague of crayfish, the frequent fogs, thick woods, clouds of mosquitoes and the fever-laden air.

Next page