Dan would like to thank his mother, his sister, his children, the staff of the Innocence Project New Orleans and the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center, Morrison & Foerster, Ben Cohen, Clive Stafford Smith, Gary Wainwright, Justin Nobel, and UNO Press.

WHERE THEY ARE NOW

Karen Herman is now a judge in Orleans Criminal District Court, the same courthouse where she prosecuted Dan Bright's wrongful murder conviction.

Judge Dennis Waldron officially retired at the end of 2008 but has continued to fill vacancies at the court when needed. In early 2015, Orleans Criminal District Court Judge Frank Marullo was removed from the bench by the Louisiana Supreme Court after a probe by its investigative arm. The Supreme Court appointed Judge Dennis Waldron to sit ad-hoc, while the court continued its investigation.

Detective Arthur Kaufman was sentenced to six years in prison, in 2012, for his role in fabricating reports to cover up the New Orleans Police Department killing of two unarmed civilians, and the wounding of four others, in a shooting that took place on the Danziger Bridge, six days after Hurricane Katrina. In 2013, a U.S. District Court judge overruled the sentence, citing prosecutorial misconduct, and in 2015 that ruling was upheld.

Harry Connick retired as New Orleans District Attorney in 2003. My reputation is based on something other than a case, or two cases or five cases, or one interception or 20 interceptions, he told the Times-Picayune in 2012. Look at the rest of my record. I have more yards than anybody. As of 2016, at the age of 90, he still occasionally appeared at New Orleans nightclubs to sing, something he was known for.

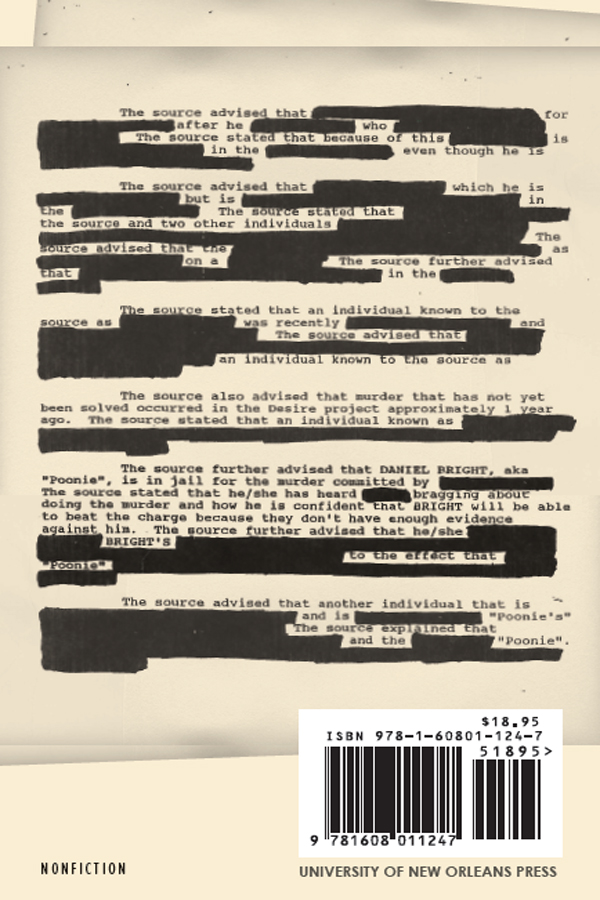

Len Davis remains in federal prison, though in 2012, during post-conviction trials in which Davis was representing himself, attorneys acting as standby counsel filed motions to vacate his convictions and sentence. Their argument was that Davis has a serious mental impairment that renders him incompetent to stand trial.

Ben Cohen presently lives with his family in Cleveland, Ohio, though he still works with the New Orleans-based legal group, The Promise of Justice Initiative, and continues to represent New Orleans death row cases. As of 2016, he was working on, among other issues, the case of Corey Williams, who was sentenced to death at age 16 for a crime he did not commit. In 2015, Cohen received the Sam Dalton Capital Defense Advocacy Award, handed out by the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Clive Stafford Smith now represents detainees being held at Guantanamo Bay and is the director of Reprieve, a legal organization that provides, free legal and investigative support toBritish, European and other nationals facing execution, and those victimised by states abusive counter-terror policies. In 2005, Smith was awarded the Gandhi International Peace Award. In 2010, he received the International Bar Association's Human Rights Award.

Kathleen Hawk Norman passed away in her sleep on April 15, 2009. She was fifty-four.

CHAPTER ONE

THE CITY EXPLAINED

I came up in the Florida Projects during the 1970s and 1980s, one of the most violent times in the history of New Orleans. Florida was a bunch of three story brick buildings developed for whites after World War II. Initially, black people weren't allowed in. Then the blacks moved in, and the government let the projects fall apart. You could see that at one time it was a nice place to live, but no more. Florida was one of the most violent projects in the city and the poorest. The pool was broke, the swings were broke, and there was bottle glass broken all over the playground. Everything a kid needed to enjoy himself didn't work. No flowers, no trees, just dirt and concrete. People walking around with no shoes on their feet, people going without eating, no heat, no water, the lights go out and it's cold, guys selling drugs, shootings, drinking, prostitution. Every time you hear gunshots, you gotta lay on the floor. It's a routine your parents teach you at a young age. I remember going to school one morning when I was real young, and there being a dead body in the stairwell. A man had been shot in the head. That wasn't a big deal. All you do is walk over it, go on to school, mind your own business.

When I got in a car and went uptown, on St. Charles Street or around the lakefront, I would see everyone living totally different. Kids driving around in nice sports cars their parents bought for them. I remember one kid's parents bought him a Camaro T-top with shiny rims. He played football, if I'm not mistaken. All the girls loved him, loved his material things, and they'd follow him around. Guys like this would drive over to their girl's house, pick them up, go play tennis. Yeah, I thought I could get along with them. But later on, the more I got to know these kids, the more I realized that they took everything for granted. I would just look at them and think, you all have no idea what is going on in this world, and you know nothing about New Orleans. In New Orleans, everyday someone is killed. And the only time they would know that is if their parents watched the news.

When we were young, my pops used to take me and my little brother and sister to see Al Copeland's house, the man who started Popeye's Chicken. He was a big celebrity around New Orleans, and every Christmas he lit his house up with all sorts of lights. It was so perfect, lights everywhere, reindeer, Santa Clauses. My brother and sister were overwhelmed by the lights, but I wasn't excited about that. I was trying to figure out how I can get a house like that, screw those lights. Maybe that is where it started, I don't know. I wanted that success. I wanted that power. New Orleans is like crabs in a bucket, everyone is trying to make it out. Everyone is trying to get something, and no one is going to let someone else take anything from them. I had two parents, I had clothes on my back but I wanted another life. I enjoyed the street life. I wanted to do what the old gangsters were doing, but do it better. I wouldn't say it was forced on me, but I grew up in it, and I was good at it.

My two best friends were Lucky and Romeo. Lucky was short and stocky, like a bulldog, and very intelligent. He was a bookworm like me and always walking around with a little book in his pocket. People picked on Lucky, and he fought back with his mind. Hey ugly-ass, someone would say, and Lucky would reply, Bet I can spell better than you! In the Projects, Lucky lived directly below me. I'd knock on the floor with a broomstick to get his attention, and we'd meet outside. Romeo lived across the way. He was tall and slim, one of those pretty boy types. Romeo wasn't that educated book-wise, but streetwise he was. He came up poor, maybe six brothers, six sisters. Romeo was Creole. His people were from Lafayette. Me and Lucky used to go by his house to get him, and we'd hear his mother and father talking in French. I wanted to learn it, but he never wanted us to hear that. Romeo pretended he wasn't Creole. He liked to be black. They were the only two people in the city I truly trusted.

They were also my business partners. At elementary school, you had kids from the Projects, like us, and then you had house boys. They lived in houses in the Lower 9th Ward, on the other side of the Industrial Canal. House boys weren't rich, but they were richer than us, and they came to school with candy. Now and Laters, Snickers bars, M & Ms, this candy called Whatchamacallit. They gave it to us because they wanted to be in our little group, then we sold it back to them. Later we started selling cigarettes, a dime a piece. Our spot was behind the school. A few other guys tried selling there, but we let them know it was our thing. We wouldn't let anyone else sell nothing, uh-uh, we weren't gonna let them profit off what we started. If guys tried, we jumped them. It didn't matter if they were older than us. We used sticks, whatever we could get our hands on. From an early age I knew, you had to control the market.