All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House LLC,

a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Empire of sin : a story of sex, jazz, murder, and the battle for modern New Orleans / Gary Krist.

1. New Orleans (La.)History20th century. 2. Storyville (New Orleans, La.)History20th century. 3. New Orleans (La.)Social conditions20th century. 4. Storyville (New Orleans, La.)Social conditions20th century. 5. Anderson, Thomas Charles, 18581931. 6. CrimeLouisianaNew OrleansHistory20th century. 7. MurderLouisianaNew OrleansHistory20th century. 8. CorruptionLouisianaNew OrleansHistory20th century. 9. JazzSocial aspectsLouisianaNew OrleansHistory20th century. 10. Sex customsLouisianaNew OrleansHistory20th century. I. Title.

F379.N557K75 2014

976.335061dc23 2014003191

A UTHOR S N OTE

Empire of Sin is a work of nonfiction, adhering strictly to the historical record and incorporating no invented dialogue or other undocumented re-creations. Unless otherwise attributed, anything between quotation marks is either actual dialogue (as reported by a witness or in a newspaper) or else a citation from a memoir, book, letter, police report, court transcript, or other document, as cited in the endnotes. In some quotations I have, for claritys sake, corrected the original spelling, syntax, word order, or punctuation. Names and certain other nouns were often spelled in various ways in various sources (for example, axeman/axman); in these cases, Ive chosen the spelling that seems best or most plausible and used it consistently throughout the book, even in direct quotes.

It is no easy matter to go to heaven by way of New Orleans.

R EVEREND J. C HANDLER G REGG

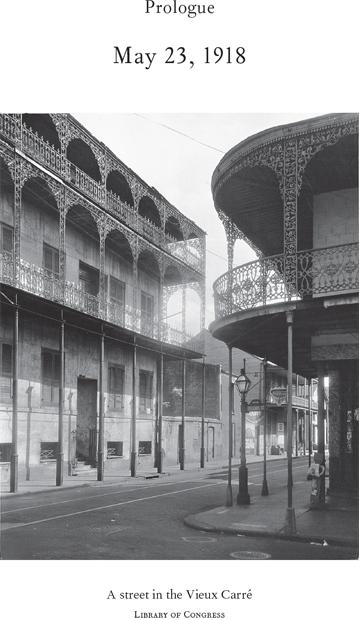

THE CRIME, AS DETECTIVES WOULD LATER TELL THE newspapers, was one of the most gruesome in the annals of the New Orleans police.

At five A.M. on the sultry morning of May 23, 1918, the bodies of Joseph and Catherine Maggio, Italian immigrants who ran a small grocery store in a remote section of the city, were found sprawled across the disordered bedroom of the living quarters behind their store. Both had been savagely attacked, apparently while they slept. Joseph Maggio lay face-up on the blood-sodden bed, his skull split by a deep, jagged gash several inches long; Catherine Maggio, her own skull nearly hewn in two, was stretched out on the floor beneath him. Each victims throat had been slashed with a sharp instrument.

A blood-smeared ax and shaving razorobviously the murder weaponshad been found on the floor nearby.

Police Superintendent Frank T. Mooney stood among the dozen or so detectives and patrolmen working over the grocery for clues. Summoned from his bed before dawn, the superintendent had immediately rushed out to the crime scene, located at the corner of Magnolia and Upperline Streets. It was a godforsaken neighborhood on the outskirts of Uptown New Orleans, a place where a few single-story pineboard shacks stood amid a sea of weed-choked empty lots. Until recent years, this area had been little more than a fetid swamp, populated by alligators and slender-necked herons. But now people actually lived hereItalians, mostly, along with an assortment of other recent immigrants and a few blacks too poor to live anywhere else. Like much of the part of New Orleans set far back from the river and its natural levee, it was an inadequate place for human habitation, a breeding ground for all kinds of disease and squalor. And now it had become a breeding ground for crime as well: street lighting was still unheard-of out here, and even the slightest rain could transform the low-lying, unpaved streets into stagnant rivers of muck, impossible for even the sturdiest of police vehicles to navigate.

Frank Mooney, forty-eight years old and still new to his job, understood that he had to oversee the investigation of this case very closely. It would be the first high-profile homicide of his tenure as police superintendent, and a crime so strange and sensational was bound to attract all kinds of unwanted publicity. In some ways, the case seemed straightforward enough. The intruder had clearly taken the Maggios own ax from the backyard shed and used it to chisel out a panel of the kitchen door and pry off the lock. He had then entered the kitchen, carried the ax down the short hallway to the bedroom, and used it, and perhaps the shaving razor, to butcher the sleeping Maggios. Hed apparently made no attempt to hide the murder weapons or otherwise obscure any evidence of the brutal crime that had occurred in that tiny, airless bedroom.

The question of motive, though, was more problematic. Robbery seemed the most obvious explanation, but there was little proof that anything had actually been taken from the house. True, the grocers bedside safe had been found open and empty. But there were no signs that the safe had been forced, and right beneath it sat a tin box, wrapped in a womans stocking, containing several hundred dollars worth of jewelry. Mooneys officers also found $100 in cash secreted under Joseph Maggios pillow. No professional thief could have overlooked such easy booty.

Chief of Detectives George Long, the experienced investigator whom Mooney had put in charge of the case, had a different theoryone that implicated Andrew Maggio, Josephs younger brother, who lived in the other half of the grocery building on Magnolia Street. Andrew had been the first person to discover the bodies, after allegedly hearing a scuffle in his brothers apartment and going next door to investigate. He was a barber by profession, and several days earlier had been seen taking a straight razor from his shop to have a nick honed from the blade. Based on this evidence alone, Andrew Maggioalong with another younger Maggio brotherhad been detained for questioning.

But there was one incongruous piece of evidence that seemed to exonerate the brothersand to point to another kind of perpetrator entirely: Shortly before noon, two detectives canvassing the neighborhood had stumbled across a clue just a block away from the murder scene. Right at the corner of Robertson and Upperline, scrawled across the planks of a wooden banquette (as sidewalks are called in New Orleans), theyd found a chalk message written in a crude, childish hand: